ALBANY, N.Y. -- Advocates say the 2017 death of a prisoner illustrates how New York's prison system fails to ensure the safety of inmates who might hurt themselves if left alone in a cell.

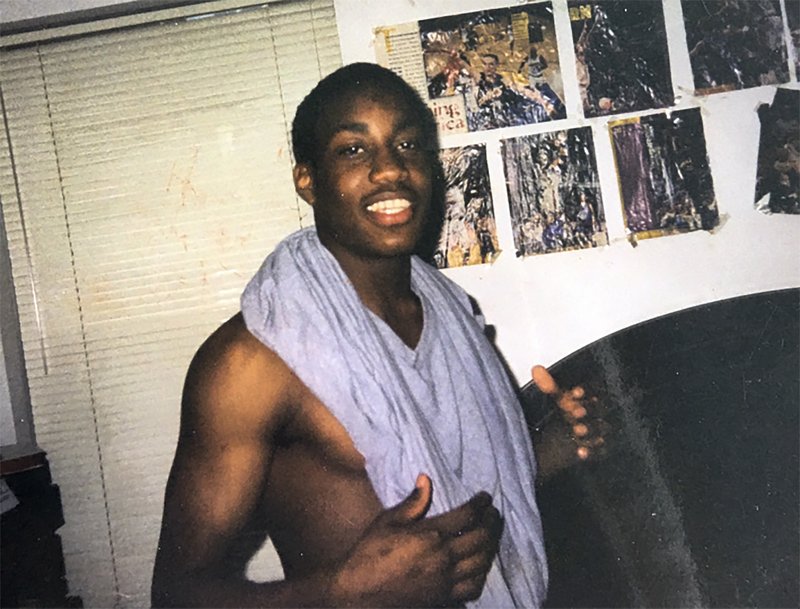

Cachin Anderson had been placed in solitary confinement, a setting experts say is often unsuitable for people who are mentally ill or trying to hurt themselves. And there, Anderson killed himself on June 28, 2017, a death a state oversight board later said could have been prevented.

New York state prison inmates in solitary confinement or long-term "keeplock" units, in which inmates are isolated, were over five times more likely to kill themselves than prisoners in general confinement, according to a report from the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision.

The report said that of the 130 inmate suicides from 2004 to 2013 in New York prisons, 30 were by prisoners in solitary or isolated housing, or a special treatment program.

New York has tried to curtail the use of solitary confinement. Earlier this year, Gov. Andrew Cuomo and legislative leaders announced a plan to restrict the isolation practice further by capping solitary confinement time to 30 days.

The state prison system has set out procedures designed to prevent suicides, too.

Correction officers watching over solitary confinement are required to make rounds every 30 minutes on an irregular basis.

Prisoners are also supposed to undergo a suicide prevention screening and a mental health assessment when they enter solitary confinement. During the screening process, prisoners found to be at an imminent suicide risk are put in the Residential Crisis Treatment Program, a separate unit inside the prison where correction officers make their rounds every 15 minutes, and each inmate is monitored under video, according to the Office of Mental Health.

Inmates in the program also have a private daily session with a mental health clinician. The program is used to find out which inmates need to be moved to the Central New York Psychiatric Center in Marcy, N.Y., for inpatient care.

But the rules aren't always followed.

In its review of Anderson's death, the Commission of Correction concluded that the 33-year-old, who was serving a 10-year sentence for involvement in an assault on a parking attendant, should have been put under a "one to one constant watch" until he could be seen by mental health staff.

"Had appropriate safety measures been taken, given Anderson's recent suicidal threats and behavioral changes, his suicide may have been preventable," the commission wrote in its report, obtained by The Associated Press through the Correctional Association of New York.

Anderson's uncle, Larry Evans, a retired corrections officer in Connecticut, said his nephew should have been under closer supervision.

"If they knew that something was going on with him, he's supposed to [be] in the unit where he's supposed to be watched -- period," Evans said.

Higher suicide rates for prisoners in solitary confinement are a pattern seen across the country, according to prison experts.

Suicide screenings, access to mental health units and restrictions on who can be put in isolation have placed New York ahead of some other states in addressing solitary confinement suicides, said Martin Horn, a lecturer at John Jay College of Criminal Justice who previously led Pennsylvania's prison system and New York City's jails.

"New York has a very robust effort to identify people with mental illness and deal with their misbehavior," he said.

But he noted New York has not gone so far as Colorado, which prevents inmates from being held in solitary confinement for more than 15 days.

In New York, some of the prison system's procedures for handling mentally ill inmates were set out in the state's Special Housing Unit Exclusion law.

The Justice Center, a state watchdog agency, has repeatedly found that prisons it inspects aren't abiding by the rules.

Eight of the 25 prisons it visited last year failed to meet existing solitary confinement regulations because mental health and suicide assessments, along with follow-up visits, were not completed in certain time frames.

The year before, the agency found that nine of the 24 facilities it visited were not in compliance.

The state prison agency, the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, did not make someone available to answer questions for this article.

The agency, in a statement, argued that the Justice Center found "minor instances" in which procedures were not followed, saying the situations are often clerical mistakes and changes were made to remedy the issue.

The department said it takes the physical and mental health of prisoners seriously and is preparing to implement the 30-day cap on solitary confinement announced this year.

A Section on 12/16/2019