It was the small-town childhood of the 1950s that exists now only in memory and perhaps existed then only when viewed through rose-colored glasses. In Zeek Taylor’s boyhood hometown of Marmaduke, Ark. — population 650 — no one locked their doors. Kids rode their bikes all day and played outside until dark, catching lightning bugs and shouting “Red rover, red rover, send Cheryl right over.” Before bedtime, they washed their feet, dirty from being bare all day, and said their prayers.

“It was idyllic, and perhaps best described as growing up in Mayberry,” Taylor muses. “My mother’s mother lived a few blocks from my family and came to our home daily when I was a child to help care for me and my sister while my mother worked in her beauty shop. Even though my grandmother, Eva Belle Harvey, only had an eighth-grade education, she was a great storyteller. I hope and think maybe I inherited some storytelling ability from her. Although not book smart, she was one of the smartest, hardest-working and kindest persons I’ve ever known.

“My grandmother and my very supportive parents did help me become the person that I am,” he adds. “They supported me in every endeavor, even when pursuing the arts, an area they didn’t understand. They always told me that, ‘You can do it.’ I believed them and still think all things are possible.”

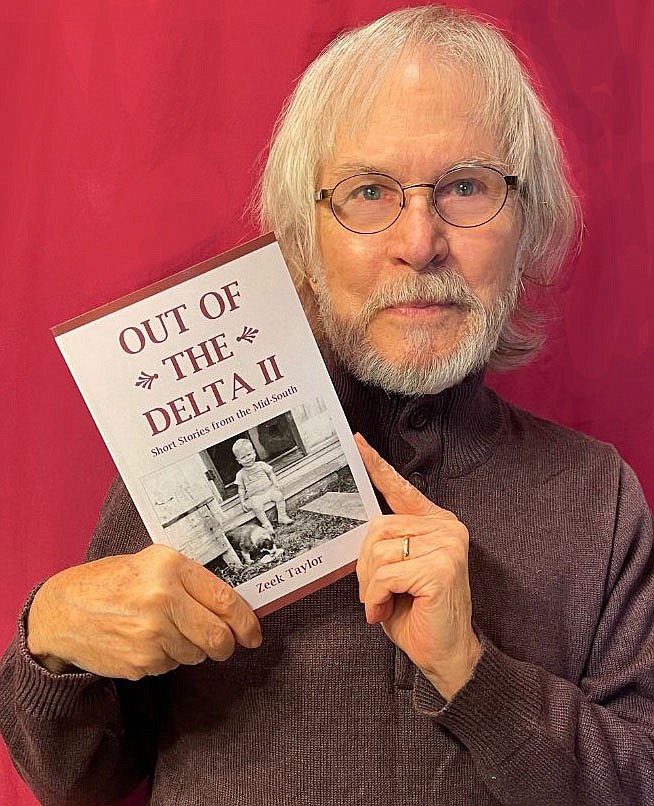

A well-known Eureka Springs artist and highly visible member of the LGBTQ community there, Taylor is now 74. While visual art has always been his forte, he also calls himself an “accidental author,” prompted by an appearance on National Public Radio’s “Tales From the South” and encouraged by telling “Throwback Thursday” stories on Facebook. Just released, “Out of the Delta II” is the second of his autobiographical collections.

“Like the stories in my first book, the stories in ‘Out of the Delta II’ are stand-alone short stories of true-life experiences,” Taylor explains. “They chronicle all phases of my life. Even though written in random order, I have attempted to put them into chronological order in my book. The true-to-life characters in my books are family members, new and old friends, pets, and people who have influenced me. The book follows me from my childhood in the Arkansas Delta to living in Missouri, Memphis, Fayetteville and finally Eureka Springs.”

Taylor says he was always an avid reader, starting with Little Golden Books and eventually including the four daily newspapers his father had delivered to their home.

“While my paintings, especially the florals, do bring me back to memories of my grandmother, who taught me about gardening and shared her love of flowers with me, I particularly liked reading human interest columns, and I think my style of writing was influenced by those columns,” he muses. In “Playtime,” he shares his summer hideaways.

“My parents owned three big lots in town,” Taylor writes. “Our house sat on one of the lots. The lot next to the house had fruit trees growing on it along with my father’s very large vegetable garden.

“The third lot was overgrown with Johnson grass. My father would let it grow tall so that I could play in the head-high grass. He taught me to use a sling blade to carve a pathway into the center of the grass-covered lot, where I would clear out a huge circular room in the middle. I would leave the cut grass on the ground. When dried, it made a thick dried pad that kept additional grass from sprouting. My friends and I spent many summer hours in the grass room. Sometimes my male friends and I pretended it was a fort on the Western frontier. Other times, while playing with my younger sister, Rhonda, and her dolls, it would become a cozy home.

“I didn’t have a treehouse, but I did have a tree ‘nest,’” he adds. “There was a tree next to one of the outbuildings in our back yard that was partially covered with honeysuckle vines. I climbed high up into the tree and formed the vines into a large bird’s nest. It was large enough and strong enough to accommodate four kids. It was the perfect hide-away and a good place to smoke dried grapevines and not get caught.”

That might be the first glimpse of the young Taylor as a rebel. He adds that the one place he was not allowed to go as a child was the sawmill. Of course, that’s where he went.

“We were warned to stay off the huge mounds of sawdust because they could collapse, bury us, and we could suffocate,” he remembers. “We didn’t listen. After the sawmill workers went home for the day, we would climb to the top of the mounds and surf down on our butts. Before heading home I carefully shook the sawdust out of my hair, pants and shirt.”

But only once did he manage to worry his parents.

“On that day, a friend and I decided to play at his father’s cotton gin. We were 10 years old. It was summertime and since it was not ginning time, there were very few workers on site. We climbed a ladder to the top of a very large metal silo-shaped storage bin … and climbed down the interior ladder to the bottom. There was enough sunlight coming in through the entrance hole that allowed us to see.

“Once inside we couldn’t talk loudly for fear of being heard, but we could talk loud enough to enjoy the echo-like reverberation of our voices. We ran in circles inside the huge cylinder until we were exhausted. When a train roared by on the nearby Cotton Belt railroad track, we would scream and then we would laugh.

“Two or three hours after entering the bin, we heard people calling our names. Our parents had become worried when we were more than an hour late returning home for supper. Half the town had been out looking for us. We yelled back, and we carefully climbed to the top. I poked my head out the opening at the top of the bin. I was quite surprised to see both sets of parents and 20 or more townsfolk standing down below. They applauded. I looked at my friend, and I could see the relief on his face. We were not in trouble. Our folks were just glad to find us alive and unharmed. We received hugs and were made to promise to never go into the bin again. We promised.

“I kept my promise, and I did not go back into the bin at the cotton gin.

“I did go back to the sawmill.”

Taylor says he’s been lucky not only in life but in art and storytelling: “I rarely suffer from artist block or author block. Sometimes story ideas just pop into mind, and especially seem to come to me while lying in bed in the morning or when I’m in the shower. I try to remember the ideas long enough to add to a list of possibilities. I also get many ideas for stories from looking at old photos.

“Because I am primarily a visual artist, I like to include visuals in my books by using photos. If the old adage, ‘Every picture tells a story’ is true, I think if my words do not, then maybe the photo will.”

In “Out of the Delta II,” Taylor is seen as a boy of 4 or 5, dressed up in a suit and bow tie for a portrait with his first rescue dog, Jiggs; with his sister, Rhonda, his “partner in crime”; with his mother, grandmother and other important women in his life; and with his Beatles haircut in Memphis, Tenn., where he attended art school and met the great love of his life. But it’s the stories that really paint pictures of his journey.

Along the way, he never lost touch with his roots in Marmaduke.

“As an adult when I returned ‘home,’ I always entered the back door, and I often found my mother sitting in her usual spot, my supper on the stove, and the television blaring. She spent more than 60 years in that house and if not working in her beauty shop, she spent the better part of her time in the kitchen. Hundreds of meals were prepared in that crowded space.

“When I received the call one morning that my mother had suddenly passed away, I immediately drove the six hours to that old house in the little Arkansas Delta town. It was a sad day when I entered that unlocked kitchen door and my mother’s chair was empty. The kitchen in my boyhood home was very small. The memories created there are very large.”

So are all of those in “Out of the Delta II.”

“Hidden Gems,” a new 2021 column about books and authors, will appear Sundays in the Profiles section. Email Features Editor Becca Martin-Brown at [email protected].

Read More

‘Out of the Delta II’

Signed copies may be purchased at $22 including shipping through zeektaylor.com, and unsigned copies are available online through Amazon, Barnes & Noble Booksellers, and Books-A-Million. At this time, there will not be book signings because of covid-19 concerns.