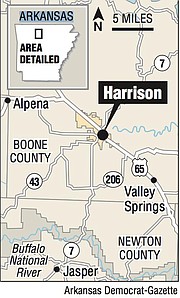

HARRISON -- The Rev. Joanne Walker Flowers has moved to Harrison to be senior pastor at First Christian Church.

Flowers, who is Black, said she read on Wikipedia that Harrison is "the most racist town in America."

"I took it with a grain of salt because you don't know who writes those articles," she said.

Flowers said she felt God directing her to Harrison.

"I realized that if this is what God wanted me to do, everything would be OK," she said. "Based on the impressions that I got from the Holy Spirit, my life would not be complete if I did not

go to Harrison. I believe this is where I'm supposed to be."

So in late August, Flowers and her husband, Virgil, moved from Weatherford, Texas, to Harrison. They found a parsonage stocked with food, including plenty of lemon bars. Rev. Flowers had mentioned she likes lemon.

[Video not showing up above? Click here to view » https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-dAyJIOA_ak]

Flowers preached her first sermon in Harrison on Sept. 6. She had a little trouble coaxing an occasional "Amen" out of the congregants. They're still getting used to one another.

Flowers said the kindness she has encountered in Harrison has exceeded her expectations.

"The people have been more than accommodating, loving," she said. "And I'm not just talking about people in the church but people in the community. I believe people have been so friendly that it's sort of a backlash because people are letting us know that this depiction of Harrison in the media is not who they are."

Harrison's image problem dates back more than a century.

"The Harrison Race Riots of 1905 and 1909 drove all but one African American from Harrison, creating by violence an all-white community similar to other such 'sundown towns' in northern and western Arkansas," according to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

Then, in the 1980s, Thomas Robb, national director of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, moved to rural Boone County and began using a Harrison post office box for the group's mailing address.

White supremacists have advertised their sentiments on billboards along Harrison highways, claiming that "diversity is a code word for white genocide."

The city has responded with "Love Your Neighbor" and "Welcome Home" billboard campaigns embracing all races.

Black people make up less than 1% of Harrison's population of about 13,000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Since the death of George Floyd on May 25 in Minneapolis, several Black Lives Matter protests have been held on the downtown Harrison square. Some protesters drove down from Missouri. Counterprotesters sometimes gathered across the street, armed with assault-style rifles.

Flowers said she doesn't plan to attend any of the protests.

"As a minister, I minister to people who are protesting because they want people to understand that Black lives matter, and I do believe that Black lives matter for obvious reasons," she said. "But you also have people that are saying blue lives matter. I believe blue lives matter.

"I believe I have to be bigger than any contemporary issue because I'm serving an eternal God."

When she was a hospital minister, Flowers said family members didn't care whether that person going into a loved one's room was a Democrat or a Republican.

"They need to know the person coming in is bringing the word of God," she said.

"This is not to discount protesters," Flowers said. "This is not to discount people who believe that their concerns are not being heard. That's not my job. My job, and the person I report to upstairs, says 'I don't care who they are. They're my children.'"

THE VIDEO

Between accepting the job and moving, Flowers saw a video online by Rob Bliss, who runs a marketing and advertising agency that specializes in "making viral video campaigns," according to its website at the time.

Bliss traveled to Arkansas, and stood for days outside a Walmart Supercenter in Harrison and along a highway in town, holding a Black Lives Matter sign.

Several people who passed by made offensive or threatening comments, which Bliss recorded with a hidden video camera.

On July 27, he posted a 2-minute video on YouTube with the title "Holding a Black Lives Matter Sign in America's Most Racist Town."

The video spread quickly, getting almost 2 million views on YouTube and being linked to articles on several websites, including The Washington Post's.

"All these insults and negative comments, hate-filled statements that were made in response to that sign," Flowers said. "I thought, goodness, I'd already said yes, this is where I'm going. So I sent the link to my senior pastor at Weatherford. He simply wrote back, 'OMG!' He couldn't believe it."

Within an hour, Flowers got a text message from Robin Seymore, chairman of the board of elders at the Harrison church, informing her about the video and inviting her to talk about it.

"When I first got the video, I never felt that I wasn't coming because I had already resigned, and this is what God wanted me to do," Flowers said. "But I started to let fear creep in a little bit because I said, 'is this going to be comfortable? Will the people be nice? Will it be OK?'

"And when I got her text, that told me right away that the people in this church, they do not mind having the hard conversation. I think that's what's most important. We've gotten to the point where we sort of skirt around each other. We can't have the hard conversation. The conversations that are truly going to be to heal. That is what really struck me. She reached out. She could have just ignored it, pretended it wasn't there, pretended there weren't awful things that were being said. But she reached out to me and said, 'we can have a conversation about this,' and I thought that was outstanding."

Seymore recalled, in her text about the video, suggesting that Flowers 'Watch it, process it, call me or any of us with any questions or if you have any sort of hesitation.'"

"I totally would understand if she changed her mind [about moving to Harrison]," Seymore said. "Nobody would have faulted her for it."

But the video didn't stop Flowers from moving to Harrison.

Seymore and her family saw the video shortly after taking part in a peaceful protest in response to the death of Floyd.

"There was weeping at our house," Seymore said. "I mean, my kids saw it. They're just 11 and 13, ... they were horrified."

Efforts in the town, such as the Community Task Force on Race Relations, and Seymore's own role in a diversity council under a past employer, felt far away in the fresh pain that the video elicited.

Harrison's residents have learned that staying silent in response to racism is "not the answer," according to Seymore, although it's been difficult to maintain progress against racism as a town.

"We do have a [race relations] problem, and I think the misconception is that we just don't try to deal with it," she said. "I feel like we had taken a couple steps forward, and [Bliss] set us at least 10 steps backwards. We have to start over all the time. We can't ever get traction because we're always trying to catch up.

"I would say we're not silent anymore, but we definitely get drowned out by various things like billboards or post office boxes."

Meanwhile, in Seattle, Flowers' daughter, Leah Blanton, said she couldn't bring herself to watch the video, although she knew her mother wouldn't step back from her decision to continue on to Harrison.

Flowers reassured her daughter. She also reassured Blanton's 20-year-old son, who had helped his grandparents move their belongings from Tennessee to Texas, and was planning to help them with the move to Harrison.

"That's the thing with my mother," Blanton said. "She doesn't usually shy away from major challenges. She's not the kind of person who can sit quietly in the background. That's not who she is.

"She's lived through a lot, done a lot, and so this is like another challenge."

THE CHANGE

Flowers was born and raised in Louisville, Ky.

She got her undergraduate degree from Central State University in Wilberforce, Ohio, then went to work in research and development for Whirlpool Corp. in Benton Harbor, Mich.

Flowers said she "got bored" and decided to join the Army. She was in one of the last classes of the Women's Army Corps. That's where she took one of her first courses in epidemiology.

She earned a master's of science in environmental health from East Tennessee State University in Johnson City, then got another master's from the University of Pittsburgh. Flowers then got a doctorate in environmental health sciences at the University of Texas School of Public Health.

Later, she was the environmental epidemiologist for the state of Washington for seven years and spent another seven years as chairman of the Department of Public Health at East Tennessee State.

While teaching in Tennessee, Flowers said she felt like "something changed."

"I felt that God had started playing around in my life, and that is when I began to sense that I was being called into something bigger than myself," she said.

Flowers was also finishing out a career in the Navy.

"At the time, I had achieved the rank of commander, and I was well on the way to making captain when all this started, when I began to sense that I was not on the right path, that there was something else I was supposed to do," she said.

Flowers spoke with a Presbyterian chaplain, who knew she was from a disadvantaged section of Louisville.

"He looked at me and he said, 'I believe that you are being called. Now is the time for you to repay some of those blessings that you have been a recipient of.'"

"I'd had the opportunity to travel, to study the things and do the things that my heart desired," she said. "So there did seem to be this certain correctness or rightness about 'now it's time for you to give back to what has given so much to you.'"

"So that gave me a different way of looking at what was going on in my life," Flowers said. "It sort of was a correction in my path, in my goals."

Through prayer, meditation and reading the Scriptures, Flowers said she began to realize that God was calling her to attend seminary.

"I was thinking, 'Heck, I've got more degrees than a thermometer. The last thing I need to do is go back to school yet again,'" she said. "But nevertheless it wouldn't go away. That was what I felt that I should be doing."

Flowers said she was raised a Missionary Baptist, which doesn't allow women to be pastors.

She remained a member of a Missionary Baptist church while attending Emmanuel Christian Seminary in Tennessee. The president there introduced her to Rev. Cynthia Hale, the pastor of a Christian megachurch in Decatur, Ga., who mentored Flowers for several years.

"That helped a lot, because I wasn't getting any guidance at the [Missionary Baptist] church that I was attending," Flowers said.

The seminary was also Flowers' introduction to the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) faith, which -- with the Christian Churches/Churches of Christ; and Churches of Christ denominations -- falls under the umbrella of the Stone-Campbell movement that arose during the Second Great Awakening, according to a history of the Disciples.

The denomination's history also notes that the earliest congregations of the Stone-Campbell Movement in Kentucky and Pennsylvania included Black and European American members. Women have been ordained ministers in the faith since the late 1880s, making the Disciples of Christ denomination one in which Flowers could pursue her call to ministry.

The denomination's identity statement underscores its adherence to ecumenism and inclusion: "We are Disciples of Christ, a movement for wholeness in a fragmented world. As part of the one body of Christ we welcome all to the Lord's Table as God has welcomed us."

Flowers said her life was changed by a mission trip she took to Kenya. She was ready to move there, but her husband didn't want to leave the United States.

Flowers said she's been to Cuba, Haiti, Turkey, Portugal and China.

"I've just been so blessed to be able to travel to all these places and bring a word of encouragement, a word of hope, to the people," she said.

All of that missionary work was before she was ordained in 2013.

THE SEARCH

Out of the many profiles that First Christian's search committee read, Flowers met the criteria that was most important to the congregation in their next pastor: they sought a person who prioritized ministering to the sick and the needy, who had thorough Biblical knowledge and preached Scripture.

Flowers and the committee became acquainted during Flowers' first interview with the church. Her second interview took place after she read about Harrison's background.

"We told her, 'there's stuff out there you ought to look at,' ... and while we believe we're a very welcoming, friendly community, there is this news out there," said Jessica Milamcq FJ, chairman of the search committee at the church in Harrison.

Rev. Danny Couch, the senior pastor at Central Christian Church in Weatherford, said he wasn't surprised when his associate pastor of a year and a half told him that she'd been called to a church in Arkansas. She'd been the first Black clergy to join the staff at the church, which also has a predominantly white congregation.

"I think she's ready for this next chapter," Couch said. "I think she spent a year and a half being prepared for what she's being called to do there, whatever that might be."

"I felt that God brought me there to show me things, and to allow me to grow in areas that I didn't think I needed to grow," said Flowers, who echoed Couch's sentiment that Weatherford had been preparing her for the work she's doing now in Harrison.

Flowers reiterated that the decision to go to Harrison and lead at First Christian Church was the will of God.

"I would say God has a way of letting us know what his will is," she said. "He has a way of letting you know which way to go next. And so that's how I found myself in Weatherford, Texas, and that's how I find myself here in Harrison."

THE PARSONAGE

Volunteers worked to prepare the parsonage inside and out in the weeks after Flowers accepted the call to move to Harrison, which Milam acknowledged had been "run down" when their new pastor first arrived to visit the town.

"Our church came together, and we joked that we were like a show on HGTV, that we really just took this step and made it into this beautiful home," Milam said. "I think [Flowers] was cautious when she got here, that she would think that we had just maybe done a little superficial stuff, but people put such love and effort and time into the details ... the landscaping and light fixtures and painting and everything that we did.

"You just felt like that was a physical gift of how excited we were for her to be in our community and in our church home finally," Milam said.

Before giving the sermon on her first Sunday in front of the congregation, Flowers thanked the members for the treats they'd left throughout the parsonage -- scented soaps, fruit baskets, breads; those lemon bars supplied with her in mind. The landscaping and work on the parsonage was a "major transformation," she said.

"Virgil and I were still finding little treats in cabinets and scented soaps and all sorts of little things that tell us that we're loved," Flowers said. "You guys just outdid yourselves in terms of hospitality."

And on a recent Sunday, the church's electric marquee sign announced the arrival of its new pastor, while a two-sided canvas sign pulled tight by stakes in the ground proclaimed in white lettering against a black background, two words: "Love wins."