In his Poetics, Aristotle was likely to have been the first critic to formally outline the structure and guiding principles by which fifth-century BC Greek dramatists had to abide.

Aristotle stated that drama, especially tragedies, should have one action (a plague, a mysterious murder, a war, a national crisis), a hero of great stature (a king, prince or person of noble birth with a tragic flaw such as pride, arrogance, ambition, short temper), events that must unravel and come to a resolution within the span of 24 hours, and a hero who, because of human frailty, moves from good to bad.

Ultimately, the hero’s tragic flaw, an infirmity often supplanted by the gods, visits calamity on the hero, his loved ones, and the nation.

William Shakespeare adhered to most Aristotelian dramatic tenets, weaving in subplots by giving his audiences gut-wrenching bloody scenes where knives sink deep, heads roll, eyes are gouged, court intrigue runs rampant, and characters are dispatched in twos, threes, and fours. The aforementioned were enacted, much to the delight of Elizabethan audiences, on the stage, in full gruesome narrative and gory visual depictions. He added minor scenes for comic relief and stretched his plays’ plots and actions over days, weeks, months, and years.

Act I, Scene I of Shakespeare’s King Lear is among the best dramatic strokes of genius. With an economy of dialogue and action, its fast-paced exposition foretells the doddering king’s weakened judgment, petulant temperament, and propensity for making impulsively rash and unwise decisions that backfire on him.

Having ruled England for a while, Lear is ready to give up his throne and slide into retirement. Much like Donald Trump’s staged and choreographed official briefings and public campaign orations, Lear invites his daughters Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia to hear his important announcement. The older daughters’ husbands are in attendance; Cordelia, the youngest, is attended by two suitors vying for her hand.

Lear decides to stage his courtly deliberations as a grand retirement spectacle replete with self-serving aggrandizement. With no male heir to succeed him to the throne, and because he’s had his way for a long time, Lear invites courtiers, earls, dukes, knights, and foreign dignitaries to witness the disposition of his kingdom, a conditional bequeathing of large real estate holdings (but, as is later revealed, not the power of the throne) to his daughters.

Lear’s announcement comes with strings attached: Each of the daughters must publicly declare the extent of her love for him. Competing with each other and aware of their father’s need for glorification and adulation, Goneril and Regan spew sappy sophomoric bromides about the extent of their love.

Regan out-performs her older sister’s inflated fibs with exaggerated expressions of love. Not only does she overstate the intensity of her adoration, but she also, much to Lear’s pleasure, outdoes her sister with boot-licking flattery.

Self-centered Lear is incapable of seeing through the spurious fabrications and inflated self-serving lies. He points to a map and draws demarcation lines allotting two-thirds of his kingdom to the two older daughters.

His ego boosted, Lear invites Cordelia, his youngest and dearest daughter, to declare her love for him. Expecting Cordelia’s platitudes to dwarf her sister’s feigned remarks, Lear is shocked at her brief yet sincere response: Nothing, my Lord. Unhappy that I am, I cannot heave/ My heart into my mouth. I love your majesty/According to my bond; no more, no less.

To which impetuous Lear angrily responds: “Nothing begets you nothing,” and bestows one-half of Cordelia’s inheritance to each of her two older sisters, then tells the king of France, one of two suitors, he could have her without a dowry, to which the king responds: “She is herself a dowry,” an assertion that comes to fruition in the last two acts.

Trustworthy Cordelia is banished from the kingdom.

Perhaps because of a diminishing mental capacity, Act I, Scene I succinctly exposes Lear’s love for spectacle, pageantry, pettiness, petulance, impetuousness, impulsiveness, vengefulness, retribution, and rashness in making viscerally emotional instead of rational decisions.

Beginning in 2004, Donald Trump hosted The Apprentice television show and pretended to be the program’s playwright, director, stage manager, choreographer, set designer, and protagonist. Through 2015 he treated the participants as antagonists to be harangued, insulted, and humiliated.

No doubt Trump honed his acting, communication, hectoring, self-aggrandizing, manipulative, and self-serving skills into an art form during those years.

Having never watched this show, the only thing I remember were brief station adverts portraying a ruddy-faced man whose hairdo glistened with an unnatural orange tint. Serving as judge, jury, and executioner, he pointed a stubby finger at cowering victims and pronounced his verdict: “You’re fired,” a phrase he would later ejaculate in campaign speeches, to the delight of adoring supporters.

Having mastered the art of manipulating audiences, Donald Trump took his dark magic show on the campaign trail. Using every trick in his inventory of lies, manipulation of facts, and personal attacks on the 2016 Republican presidential candidates, Barack Obama, the liberal left, and the media, Trump introduced a new low in American politics.

That Marco Rubio, Ted Cruz, and Lindsey Graham have sidled up to Trump after having been brutally attacked and denigrated throughout the 2016 presidential campaign is a telling comment.

Since January 2017, Donald Trump has refined his manipulation of public discourse into an art form by utilizing meetings with foreign dignitaries at the White House and abroad, a readily available army of reporters on the White House lawn as he is about to embark on a Marine One excursion to a rally, a golf course, or Mar-a-Lago, his campaign speeches, especially in red states, and, since the covid-19 virus has become a pandemic, his almost daily White House briefings.

During these sessions a multitude of journalists pounce on each other to ask questions. Ever the impresario, Trump seems to thrive on the barrage, often choosing a friendly plant whose question allows him to pounce on one of his many pet peeves. Often an unfriendly question is thrown his way to which he responds with disdain, attacks the reporter, and accuses the “leftist, socialist, liberal fake news” of bias and distortion.

The second venue deals with his overseas trips to G20 and other international conferences and events where, should he not get his way (or should other world leaders outshine him), Trump sulks, spews some bromides (“everybody is taking advantage of us”), and plays the schoolyard bully by taking his marbles and heading home.

Since his election in November 2016, Donald Trump has crisscrossed the country to stage campaign speeches to supportive Make America Great audiences. By not following a script, Trump moves from one fabrication and insult to the next, inviting his audiences to repeat a refrain, jeer at a victim du jour, and portrays himself as a victim of hoaxes and fake media.

Restricted by covid-19 from traveling to campaign speeches and having impromptu press conferences on the White House lawn, Donald Trump and his handlers have resorted to a controlled format to help keep his image and message in perpetual public view.

Staged White House briefings choreographed to help Trump appear presidential are held almost daily.

In addition to the permanent props (Mike Pence, Dr. Anthony Fauci, Dr. Deborah Birx), each day a new set is paraded. These include health experts, government officials, Trump staff members, businessmen, and Cabinet members. Having been introduced by stage manager Trump, each of the above, on cue, launches a laudatory statement or two about the president’s leadership and his outstanding job performance as he nods approvingly.

How Lear-like has Donald Trump become.

Like Shakespeare’s character, Trump is quick to fire an underling—always in the wee hours of the morning with a tweet. A secretary of state, national security adviser, inspectors general (thus stripping oversight powers), a Navy captain (maligned as “stupid” and “naive” for having the moral fortitude to protect his men), Environmental Protection Agency personnel, and whistle-blowers daring to tell the truth about Trump’s mismanagement of relief efforts.

During each of the briefings Trump blames his predecessors, especially Obama, for shortcomings. He is more concerned about the economy than citizens’ health; he sends needed medical equipment to red states, especially those whose Republican governors laud his efforts; he punishes those who criticize him by withholding medical supplies. And despite the fact that there is a shortage of masks in the U.S., he sent 1 million masks to Israel.

Frustrated, angry, and humiliated at having been denied stopover visits and brief domicile in Regan and Goneril’s castles, Lear, furious and physically and emotionally unhinged, loses touch with reality and becomes a deranged vagabond.

It seems to me that Donald Trump’s April 13 assertion that “When somebody is president of the United States, the authority is total” is a sign that ill-advised and egregious decisions of the last three months during which covid-19 has exploded are catching up with him—mentally, physically, and emotionally. He is short-tempered, lashes out at friend and foe, is erratic, self-absorbed, and preoccupied with his re-election.

Lear could be forgiven for the unraveling of his character due to the onset of a second childhood and his desire to free himself of responsibility, to relive his younger days, and to squeeze a carefree existence for his remaining days.

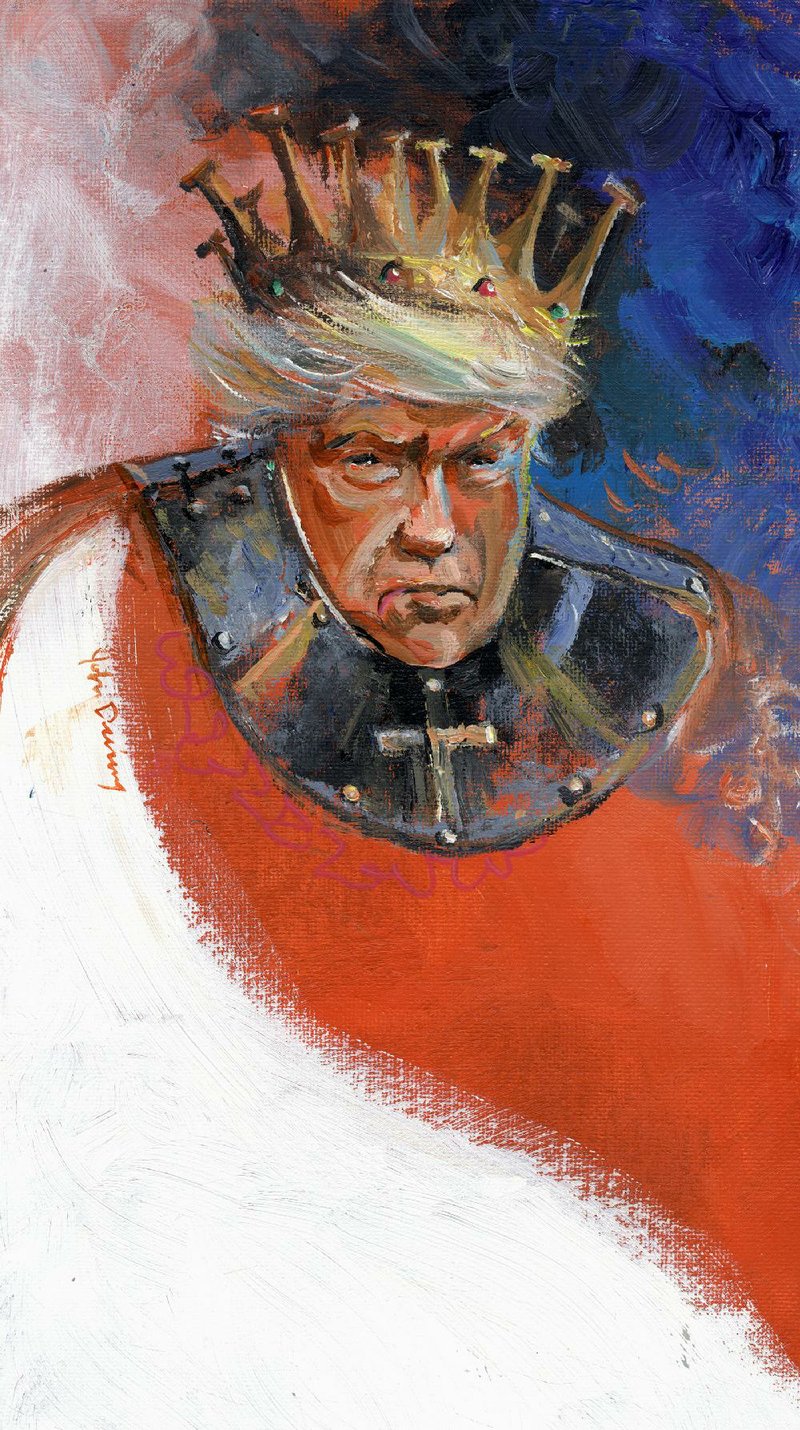

I wonder what Shakespeare would have thought of Donald Trump, and how he would have depicted him in a coronavirus-themed pandemic tragedy. I doubt that Lear would be a prototype. Instead, the English bard would have created a composite character, a flawed amalgamation of an Iago, Claudius, Lady Macbeth and her weakling husband, Shylock, Richard III, and John Webster’s Bosola from his tragedy The Duchess of Malfi.

Three heroes will no doubt stand above all others: Gov. Andrew Cuomo, Dr. Fauci, and Dr. Birx who, even as they are exploited as briefing props, have exhibited integrity, altruism, and professionalism.

Only time will tell whether an angry, frustrated, and unhinged Donald Trump will point his stubby finger and tell them, “You’re fired!”

Raouf J. Halaby is a Professor Emeritus of English and Art. He is a writer, photographer, sculptor, an avid gardener, and a peace activist. A version of this guest column appeared in Counterpunch.