What does home look like for you? Are there objects that may not be worth much money but are highly valued all the same? What parts of history influenced you that others may not know about?

Those were some of the things on Samantha Sigmon's mind as she began to piece together "Ozark Home, Beyond the Frame," an exhibit of contemporary art and items from family life in the area. Sigmon organized the show with other Northwest Arkansas natives Cory Perry, Deena R. Owens and Dana Holroyd.

The "Ozark Home" exhibit is split up into two sections, both of which will be shown in Springdale, one at The Medium at 214 S. Main St. and the other at the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History, 118 W. Johnson Ave. It will open to the public May 13, starting with a reception at Shiloh Museum from 3-5 p.m.

While growing up in Fayetteville, Sigmon's idea of art and valued objects was filtered through a different kind of lens than she has now.

"I grew up before there was a Crystal Bridges; I didn't go to a lot of museums," Sigmon says while walking through the gallery at The Medium. "For me, my dad was a brick mason, and we had these things from my grandparents, these photos that we passed down, and that was where the value was."

Sigmon attended school for art and art organizing and has enjoyed a career in the arts, working for local art venues like Fayetteville Underground and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, opportunities across the country, like some in Los Angeles and Virginia, and many others since. She recently moved to Maine for a new gig.

As she gained experience handling art in big cities, the objects and determining their value were very different. Things were more expensive, and there wasn't always a connection from the gallery to the artist. "Ozark Home" was an chance for her to balance the two swings of that pendulum.

"This is me trying to grapple with growing up here and caring a lot about art and art organizing and putting those things together," she says. "The craft part with the contemporary art of the time."

Because of the great variety of backgrounds that the artists come from, the result is an eclectic mix revealing the lesser known parts of the Ozarks of the past, such as Black history and queer history.

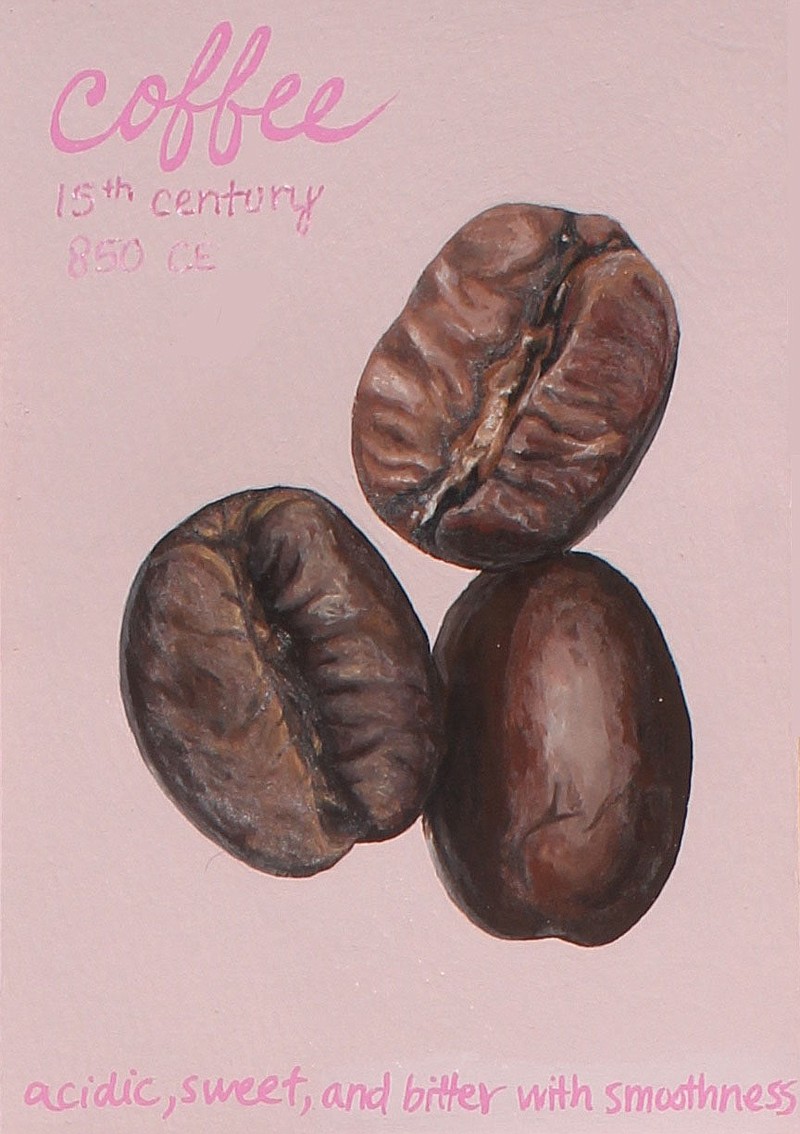

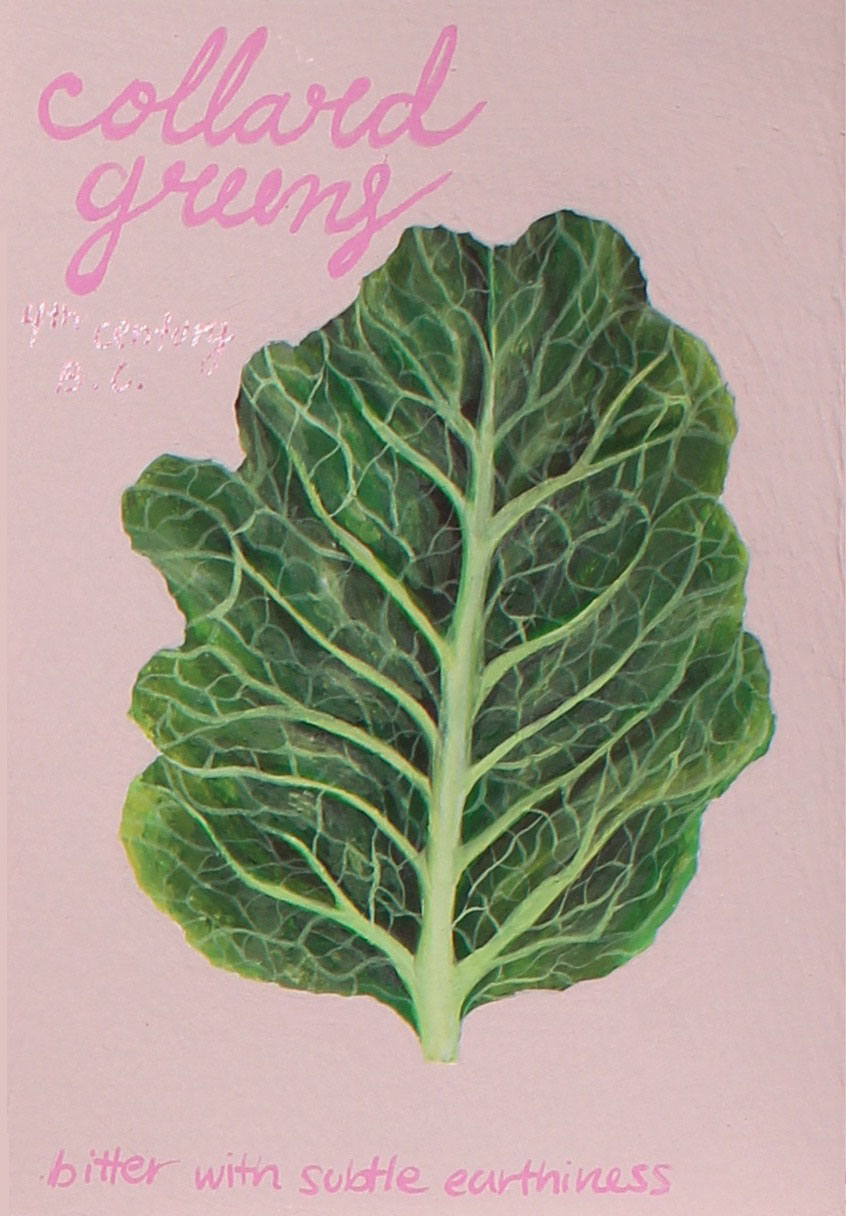

Madison Moon's works are small, rectangular gouache paintings of foods with a pink background. They're all foods that have helped Black people survive, Sigmon says. Through nine examples, Moon shows the viewer things that they may not have realized came from Black communities and helped them and others thrive.

"They might have a contested history, like with coffee and black-eyed peas," Sigmon says. "They're standards of Southern cooking that came from the Black community. They're beautiful and sweet, with inscribing underneath, and it's knowledgeable at the same time."

Moon says they created the paintings to showcase erased or unknown origins of the foods in a historic or even scientific-looking style. They originally got the idea when asked to participate in another exhibit organized by Cory Perry as a part of Juneteenth.

"Food was the first thing that came to mind when I thought of survival in the African American community and how it played a significant role," Moon says. "I created these paintings as a way to honor my ancestors and their legacy, through thankfulness and recognizing their erasure in America.

"As a Black person, when I eat these foods, I feel comfort, pride and closeness to my ancestors, because I know these foods provided them similar, if not the same, feelings."

Moon says they hope the paintings will remind others to be mindful of how they partake in food and other elements of Black culture, as well as its origins.

Walking in to view "Ozark Home," you might notice right away that there are a number of tables of various sizes and chairs. That wasn't something Sigmon was looking for outright, but it found its way into a number of the artists' works.

A knotted hickory table sits front and center with a book of drawings open on it next to jars of dried items that Sigmon says the artists and MFA students Danny R.W. Baskin and Lee Byers are looking forward to eating or adding to meals once the show is done.

Baskin made the table, while Lee did the tabletop's arrangement. It will be their dining table once the exhibit comes down.

"They were doing a lot of contemporary art world things ... then the pandemic happened, and they became so much more about domestic space and making everything for themselves and their friends," Sigmon says. The pair got chickens, started making ceramics and sourcing their own food. "That change from contemporary to use and craft while still being creative in life" is what interested her about it.

In front of Kim Lý's 6-by-6-foot colorful canvas collage are two red stools that invite the viewer to sit and take in the work that includes portraits of her Vietnamese family members taken on a night of celebration. It was her first trip back to Vietnam in nine years and coincided with Lunar New Year.

Sigmon says she is excited to have this particular one on display because Lý doesn't show her works all that often. She appreciates Lý's perspective as someone who grew up in Fort Smith, but most of her family is in Vietnam. She seeks to represent her own lived experience through transnationality, of people who feel like they belong in more than one place or culture simultaneously.

A 3D printed red stool stands on a multicolored shelf in between the two life-size stools, symbolism for the communal experience.

"This pivotal piece of furniture is often seen on the streets of Vietnam and in people's homes, where guests are invited to eat," Lý says by email.

"In this space that I've created, I invite you to sit with my family; my home," her artwork label reads. "The tales of Vietnamese refugees and their community in Fort Smith are not included when one looks up 'Ozark culture,' but in the late 1970s, Fort Chaffee was a temporary home to over 50,000 Vietnamese refugees who came to Fort Smith, many of whom chose to stay. 'Return Home' asks, 'Where do these stories exist in the larger picture of the Ozarks?'"

To Lý, home resides in a space not marked by physical borders or territory.

"I don't feel that I'm from the Ozarks, and I don't feel that I'm from Vietnam," she says.

Amber Imrie, by contrast, grew up in what Sigmon calls a back-to-the-lander family, where most of their time was spent outdoors. They were rasied off the grid, an unconventional upbringing that didn't include public school, electricity or running water.

"My childhood experience of living in the Ozarks was embedded in poverty and rural environment," Imrie says by voice message. "I pull from the magic ... and the horror of those places when I'm making my work. All the projects I'm really drawn to ... show this duality of home being a place of nostalgia and safety and also a place that could be very terrifying."

That's often what Imrie is trying to get to in their work, leaving space for comfort as well as questioning it; imagery that could be seen as grotesque but when it's paired with something familiar, "What does that bring up?"

Imrie's "Above Ground" is one of their brand new works, a collaged, hand-stitched collection of two photos coming together on quilt batting. Sigmon is amazed how Imrie will sit on the ground stitching the item right before it gets placed on the wall.

"A lot of their works are about growing up alternately, but also thinking about gender and gender identity in Arkansas," Sigmon says. "There's a lot of that topic throughout this, growing up in the country and feeling constrained by a binary, so 'How do you do that?' and 'How do you make work about that?'"

"Above Ground" features images of an above-ground pool in a rural home setting. The title refers to both the above-ground pool and images of the forest floor.

"A pool is something very fancy and middle class to have if it's in the ground, but if it's above ground, it's seen as being white trash," Imrie says. "I wanted to point to that as a class distinction, but the piece interweaves the natural ground surfaces of the Ozarks."

They're "micro images of life in all of its complexity happening around you and how they're embedded in our natural spaces."