JOHANNESBURG -- F.W. de Klerk, who shared the Nobel Peace Prize with Nelson Mandela and as South Africa's last apartheid president oversaw the end of the country's white minority rule, has died. He was 85.

Frederik Willem de Klerk died of cancer at his home in the Fresnaye area of Cape Town, a spokesman for his foundation confirmed Thursday.

De Klerk was a controversial figure in South Africa where many blamed him for violence against Black South Africans and anti-apartheid activists during his time in power, while some white South Africans saw his efforts to end apartheid as a betrayal.

"De Klerk's legacy is a big one. It is also an uneven one, something South Africans are called to reckon with in this moment," the Mandela Foundation said of his death.

Retired Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu, another towering anti-apartheid activist, issued a similarly guarded statement about de Klerk's death.

De Klerk "played an important role in South Africa's history ... he recognized the moment for change and demonstrated the will to act on it," said Tutu's foundation.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to watch » arkansasonline.com/1112apartheid/]

However, de Klerk tried to avoid responsibility for the abuses of apartheid, including in his testimony at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was chaired by Tutu. At that time, Tutu expressed disappointment that de Klerk did not fully apologize for the evils of apartheid, the statement noted.

Even posthumously, de Klerk sought to address this criticism in a video message in which he said he was sorry for his role in apartheid. His foundation released the video after announcing his death.

"Let me today, in the last message repeat: I, without qualification, apologize for the pain and the hurt, and the indignity, and the damage, to Black, brown and Indians in South Africa," said a visibly gaunt and frail de Klerk.

He said his view of apartheid had changed since the early 1980s.

"It was as if I had a conversion. And in my heart of hearts, I realized that apartheid was wrong. I realized that we have arrived at a place which was morally unjustifiable."

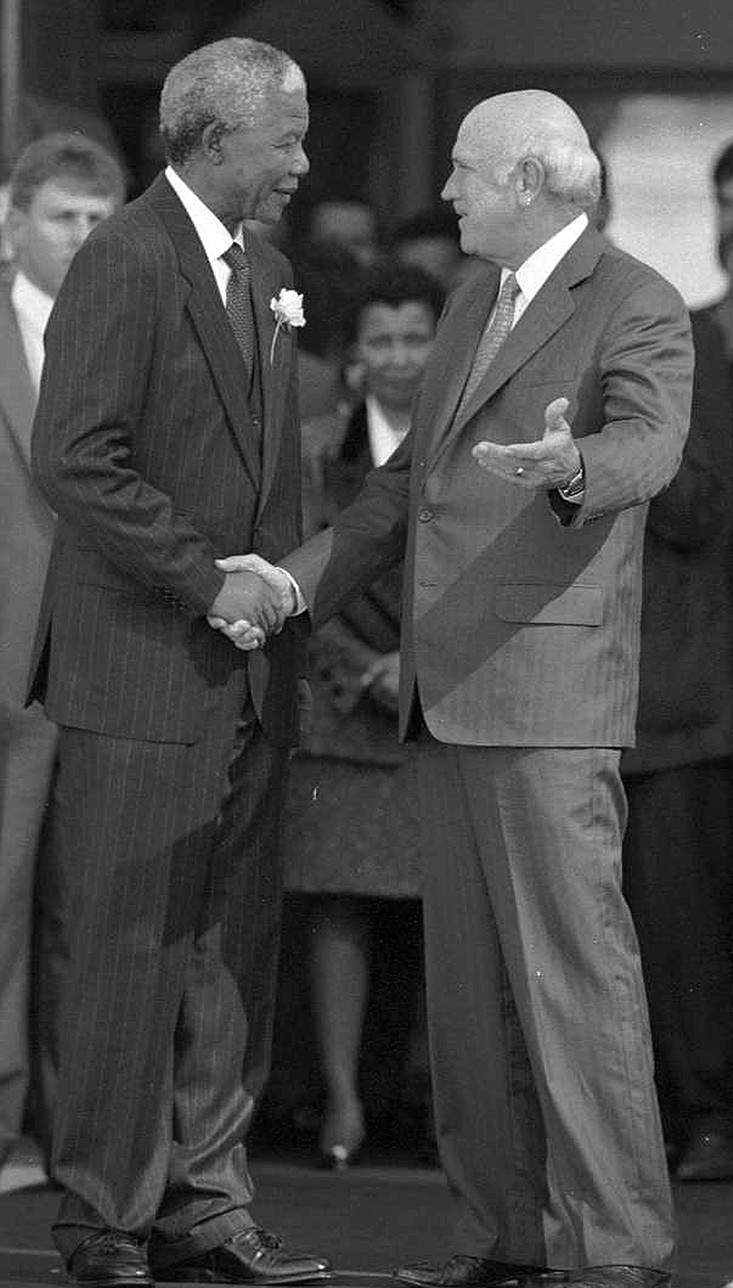

It was de Klerk who in a speech to South Africa's parliament on Feb. 2, 1990, announced that Mandela would be released from prison after 27 years. The announcement electrified a country that for decades had been scorned and sanctioned by much of the world for its brutal system of racial discrimination known as apartheid.

With South Africa's isolation deepening and its once-solid economy deteriorating, de Klerk, who had been elected president just five months earlier, also announced in the same speech the lifting of a ban on the African National Congress and other anti-apartheid political groups.

Nine days later, Mandela walked free.

Four years after that, Mandela was elected the country's first Black president as Black South Africans voted for the first time.

By then, de Klerk and Mandela had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993 for their often-tense cooperation in moving South Africa away from institutionalized racism and toward democracy.

The country would be, de Klerk told the media after his fateful speech, "a new South Africa." But Mandela's release was just the beginning of intense political negotiations on the way forward.

The toll of the transition was high. As de Klerk said in his Nobel lecture in December 1993, more than 3,000 died in political violence in South Africa that year alone. As he reminded his Nobel audience, he and fellow laureate Mandela remained political opponents, with strong disagreements. But they would move forward "because there is no other road to peace and prosperity for the people of our country."

After Mandela became president, de Klerk served as deputy president until 1996, when his party withdrew from the Cabinet.

De Klerk and Mandela argued bitterly. Mandela accused de Klerk of allowing the killings of Black South Africans during the political transition. De Klerk said Mandela could be extremely stubborn and unreasonable.

Later in life, de Klerk said there was no longer any animosity between him and Mandela, and that they were friends, having visited each other's homes.

Despite his role in South Africa's transformation, de Klerk would continue to defend what his National Party decades ago had declared as the goal of apartheid: the separate development of white and Black South Africans. In practice, however, apartheid forced millions of the country's Black majority into nominally independent "homelands" where poverty was widespread, while the white minority held most of South Africa's land.

De Klerk late in life would acknowledge that "separate but equal failed."

F.W. de Klerk was born in Johannesburg in 1936. He earned a law degree and practiced law before turning to politics and being elected to parliament. In 1978, he was appointed to the first of a series of ministerial posts, including Internal Affairs

In February 1989, de Klerk was elected the National Party leader, and in his first speech called for "a South Africa free of domination or oppression in whatever form." He was elected president in September of that year.

After leaving office, de Klerk ran a foundation that promoted his presidential heritage, and he spoke out in concern about white Afrikaaner culture and language. He also criticized South Africa's current ruling party, the African National Congress.

De Klerk is survived by his wife, Elita, and two children.