A group of Arkansas researchers armed with a $1 million federal grant is investigating whether the lettuce in your fridge could be harboring a drug-resistant superbug.

While food safety regulations require inspectors to monitor antibiotic-resistant bacteria in retail meat and food production animals, there is no such mandated oversight for vegetables, said En Huang, lead researcher of the study and an assistant professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock.

The lack of oversight could potentially lead to people eating produce laced with dangerous germs. Considering vegetables are often eaten raw, there is a chance that drug-resistant bacteria on the produce could cause hard-to-treat infections in consumers, according to Huang.

The team of scientists from UAMS and research institutions in California and Wisconsin hope to help fill the gap with a three-year study that began earlier this month. By uncovering how antibiotic-resistant bacteria land on vegetables and analyzing enough genetic data to fill more than 83 million pages of text, the researchers aim to improve public health guidance and potentially save lives.

Huang was quick to note that as of yet there is no need to sound the alarm when it comes to infections from drug-resistant bacteria in vegetables.

Researchers looking at a piece of produce under a microscope could find up to a million bacteria cells per gram, most of which pose no risk to consumers.

"From time to time, you may hear about foodborne outbreaks linked to fresh vegetables, but this does not prevent us from eating or enjoying fresh produce," he said during a Tuesday interview.

But recent research indicates that antibiotic-resistant bacteria -- also known as superbugs -- are generally on the rise. A global study published in The Lancet, a medical journal, earlier this year found that drug-resistant germs killed more people than either HIV/AIDS or malaria in 2019.

In the U.S., more than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur each year resulting in more than 35,000 deaths, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"These are not simple numbers. These are the loss of life," said Huang. "This is my mission: to try and mitigate the risk of antibiotic resistance."

The U.S. Department of Agriculture awarded Huang and his colleagues $1 million to conduct their research after the team carried out a pilot study. The grant was among more than $5 million the agency funneled into researching antibiotic-resistant bacteria earlier this year. As the UAMS-led team conducts their study, scientists at institutions around the U.S. will be investigating drug-resistant bacteria in other parts of the food chain -- from citrus production in Florida to broiler chickens in Connecticut.

At The Ohio State University, scientists will study how potentially harmful bacterial strains may be contaminating dairy beef. Compared to other sectors of the cattle industry, meat produced from dairy cows is often neglected by researchers investigating drug-resistant bugs, according to Greg Habing, associate professor at the university's College of Veterinary Medicine in Columbus, Ohio.

When looking at the meat industry as a whole, the problem becomes increasingly challenging as the strains of bacteria that infect dairy beef can also appear in pork and poultry.

"There's a lot of different sources for those antibiotic-resistant bacteria. ... It's not really quantified what fraction dairy beef is contributing to it," Habing said during an interview Friday. "But, that said, based on some of our work so far the strains and the resistance profiles that are coming out of dairy beef are particularly concerning and we want to make sure that those are addressed."

At Virginia State University, Assistant Professor Eunice Ndegwa is leading USDA-funded research into contamination related to raising sheep, goats and alpaca, an area of the livestock industry she says has received less attention than cattle and poultry production.

Bringing researchers with different backgrounds to bear on the problem of drug-resistant bugs is critical given the various pathways open to bacteria in the food chain and the environment, said Ndegwa.

Identifying all possible routes of contamination becomes even more important when considering that bacteria can exchange drug-resistant genes.

"It should involve all of us, those who are working with food animals, with pets, with growing vegetables," said Ndegwa. "It's actually a topic that involves all professionals that work within the ecosystem that we all share."

During the first year of the UAMS study, Huang and his team plan to collect 1,200 vegetable samples, 400 each from Arkansas, Wisconsin and California. The researchers chose to focus on produce from these three states to represent the crops from the American South, West and North. The study will include samples of five popular vegetables: carrots, lettuce, spinach, sprouts and ready-to-eat salad.

In Arkansas, scientists will target vegetables sold at grocery stores and farmer's markets in the central region of the state. For vegetables collected outside of the state, Huang said researchers in California and Wisconsin would ship the bacterial DNA they isolate from samples to UAMS.

Another component of the study will involve collecting samples from two farms operating during two different growing seasons in California. At one farm, researchers will gather samples at various stages in the production process -- from the raw vegetables, the irrigation water and the packing house -- to determine at what stage, if any, drug-resistant bacteria are spreading onto produce.

At the second farm, scientists will grow their own carrots and lettuce in a controlled environment.

"We choose carrots and lettuce because they have different edible products. We eat the root of the carrots, we eat the leaves of the lettuce," said Huang. "The roots come in contact with the soil that might be one source of contamination, and the lettuce, when they do irrigation, that comes on top."

While growing their vegetables, researchers will try different methods of irrigation and different types of soil additives to see if these factors influence the presence of antibiotic-resistant germs.

After collecting the vegetable samples, the researchers will separate any bacteria harbored by the produce. Scientists will then subject the microorganisms to antibiotics to see if any survive.

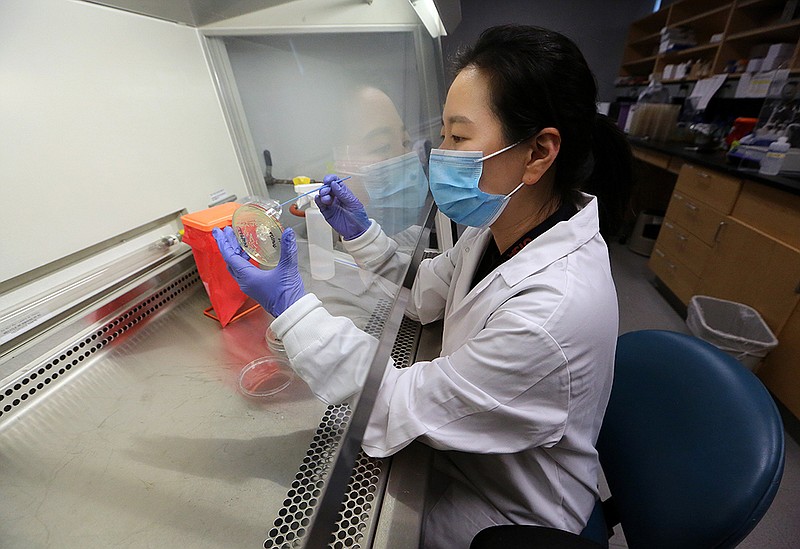

"That antibiotic can help to select our resistant bacteria," said Sun Hee Moon, a postdoctoral researcher at UAMS.

With samples of drug-resistant bacteria in hand, Huang's team will begin analyzing the DNA of the germs. While the amount of genetic information the researchers will study will depend on how many bacteria survive the antibiotics, Se-Ran Jun, assistant professor at UAMS, expects the team to handle more than a terabyte worth of data.

To put the figure in perspective, a terabyte is equal to 83.3 million pages of Microsoft Word document text, according to an article published by the University of Alaska Anchorage.

To wrangle data, the UAMS researchers will rely on the university's high-performance computing cluster. Jun will help build a database from publicly available genetic information against which the team will compare the DNA isolated from the bacteria they collect.

As they sift through the data, Huang's team will be carefully looking for signs of 18 drug-resistant germs the CDC classified in a 2019 report as urgent, serious or concerning threats with the potential to spread or become a challenge in the U.S.

Among the clinically relevant antibiotic-resistant bacteria the researchers are searching for are ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Huang said there are many reports of these germs, which the CDC lists as serious threats, appearing on fresh vegetables.

This family of bacteria is capable of breaking down commonly used antibiotics, such as penicillins, and often infect otherwise healthy people. In 2017, this type of bacteria caused an estimated 9,100 deaths and roughly $1.2 billion in health care costs, according to the CDC.

One most nefarious class of drug-resistant germs the researchers are searching for are carbapenem-resistant bacteria. These bugs can withstand treatment from carbapenem antibiotics, one of the latest types of antimicrobial medication.

"Normally doctors do not prescribe carbapenem antibiotics," said Huang. "I think that's the last resort."

While Huang said it is rare to find carbapenem-resistant bacteria on produce, scientists have documented its presence in field reports.

To disseminate their findings, Huang said his team would hold workshops and create a fact sheet and an online video. During the study, researchers in California will conduct a national survey to gather consumer perceptions of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in fresh produce.