By September 1921, school boards across Arkansas knew exactly what immorality looked like, and they were ready to nip it — nip it in the bud.

Boy-distracting herds of raccoon-eyed, red-mouthed flapper girls in diaphanous hosiery were slouching toward Hollywood to be reborn as actresses. But not from this community. Not from our public schools.

In Clay County at tiny Knobel, a former timber town near Corning with about 400 residents and an American Legion post, the school board issued a clear and numbered code of conduct for pupils. (Other school districts did this, too, and still do.)

On Day One at Knobel High School, Principal N.E. Hicks read the rules aloud, including No. 3: "The wearing of transparent hosiery, low-necked dresses or any style of clothing tending toward immodesty in dress, or the use of face paint or cosmetics, is prohibited."

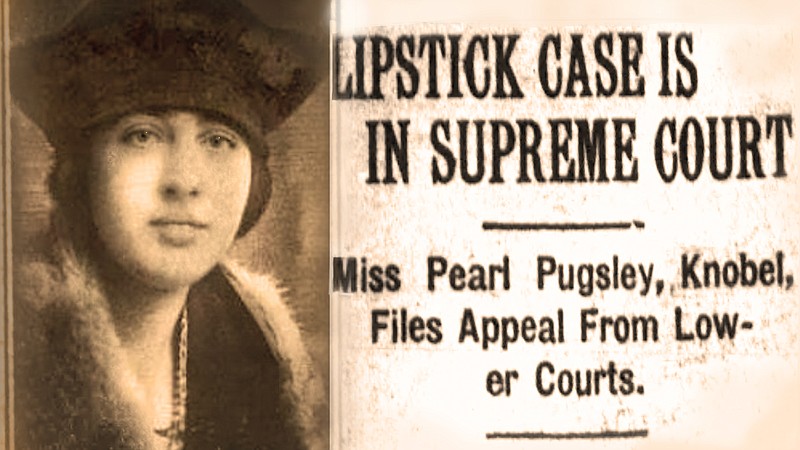

Teachers sent three girls home to wash their faces. Among them was 18-year-old Pearl Pauline Pugsley. Daughter of James B. Pugsley, merchant, she wasn't wearing cosmetics, she said, only a little talcum powder to prevent chapping. But home she went.

When she returned to school without washing her face, Hicks refused to let her in.

So, her father talked to his lawyer, and Pearl Pugsley filed suit against the school board — F.J. Sellmeyer, J.R. McCoy and B.A. Scott.

James Pugsley doesn't appear in the vast majority of the vast number of (gleeful) stories and editorials written over the ensuing year and a half about what was quickly dubbed "the lipstick war" even though lipstick was not involved. But in the archives of the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat, he can be seen in 1911-12, suing someone who required a translator over a promissory note; and again in 1916, foreclosing on a mortgage with the blessing of the state supreme court; and in the high court again in 1917, winning an appeal over Mrs. Lou Tyler in a case of alleged reckless driving in which Pugsley's car startled Tyler's wagon team and the wagon overturned, causing injuries. (See arkansasonline.com/1115book.)

So, her father was familiar with defending his rights in court.

The St. Louis Post Dispatch quoted Pearl as saying that her father told her and her mother to fight "to the finish." And so the lawsuit Pugsley v. Sellmeyer survived some discouraging delays. A big one was the resignation in September of Circuit Judge F.V. Neely. Replacements stood in for him, but the docket became overloaded.

W.W. Bandy was filling in when Gov. Thomas McRae set the date for a special election to replace Neely. Bandy was also a candidate for the judgeship. The Pugsley case was drawing national attention, and the community was reported to be evenly divided on the merits of Pearl's complaint. However Bandy ruled could affect the election, and so the trial was postponed to April 1922.

Here's the Democrat of April 2, 1922:

"Miss Pugsley said today that she was ready for the trial. 'I am always ready to stand up for my rights because I'm Irish," she insisted. "It is not only for my rights that I am fighting, it is for the rights of those hundreds who have written to me to continue my fight.'"

The day before issuing his ruling, Bandy denounced the anti-cosmetics rule from the bench saying that a little talcum powder wouldn't hurt boys or girls and "I think it unreasonable to prohibit children from using cosmetics." The Gazette reported that Bandy would likely give Pearl Pugsley the victory. But he didn't.

While calling the rule "arbitrary, unnecessary, unreasonable and void," he ruled that the board had not expelled Pearl, her principal acted on his own. She should have applied to the directors for relief before suing them.

The Sept. 7, 1922, Democrat reported that Pugsley v. Sellmeyer, the appeal, was headed to the Arkansas Supreme Court.

Laughing about this "lipstick comedy," the newspaper called the trial transcript "probably one of the most humorous documents ever filed with the clerk of the supreme court." In example, it quoted the cross-examination of Principal Hicks by one of Pugsley's two attorneys:

Questioned as to whether he knew a barber in a certain neighborhood, who sometimes shaved him, "the professor" declared that he did.

"He puts powder on your face, too, doesn't he," the attorney asked.

"I never request it," the principal declared.

"But he put it on there, didn't he?"

"I wouldn't swear that he did."

"You wouldn't swear that he didn't, either, would you?"

"No, sir."

It was also brought out that the principal appeared on the streets after being shaved and "powdered," and that he did not think it objectionable — not even to appear in church, Sunday School or prayer meeting, thus "powdered."

Then why object to its use in the schools, the attorney wanted to know. The principal said that he had no right to object to it elsewhere.

Somewhere in the hilarity, why this young woman doggedly pursued her case was boiled down to ethnic stubbornness:

"I merely felt that my toes were being trampled on, so to speak, and the Irish blood in me began to boil."

Left out of most every contemporary news account is a detail that suggests a deeper motive.

A few days after she sued the school board, her 49-year-old father closed his store for the day, went home and suffered a paralyzing stroke. The Oct. 10, 1921, Gazette carried a brief from Knobel reporting that J.B. Pugsley was unconscious with a fever of 108 degrees and not expected to live.

He told her to fight, and then he died.

PUGSLEY V. SELLMEYER

While awaiting her ruling from the state high court, Pearl Pugsley enrolled at Jonesboro Agricultural School. The May 14, 1922, Gazette reported:

"She says that she is determined to get an education, and that she will persist in wearing a moderate amount of powder on her face, as she deems it not only conducive to health, but that she feels it her 'duty.' She says that she notices that those persons who do not use face powders also do not use toothbrushes and combs, and that she thinks the use of all are not only conducive to good health, but also to a higher state of civilization."

On April 9, 1923, in a 2-1 ruling that has become part of case law regarding student rights in this nation, the Arkansas Supreme Court upheld Bandy's verdict. For the majority, Justice Frank Grigsby Smith wrote that Bandy was right to deny Pearl's petition even though he based his decision on faulty reasoning. The board had expelled Pugsley, and whether its rule was silly was not for courts to say because the board was acting within its authority. (Read that opinion here: arkansasonline.com/1115VS.)

Reporting the outcome, The New York Times noted that the Knobel district no longer had a class of high school students and so had set aside the rules, as they were not necessary.

Pearl Pugsley moved on, and not to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In May 1923, she married Armit Greer, and they moved to Indiana. Pearl lived to be 89 and, according to her obituary in the Sept. 23, 1992, Indianapolis Star, was survived by four children, 21 grandchildren, 34 great-grandchildren and five great-great-grandchildren. She is buried near Armit at Floral Park Cemetery at Indianapolis.

Email: