The ongoing covid pandemic erased most of the gains the state had made in getting children out of foster care, according to records and state officials.

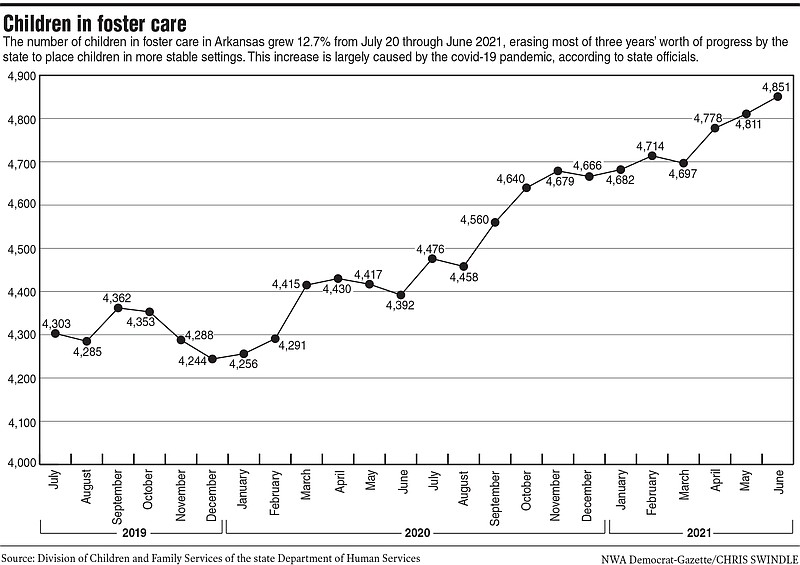

As many as 5,200 children were in foster care before 2016, records show. The number of children in foster care in Arkansas went from 4,303 in July 2019 to 4,851 by the end of June 2021, a 12.7% increase in two years.

"I had five texts and nine telephone calls in the last 24 hours, each one for a different child needing foster care," said Dennis Berry, a foster parent from Hot Springs.

The pandemic also has delayed the time it takes the agency to close an investigation.

The state Division of Children and Family Services does 29,000 investigations of child abuse or neglect a year. The number of those that weren't concluded within the division's guideline of 45 days had averaged fewer than 100 for the last several years. The figure was more than 600 at the end of June, division records show.

"Let me be clear that we see children within 24 to 72 hours so that overdue investigation is just that -- cases that are not closed out within 45 days," division administrator Mischa Martin said.

Whether a child must be seen within 24 or 72 hours depends on the type of maltreatment alleged. If a law enforcement agency requests assistance, the call is answered right away, she said.

"Children are being seen," Martin said.

The average case worker for the division has gone into quarantine more than once since the pandemic began, she said. They either caught covid or were exposed to it, state records show. Those quarantined workers do as much of their jobs as they can from home and in isolation, but their absences strain an agency already shorthanded.

More than 20% of case workers for Children and Family Services contracted covid at some point, state records show. This happened despite the personal protection equipment the agency provided, Martin said.

Precautions to slow the spread of covid also slow efforts to place children who are in the state's care into adoptions or other permanent placements, she said.

"Covid and kids who are positive and relatives and foster parents who are positive make placement much, much harder," she said. "When that child may be positive for covid, when the foster parent may be positive for covid, when that relative might be positive for covid -- figuring out how to quarantine and manage all that has definitely added an extreme layer of stress to everybody involved in the process."

Rep. Charlene Fite, R-Van Buren, is chairwoman of the state House committee overseeing Children and Family Services.

"Covid has thrown a monkey wrench in everything," she said Wednesday. "It's made it harder to hold training sessions for potential foster families, it's delayed court hearings and it's quarantined foster and potential foster families."

The situation Martin and Fite describe is true, said Jennifer Ferguson, deputy director of the nonprofit Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families.

"The state should use some of its American Rescue plan funding to help shore up the workforce in the Division of Children and Family Services," Ferguson said Thursday. "That could include hiring bonuses for new employees and higher pay for existing caseworkers to give them the incentive they may need to stay on the job during this difficult time. Without enough caseworkers to help determine the best permanency plan for children in the foster care system, the caseload only grows."

Hit harder than most

The pandemic hit Children and Family Services harder than many agencies within the Arkansas Department of Human Services, said department spokeswoman Amy Webb.

Webb said all divisions of the department -- including front-line staff at facilities that provide around-the-clock care for residents -- have had to deal with crisis and issues and the pandemic has made it harder.

"The mission her team does is among the most difficult in state government," Webb said, referring to Martin and her division. "Working to make sure the kids are safe and dealing with child abuse and neglect is a very difficult job.

"They have stepped up and are doing amazing work in the face of enormous challenges," Webb said.

Ferguson said she understood there are many demands for help and a share of the federal covid disaster relief money, but argued care for foster children should get greater attention than most.

"I'm sure many state agencies would want to use Rescue Plan funding to raise pay, but what could be a higher priority than the foster care workforce?" Ferguson said. "Their employees are charged with the safety and well-being of abused and vulnerable children who are in our care. Children's immediate needs should rise to the top of the priority list."

Ferguson also said she hopes agency leaders are encouraging staff to get vaccinated. The agency is, Webb said.

"We are doing everything we can to encourage vaccinations," Webb said, including bonus pay for getting vaccinated, holding vaccination clinics in Human Services Department facilities and the central office, working with local pharmacies to hold vaccinations at offices around the state and forming a covid response team to answer questions one on one about vaccinations.

Still, vaccinations are not required, Ferguson said.

"This is an example of why we need to repeal Act 1030, the law that prohibits the state from requiring vaccination documentation 'for any purpose,'" Ferguson said. "The state should have the leeway to require vaccinations of employees in certain positions, especially if it can help protect the children they serve."

All the difficulties Children and Family Services workers go through are also difficulties faced by foster parents, said both Berry and Lauri Currier, executive director of The Call, a nonprofit group supporting foster and adoptive parents. Both said the number of foster families is not growing as fast as the number of children needing care.

"It's going to take all of us working together to get through this," Currier said Friday.

It is hard to recruit new foster parents at large gatherings such as church services, for instance, when such large gatherings are curtailed by covid precautions, Berry said. Active foster parents are faced with tough choices between meeting the needs and admitting when they have done all their family can do, also, he said.

"Foster parents are people who want to help," Berry said. "Now they're having to say no, and that is a trauma."

"We're all part of the same team," Berry said of foster parents and Children and Family Services. "We all feel the same pressure."

A good trend reversed

"Arkansas was trending down and then literally the pandemic hit," Martin said. "The trend lines started going up. Everybody wants to think it's entries" of more children into the system. "It's not. It's not entries, it's exits. We're struggling to exit kids from foster care.

"Once the pandemic hit, the discharges just significantly declined."

Reuniting families, finding adoptions or finding other lasting solutions is more difficult during a pandemic for a host of reasons, she said.

Courts shut down temporarily, including family courts. Providers of key services such as counseling and parenting lessons had to curtail their support.

"When you have adoptions, kids have to actually meet families and you have to have that engagement to determine whether that's an appropriate family," she said. "That stopped for a period."

The situation was improving, Martin said, then the current wave of covid started.

"This pandemic not only affects your work, it also affects you personally," Martin said. "So, when our staff have some of the hardest jobs out there to assess safety and work with families in crisis, there's also dealing with their own personal struggles that might be due to the pandemic as well. So we have seen increased turnover and we have seen that workers are really, really struggling to balance both getting the work done as well as their personal lives."

Having a child of their own contract covid, for instance, has caused workers to leave, she said.

As the load on remaining case workers increased, the division prioritized opening an investigation and seeing children who are reported victims of abuse, Martin said. But something had to give, and the division fell behind on wrapping up investigations already in progress.

As of June 30, Pulaski County alone had 224 overdue investigations. That figure has since gone down, Martin said.

"I do believe in child welfare, things snowball," she said.

Pulaski County division workers experienced unusually high turnover last year. Increasing caseloads for those left made the turnover worse, she said. Kids from outside Pulaski County often go to foster parents there since Pulaski County has a high proportion of foster parents living there, she said.

As of July 29, the division had 12 workers with active cases of covid and 242 who had recovered from a bout of the disease. The division also had 15 workers in quarantine and 1,157 who had been in quarantined at various times.

"To put that in context, I have a little under 1,100 field staff," Martin said of the 1,157 quarantine incidences. "And that is specifically field staff," not central office workers.

Quarantined workers could work from home, Martin said. But they could not make home visits, transport kids or family members or other such work. Work with such close personal contact is vital to getting children from foster care into a permanent home.

"None of those tasks can happen when you are quarantined," she said.

As of July 21, the division had 1,097 staff, which is 183 short of the 1,280 positions the division has available, a 14.3% gap.

"All of my positions are assigned, in advertisement, in the process of hiring," Martin said. "I don't have any positions where I'm not actively trying to put a body in."

More News

Web watch

State Division of Children and Family Services: humanservices.arkan…

The Call, a nonprofit group supporting foster parents: thecallinarkansas.o…