On Nov. 13, 1862, the Confederate government advertised in the Charleston Daily Courier for 20 or 30 "able bodied Negro men" to work in the new nitre beds at Ashley Ferry, S.C. "The highest wages will be paid monthly," the ad stated.

It was odious work. The nitre beds were large rectangles of rotted manure and straw, moistened weekly with urine, "dung water," and liquid from privies, cesspools and drains, and turned over regularly, according to accounts at the time.

The process was designed to yield saltpeter, an ingredient of gunpowder, which the Confederate army desperately needed during the Civil War.

The wages for this repulsive task went, of course, not to those toiling in the beds, but to their owners.

The National Archives has made available online a trove of almost 6,000 Confederate government payroll records that account for money issued to hundreds of owners and others for the work of the enslaved.

The records provide a glimpse into the system in which a vast workforce -- more than 29,000 people just in Virginia, according to historian Jaime Amanda Martinez -- was compelled to labor on behalf of a war waged to preserve slavery.

Men, women and children were forced to work in places like a Petersburg, Va., lead factory that made bullets for the Confederate army.

A thousand "hands," including laborers, brick layers and carpenters, rebuilt the old colonial installation, Fort Boykin, on the James River, for the Confederates.

Others, including "axemen," drivers, wagoners, water carriers and cooks helped build forts around Richmond and along the Appomattox River, at Mulberry Island, near Newport News, and at Chaffin's Bluff and Drewry's Bluff.

They wrestled anti-ship obstacles into the James River in Virginia, the Dog River in Alabama and the Yazoo River in Mississippi.

They worked in the Confederate "shoe shop" in Columbus, Ga. They molded bullets at the arsenal in Selma, Ala., and staffed military hospitals and river steamers. They split rails and made harnesses and drove ambulances.

They built the defenses around the vital Confederate salt works at Saltville, in southwestern Virginia, later the site of a massacre of black Union cavalrymen who had been wounded in nearby fighting.

The payroll documents came from Confederate records seized by Union forces after the war and now held by the Archives, said Claire Kluskens, who headed the digitization project.

The enterprise began because researchers were interested, the records are fragile and technology enabled it, she said. "It seemed a good investment of our time," she said. The project took seven years and was completed in January.

The documents are detailed government receipts signed by owners or their representatives acknowledging that they had been paid for the use of the people they enslaved. The papers, many torn and faded, required extensive, time-consuming conservation. All of the documents had been folded and unfolded numerous times.

"And a lot of these records had attachments glued to them," she said. They had to be unglued to be digitally scanned. One document had so many attachments that it was 13 feet long.

While the number of records processed was 5,971, more than 8,000 pieces of paper were actually digitized, said Archives project coordinator Halaina Demba.

In the tattered forms were the details of oppression.

In May 1862, the Confederate government paid out $1,182.75 for the work of 52 enslaved people on the fortifications around Wilmington, N.C. The payment voucher described the occupation as "ditcher."

In March 1863, it paid $2,162.79 for 114 enslaved workers at the Confederate States Central Laboratory, a munitions facility, in Macon, Ga. Ten of them were cooks.

In June 1863, owners were paid for the work of the people they enslaved in the "Manufacture of Small Arms of All Kinds" at the armory in Macon, according to the receipt.

The practice of owners hiring out the enslaved was already long established, and many slaves were sought as skilled craftsmen. Almost always, the owner pocketed the money earned but sometimes allowed the worker to keep a small portion. Some saved enough to purchase their freedom this way.

And historians knew that, amid the other crimes of slavery, the Confederate government hired or forced thousands of enslaved people to labor for the war effort, while owners reaped the income.

(Thousands more enslaved people took the opportunity for freedom and escaped to areas controlled by the Union army. An August 1864 voucher states that of 102 enslaved people at a Macon munitions facility, 65 managed to flee.)

The Archives payroll project provides names of often anonymous slaves -- first names only -- the places where they labored, the work they did and for how long. It designates who was paid and how much. And it names the slave owners or their representatives.

One notable slaveholder, "R.B. Rhett," was probably the notorious Robert Barnwell Rhett, the proslavery Charleston "fire eater" and former U.S. senator who led the crusade for South Carolina to leave the Union in 1860, sparking the Civil War.

An 1863 voucher records a $96 payment to him for the work of eight enslaved people on James Island, near Fort Sumter, where the war began.

Many of the records come from the Confederate nitre and mining bureau, which was set up to produce saltpeter, among other things. The South was so desperate for saltpeter for gunpowder that one Alabama official reportedly placed a newspaper ad asking that the contents of chamber pots be saved for collection.

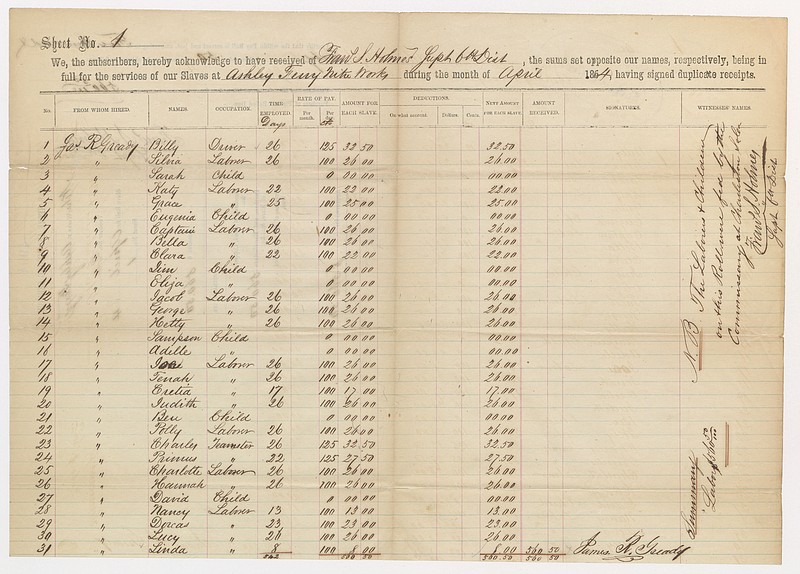

In South Carolina, in April 1864, the Confederate government hired 31 enslaved people to work at the Ashley Ferry Nitre Works, outside Charleston.

Fifteen of the "laborers" were women, and eight on the list were children. No money was paid for the children.

The government paid $560.50, roughly $17,000 today, to James R. Gready, who may have been the slaveholder or his representative.

Saltpeter could also be gleaned from certain caves. In the winter of 1863, scores of enslaved people were set to work extracting it from a huge cave in Barstow County, Ga., where they labored by torchlight in grim conditions, hauling out and processing the "peter dirt," historians say.

In many cases the enslaved had been seized, or impressed, by the Rebel authorities.

Sometimes the laborers died while working, or escaped, or were found and freed by Union forces. The so-called owners then filed claims with the government for loss of property.

After an enslaved man named Abram, who had been working for the Confederate government, disappeared when Union forces attacked Jackson, Miss., in 1863, his owner filed a claim for $4,000.

When an enslaved man named Charlie died after working in Mobile, Ala., a claimant, E.E. Kirwen, begged officials to "do what is right for a poor man who has two sons in the service and only one negro man left."

His claim was filed in December 1864. The war ended four months later, and his claim was marked "suspended."