"There's no Michelangelo coming from Pittsburgh," Lou Reed sings in "Small Town," the lead track of Songs for Drella, a 1990 album he made with John Cale about Andy Warhol, who had mentored the Velvet Underground, the proto-punk art rock experiment Reed and Cale had been a part of in the late 1960s.

"Drella" is a nickname Warhol's coterie used for him behind his back; a conflation of Dracula and Cinderella. He hated it.

"Small Town" is a narrative told from the perspective of the young Warhol, who had died after routine surgery in 1987. He'd grown up in Pittsburgh, the son of working-class eastern European immigrants. His father, who died when Warhol was 13, was a coal miner, though in "Small Town" Reed and Cale took a little license:

"My father worked in construction," Reed as Warhol sings. "It's not something for which I'm suited."

What Warhol was suited for, the song tells us, is "getting out of here."

The anxieties explored in "Small Town" and elsewhere on Songs for Drella will be familiar to most Americans who grew up outside one of the country's cultural capitals, and probably to many people who grew up in Los Angeles or New York City. While we might all understand that art and artists may be found anywhere human beings can survive, there's almost always a presumption of mediocrity that attaches to those who remain uncredentialed by elite institutions. There's always a voice to ask why if you're so good you're still here in this Podunk place.

Arkansas is probably close to the top of a lot of people's lists of the most Podunk places -- a lot of Arkansans might even feel this way. But everywhere probably has its own version of the Southern Inferiority Complex; every competent person (anyone who doesn't enjoy the illusion of superiority that ignorance recompenses) is bound to have grave doubts about how he or she might stack up against the best.

And so State of the Art, the Craig and Brent Renaud film about the making of a 2014 exhibit at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art that premieres today (at 8 p.m.) not only on Arkansas Educational Television Network but on the national network of PBS stations, is useful on a couple of counts.

It documents the Bentonville-based museum's groundbreaking "State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now" show, which sent co-curators Don Bacigalupi and Chad Alligood on a yearlong 100,000-plus mile road trip across the United States looking for underappreciated artists operating outside of the system. They were looking especially for artists whose work conveyed a specific sense of place and cultural identity while inviting conversations with an audience. All told, they visited the working spaces of nearly 1,000 artists, eventually choosing 227 works for the exhibit.

Most of these works would otherwise probably never have appeared in a major American museum; and the Renaud brothers' documentary serves as a kind of multiplier; more people will know about the exhibit, and especially about the seven artists featured in the film, than they would otherwise.

It's also interesting to consider that an Arkansas-based institution undertook the initiative for the show, and another Arkansas institution has teamed with the Renaud brothers -- Little Rock natives, Peabody Award winners and longtime advocates of Arkansas film culture -- to take the story of the exhibit to a national audience. It's enough to make you proud of our Podunk state.

While all this might be undone if the film turned out to be less than excellent, State of the Art is a fine if modestly scaled examination of what it means to be a working artist in 21st-century America. The seven featured artists all have interesting stories and engaging personalities, even if they produce work that subverts expectations.

Like all Renaud projects, the film is verite-style, with no narration and the camera posing as a mere observer. (Its presence turns everyone who perceives it into a performer.) Unlike almost every other Renaud project, there's no sense that the subjects are in any kind of physical danger; even a visit to an Art House maintained by performance artist/mixed-media sculptor/photographer Vanessa German in the rough Pittsburgh neighborhood of Homewood feels uplifting as she consoles a child who has recently witnessed a murder.

German, the winner of Crystal Bridges' 2018 Don Tyson Prize for excellence in visuals arts, is an incandescent personality, singing and spontaneously composing poetry on camera, who seems deeply engaged with her community, which presents as a bombed-out slum. She's a flower blooming in a vacant lot strewn with broken gin bottles and syringes.

Contrast her with methodical, thoughtful and quiet Peter Glenn Oakley, a self-taught artist (he has never taken a class) who sculpts finely detailed and precise marble replicas of everyday objects such as stacks of fast-food Styrofoam trays and disappearing technologies including typewriters and cassette tapes.

Oakley maintains a rural studio near the small town of Boone, N.C., near Asheville. He uses files and chisels from a local hardware store because there aren't any art supply shops around; and drives an ancient Mercedes diesel station wagon with "an unknown number of miles on it." ("The odometer quit working about 10 years ago at 204,000," Oakley tells the camera.) He admires it because it was one of the last cars made "by hand," without robots or CNC machines.

While he might sound like an outsider artist -- one of those grace-touched Howard Finster types -- Oakley seems possessed of a deep intellect. His work interrogates American industrial history while referring, at least in his materials, to classical Greek and Roman sculpture. This is richly conceptual art that looks perfectly representational.

One thing the Renauds don't do is spend too much time with Bacigalupi and Alligood (both have since departed Crystal Bridges), though an earlier scene suggests there might be another kind of movie -- a kind of buddy-comedy road flick -- buried with the more than 600 hours of footage that was shot for the project. (Some of which might eventually find its way onto screens somewhere; even if it's only in the Crystal Bridges archives.)

That's an entirely defensible choice given the constraints of television programming, but there's so much that's fascinating in the brief glimpses we get of the featured artists, it's natural to wonder about the ones who didn't make the cut.

At a preview screening for the movie in Little Rock a couple of weeks ago, artist Guy W. Bell -- whose work made the "State of the Art" exhibition but who isn't featured in the documentary -- provided insight into how strange it seemed for curators to make a cold call on a working studio. Bell says his profile was raised considerably after he received Crystal Bridges' imprimatur; inclusion in the exhibit serves as a calling card for artists who might otherwise be considered obscure.

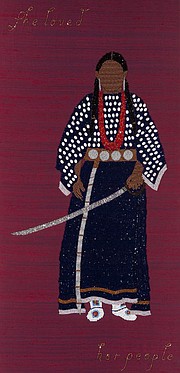

You can understand why these seven artists (the others are Fayetteville ceramicist and University of Arkansas art professor Linda Lopez; painter/sculptor/musician Carl Joe Williams of New Orleans; Las Vegas' Justin Favela, who creates outlandish oversize pinatas; video portraitist Susie J. Lee of Seattle; and Kiowa beadwork artist Teri Greeves of Santa Fe) made the cut. They are all personable, verbal and articulate about their work (that they all seem to have very good dogs is a leitmotif). They're camera-ready personalities who engage the audience. But there's more to the film than letting interesting people have their say.

While it's only an hourlong program, State of the Art showcases some of the best cinematography yet in a Renaud brothers film. The American landscape becomes a character, and there's a very stylish closing shot that wonderfully bookends an opening drone shot of Crystal Bridges' bucolic Bentonville setting.

There's nothing Podunk about any of this -- it's a work of art about artists and their work. And it's made by Arkansans, for Arkansans. And the world.

MovieStyle on 04/26/2019