We all have our articles of faith.

Some people believe in the quasi-sacredness of guns, that they are more often the solution than the problem and, besides, like the poor, they will be with us always and forever.

And other people — like me — believe that the artifacts of our culture — movies, cable shout shows, pop songs — may be symptoms of a sick culture, but not the cause.

I believe this because I want to, because I am entertained by dark stories and murder ballads. Because I would not take it upon myself to deny any artist the expression of their ideas or dictate what form this expression should take. And because the free market is governor enough on the excessive appetites of would-be artists. Shock draws a crowd, but unless it's underpinned by some quality of grace — unless it tells us something about who we are and how we got here — it dissipates quickly and is forgotten.

Good art lasts, and that which is cheap and tawdry and anti-human doesn't, though it might create a sensation for a while. That's my faith.

But think of how many murders you've seen committed in your lifetime. According to a 2020 report by the American Psychological Association, the average American child will witness 200,000 violent acts on television before age 18. A lot of this — 46% — is cartoon violence, which we might think shouldn't count. After all, Wile E. Coyote is remarkably resilient and seems to suffer no effects that hold over from scene to scene.

But that's part of the problem, some health-care professionals argue. Cartoons, they point out, are more likely to juxtapose violence with humor and less likely to show the long-term consequences of violence than live-action programs. While there are those who argue that cartoon violence doesn't have the same effect on children as "real" apprehended violence, some studies have shown exposure to violent cartoons increases the likelihood of aggressive antisocial behavior in youth.

And television, once the prevailing form of media and entertainment in the United States, is now just part of an ever-evolving media landscape that includes video games, music and movies. And while broadcast television adhered to a set of standards of practices intended to carve out a sanitized zone for family appropriate viewing, in truth the censors concentrated more on eliding sex and profanity than shielding children from violence. Similarly, there's no significant difference in the level of violence in PG-13 and R-rated films.

And nearly all American teenagers are involved in video games to some extent; according to a 2020 study by the Pew Research Center, 97% of teenage boys and 83% of teenage girls regularly play video games.

A 2012 study found that 80% of teens played at least three hours a week on a game console (as opposed to more casual gaming on a mobile device). That same decade-old study found that 25% of teens played 11 hours or more per week. In 2017, almost as many teenagers identified themselves as fans of competitive video gaming — esports — as identified themselves as professional football fans.

Tipper Gore and her Parents Resource Music Center raised alarms about violent, drug-related or sexual themes in pop music in the '80s; I think their campaign was misguided and counter-productive to their cause.

What I want to believe is that the overwhelming majority of people can and will recognize the world for what it is, a dangerous and potentially unhappy place where bad things sometimes happen to innocents and no one is guaranteed a safe ride home. And that we can somehow accommodate ourselves to that world, and find or at least pursue happiness, and differentiate between the kind of drama that's played out on shows like "Ozark" and "Better Call Saul" and our less intense reality, and calibrate our behavior accordingly.

Shakespeare is worth the blood. Quentin Tarantino is worth the blood. But I do not know that I'm right about that.

Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge, Warren Clarke as Dim, James Marcus as Georgie and Michael Tarn as Pete in “A Clockwork Orange.”

Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge, Warren Clarke as Dim, James Marcus as Georgie and Michael Tarn as Pete in “A Clockwork Orange.”

'A CLOCKWORK ORANGE'

When Pauline Kael reviewed Stanley Kubrick's "A Clockwork Orange" in 1971 she wrote:

"At the movies, we are gradually being conditioned to accept violence as a sensual pleasure. The directors used to say they were showing us its real face and how ugly it was in order to sensitize us to its horrors. You don't have to be very keen to see that they are now in fact desensitizing us. They are saying that everyone is brutal, and the heroes must be as brutal as the villains or they turn into fools ...

"There seems to be an assumption that if you're offended by movie brutality, you are somehow playing into the hands of the people who want censorship. But this would deny those of us who don't believe in censorship the use of the only counterbalance: the freedom of the press to say that there's anything conceivably damaging in these films — the freedom to analyze their implications.

"If we don't use this critical freedom, we are implicitly saying that no brutality is too much for us — that only squares and people who believe in censorship are concerned with brutality ...

"Actually, those who believe in censorship are primarily concerned with sex, and they generally worry about violence only when it's eroticized. This means that practically no one raises the issue of the possible cumulative effects of movie brutality.

"Yet surely, when night after night, atrocities are served up to us as entertainment, it's worth some anxiety. We become clockwork oranges if we accept all this pop culture without asking what's in it. How can people go on talking about the dazzling brilliance of movies and not notice that the directors are sucking up to the thugs in the audience?"

Kael — who went on to call the film "pornographic" — wasn't alone among critics dubious about "A Clockwork Orange;" initially the film received mixed reviews and was even pulled from British theaters (at the behest of Kubrick) after incidents in which young Englishmen committed crimes allegedly inspired by the antics of Alex (Malcolm McDowell) and his Droogs.

But it has endured, and most people would now receive it as a darkly funny dystopian nightmare that was prescient in its critique of psychotherapy. Some would perceive in its disaffected youth gangs and "progress" from regular to what Alex insists is "ultra-violence" a sophisticated fable about the ultimate victory of mechanization and dehumanization as the disturbed, cruel but vitally human Alex is eventually turned into "a clockwork orange" — a robot, an obedient, mechanical citizen — through the tortures of therapy.

Which is to say, I don't agree with Kael that the movie is pornographic. I think it is troubling and truthful. I think it is an argument worth making, and worth considering.

I don't think Kubrick was sucking up to the thugs. But there are movies — and TV shows, video games and pop songs — that do exactly that.

The only answer to bad art is to not pay undue attention to it, not because it is unwholesome but because it (generally) isn't to my taste. For most of those who are self-aware enough to read think-pieces in newspapers about violence in the media, the self-regulation is enough. We like what we like and trust that what we like is "good" while allowing ourselves some "guilty pleasure" exceptions.

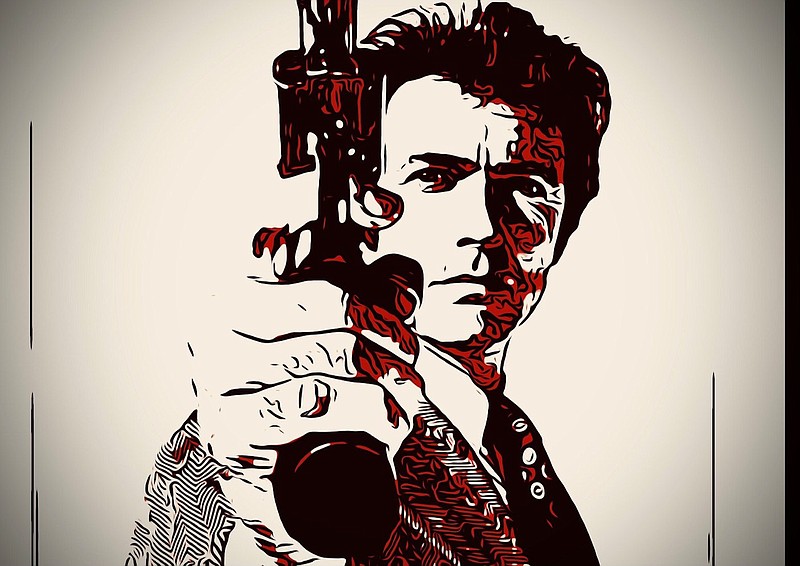

We might enjoy "Dirty Harry" (I did; Pauline Kael did not) or something like John Carpenter's "Assault on Precinct 13," without taking it very seriously. Sam Peckinpah's "Straw Dogs" might upset us, particularly the 30-minute finale in which the committed cerebral pacifist played by Dustin Hoffman coolly and calculatedly kills the men who have violated his home and made of him a cuckold.

"A Clockwork Orange," "Dirty Harry" and "Straw Dogs" were all released within a few months of each other in 1971. Are they toxic? Some would hold so, but maybe they are also a kind of inoculating bacteria, like the germs and micro-organisms kids used to get from playing in the dirt. Maybe they help build up some sort of healthy immunity to the deleterious effects of consuming violence.

AN EROTIC FASCINATION

But let's not kid ourselves.

I have always argued that the greater part of America's problem with guns is not the quandary some perceive is presented by the Second Amendment, but the erotic fascination so many seem to have with weaponry. And part of that erotic fascination stems from the iconic roles guns have played in our entertainments.

Life imitates art: We know James Bond's Walther PPK (Daniel Craig upsized to a Walther P99) and Harry Callahan's Smith & Wesson Model 29. In 2009, an aspiring rapper and scam artist named Raymond "Ready" Martinez lost a gun battle (and his life) to police when his Mac-10 jammed when he fired it while holding it parallel to the ground, like the armed robbers in the opening scene of 1993 Hughes Brothers movie "Menace II Society."

The Hughes Brothers had their actors hold their guns sideways because it was easier to get an unobstructed shot of the actor's face that way.

The movies teach us how to act, how to flirt, how to smoke cigarettes, how to dress, how to carry ourselves. It's not inconceivable to think that other people learned other things from them. The Army uses video games to train soldiers; it's not hard to see the correlation between playing a first-person shooter game and piloting a drone. (The movies have certainly noticed; see the 2021 Netflix film "Outside the Wire," 2014's "Good Kill" and 2015's "Eye in the Sky.")

In 1995, three years before the Westside School shooting in Jonesboro and four years before the mass shootings at Columbine, Dave Grossman, then a U.S. Army lieutenant colonel serving as professor of military science at Arkansas State University in Jonesboro, told me he believed the country was in denial over the extraordinarily harmful nature of consuming violence as entertainment.

Grossman had just published his book "On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society," a work that's now considered a prime text; it's required reading at the FBI Academy in Quantico, Va. and is on the curriculum at West Point. It pioneered a psychological field he dubbed "killology, the scholarly study of the destructive act."

At the time Grossman, who has gone on to become one of the most famous, influential and controversial police trainers in the country, struck me as imminently sensible and articulate. These days, when I read some of the things he's quoted as saying I sometimes wonder if we're living in the same country; My America is not nearly so dangerous and fraught as the one he describes. But then, he's working with police, and cops understandably run to cynicism.

"Video games are great things," he told me. "They allow us to learn all kinds of skill by mimicking and rehearsing, mimicking and rehearsing. Now we've got these games that are so real, you're holding a weapon in your hand and human forms pop up on the screen and you've got a split-second to shoot them down. Bang. The gun rocks in your hand, your adrenaline is pumping, and the figure on the screen goes down, jerking, twitching, bleeding.

"And, on top of that, you're scored on a point system. It is the exact model of operant conditioning."

It also works another way.

THE LUDOVICO TECHNIQUE

Grossman likened the operant conditioning of first-person shooter games to the scene near the end of "A Clockwork Orange" where doctors attempt to instill an aversion to violence in Alex via the fictional "Ludovico Technique." Alex is subjected to nausea-, paralysis- and fear-inducing drugs while his eyes are clamped open, receiving images of graphic violence and sex. It's a classic Pavlovian kind of conditioning, the idea is he'll forever associate violence with the bad feelings he's experiencing.

We've all undergone a version of the Ludovico Technique, subjecting ourselves to thousands of hours of scenes of violence. And sure, we know they were all staged for our amusement.

But some would argue our subconscious does not know the difference, and absorbs the simulations the same way it would absorb the actual acts. Some accord dreams and visualizations the same heft as experience.

Most of us have the capacity to withstand this barrage and can, as most human beings always have, privilege real life over our fantasies.

But that's only my belief. And it's not unshakeable.

Email: [email protected]