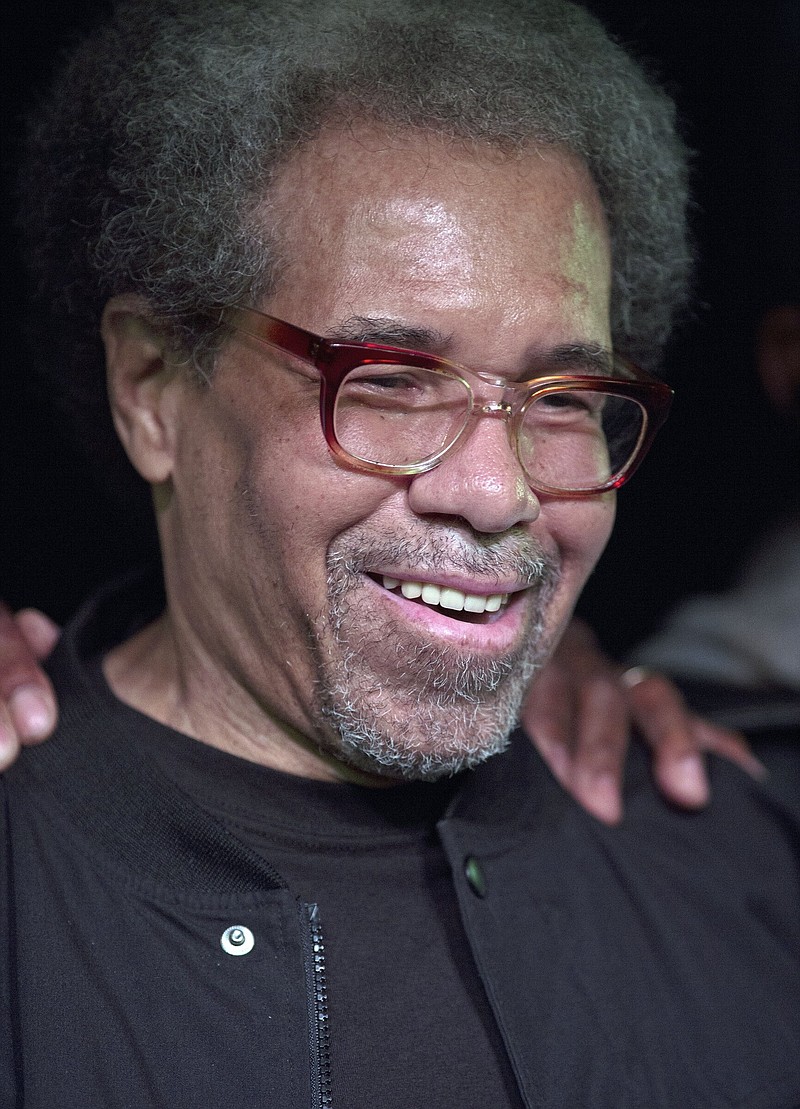

Albert Woodfox, a former member of the Black Panther organization, known for spending almost half a century in solitary confinement in a Louisiana jail before championing prison reform, died Thursday. He was 75.

Born in 1947 in New Orleans, Woodfox died there from complications of the coronavirus, his family said.

"With heavy hearts we write to share that our partner, brother, father, grandfather, and friend, Albert Woodfox, passed away" his family said. "Whatever you called him -- Fox, Shaka, Cinque or any of his other endearing nicknames -- please know that your care and compassion sustained Albert through his remarkable 75 years, and we are eternally grateful for that."

The oldest of six siblings grew from a "leader ... into liberator," they added, inspiring the United States to "think more deeply about mass incarceration, prison abuse, and racial injustice."

Woodfox had been part of the "Angola Three" -- a group of inmates, including Robert King and Herman Wallace, known for their long stretches in solitary confinement at the notorious maximum-security Louisiana State Penitentiary -- a former plantation using enslaved people that was turned into a prison known as Angola.

The men said they believed they were targeted for institutional cruelty because of their political beliefs after they set up a prison chapter of the Black Panther Party at Angola in 1971.

Woodfox spent 43 years and 10 months in solitary confinement and is thought to have served more time in solitary than any other prisoner in U.S. history, according to his attorneys.

He said in 2020 that it had been "a horrible experience." He said his mother and his association with the Black Panther group gave him "internal strength to endure" and a "purpose" and "self-worth" to get through the unending isolation.

In jail, along with King, Wallace and others, he would study history and law, teach other inmates how to read and write and play games made up in cells. They also organized strikes and protests over prison conditions, racial injustice, sexual abuse, work hours and clothing, he said. "We dared to resist," he said. He added, "We were very influential."

"They put me in a cell ... for the sole purpose of breaking my spirit," he said. "Our cells were meant to be death chambers. We turned them into high schools, universities, debate halls, law schools."

Woodfox was sent to jail in 1965 on an armed robbery sentence and put into solitary in 1972, accused of killing prison guard Brent Miller. Woodfox consistently maintained his innocence in Miller's death, and Amnesty International and other human-rights organization have long decried the case against him as evidentially flawed.

He was freed in 2016 on his 69th birthday. King was released in 2001, and Wallace was released in 2013 and died days later of cancer.

Woodfox later published a memoir titled "Solitary" written with his partner Leslie George in 2019, documenting his time confined in a 6-by-9-foot cell for 23 hours a day. It became a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award.

"I still had moments of bitterness and anger. But by then I had the wisdom to know that bitterness and anger are destructive," he wrote. "I was dedicated to building things, not tearing them down."

In the short part of his life spent outside jail, he became an avid public speaker and champion for prison reform and racial justice, saying he did not want his mind to remain imprisoned.

"I think what I went through has made me a better man, a better human being," he said. "I've been asked a lot: 'What would I change in my life?' And people are surprised when I say, 'Absolutely nothing.'"