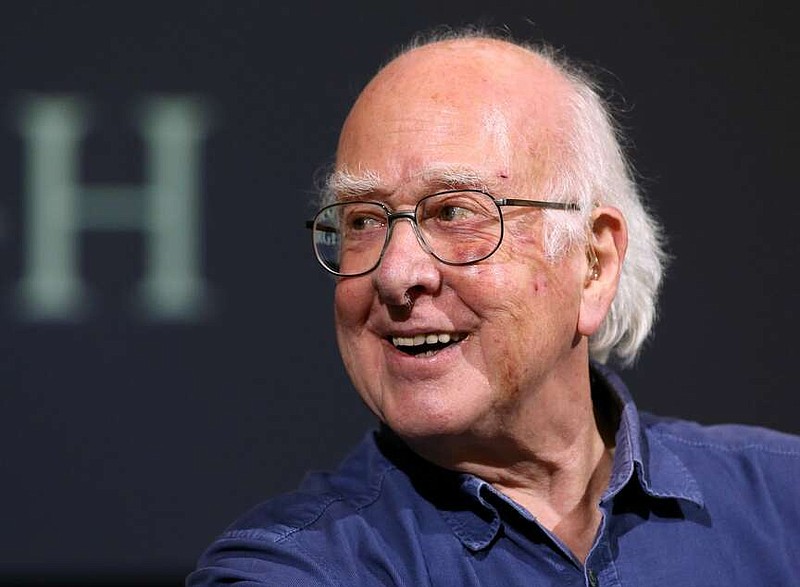

LONDON -- Nobel prize-winning physicist Peter Higgs, who proposed the existence of the so-called "God particle" that helped explain how matter formed after the Big Bang, has died at age 94, the University of Edinburgh said Tuesday.

The university, where Higgs was emeritus professor, said he died Monday following a short illness.

Higgs predicted the existence of a new particle, which came to be known as the Higgs boson, in 1964. He theorized that there must be a sub-atomic particle of certain dimension that would explain how other particles -- and therefore all the stars and planets in the universe -- acquired mass. Without something like this particle, the set of equations physicists use to describe the world, known as the standard model, would not hold together.

Higgs' work helps scientists understand of the most fundamental riddles of the universe: how the Big Bang created something out of nothing 13.8 billion years ago.

Without mass from the Higgs, particles could not clump together into the matter humans interact with every day. But it would be almost 50 years before the particle's existence could be confirmed.

In 2012, in one of the biggest breakthroughs in physics in decades, scientists at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, announced that they had finally found a Higgs boson using the Large Hardron Collider, the $10 billion atom smasher in a 17-mile tunnel under the Swiss-French border.

The collider was designed in large part to find Higgs' particle. It produces collisions with extraordinarily high energies in order to mimic some of the conditions that were present in the trillionths of seconds after the Big Bang.

Higgs won the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work, alongside Francois Englert of Belgium, who independently came up with the same theory.

Edinburgh University Vice Chancellor Peter Mathieson said Higgs was "a remarkable individual -- a truly gifted scientist whose vision and imagination have enriched our knowledge of the world that surrounds us."

Born May 29, 1929, in Newcastle, northeast England, Higgs studied at King's College, University of London, and was awarded a PhD in 1954. He spent much of his career at Edinburgh, becoming the Personal Chair of Theoretical Physics at the Scottish university in 1980. He retired in 1996.

One highlight of Higgs' career came the 2013 presentation at CERN in Geneva where scientists presented based on statistical analysis that the boson has been confirmed.

"There was an emotion -- a kind of vibration -- going around in the auditorium," Fabiola Gianotti, the CERN director-general told The Associated Press. "That was just a unique moment, a unique experience in a professional life."

Gianotti recalled how Higgs often bristled at the term "God particle" for his discovery: "I don't think he liked this kind of definition," she said. "It was not in his style."