In fewer than three years, Mary McQueen went from self-medicating, numbing herself with alcohol, to spending her spare time playing princess with her daughter.

McQueen, now 31, was diagnosed with bipolar disorder when she was 19 but rejected the diagnosis, opting instead to cope by drinking. She didn't hear from her 4-year-old daughter's father for years. Times got tough financially.

When her daughter Aubrey was 2, she went to live with her grandmother, but McQueen got custody of the girl back a few months ago after moving to an Arkansas Baptist Children's Home designed to support single moms.

"I am medicated now, and I've come a long way through that program," McQueen said.

About 38 percent of Arkansas children, like Aubrey, are living in single-parent households, a statistic that is linked to higher rates of poverty in the state, said Rich Huddleston, executive director for Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families.

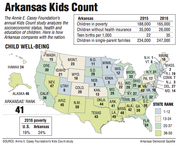

The organization works with the Annie E. Casey Foundation, a Baltimore-based group that works to improve the futures of at-risk children, to create annual rankings of the status of children in each state. Arkansas ranked 41st in this year's report, which is based on data collected in 2016.

New Hampshire ranked first, and New Mexico was last.

The rankings aren't comparable to past years because one of the measures changed this year, although the rankings are still based on 16 indicators in four categories: economic well-being, family and community, health and education.

"We are doing better in some ways," Huddleston said. "I think there's both good news and some key critical areas that show we have a lot of work to do."

About 165,000 children in Arkansas are living in poverty, and while that number has improved by 28,000 kids since 2010, the percentage is higher than the national average.

Hispanic and black children experience poverty at higher rates than white children, according to the data from Arkansas Advocates. About 40 percent of black children and 34 percent of Hispanic children in Arkansas are in poverty, compared with 17 percent of white children.

"For any kid living in poverty, it's going to have a negative impact not only on their well-being as a child ... but also the state, it definitely weakens our future workforce and economy," Huddleston said.

Nationally, the poverty rate has started to improve after years of decline following the 2008 recession, said Laura Speer, an associate director at the foundation who oversees the Kids Count project.

Single mothers in rural areas are among the most likely to live in poverty, according to a University of New Hampshire study.

"More than anything else, it's a measure of the quantity of resources that are available to a child," Speer said.

Although having a single parent does not necessarily mean a child will live in poverty, the rates of children who are poor and live with one parent are higher, Speer said. Having another person to earn a second income and to help take care of the kids makes things easier.

McQueen said things are easier financially now that she and Aubrey are living rent-free at the nonprofit, but that Aubrey doesn't yet see her as a disciplinarian because she lived with McQueen's mother for a couple of years.

About 247,000 children in Arkansas are living in single-parent households, according to the Kids County data.

Huddleston said he thinks two things may lead single-parent families into poverty: teens who have babies, and the state's high rates of incarceration.

Arkansas, where most school districts teach abstinence-focused sex education, has the highest teen birthrate in the country. The national average is 20 per 1,000, while Arkansas' is at 35.

"Anytime you have kids having kids, they are more likely to be single parents," Huddleston said.

Annette Dove, founder of Targeting Our People's Priorities with Service, said she has seen the effects of high incarceration rates on the children she works with in Pine Bluff.

Dove's nonprofit provides children with tutoring, food and a mentor program, among other services. She started work in the community in 2002 in efforts to keep the kids she previously worked with as a church youth director out of trouble. Now, her 13 programs serve about 500 children, many of whom live in poverty, she said.

"A lot of times when people are just making it, they may not consider themselves on the poverty line because they have shelter and food but they're living from payday to payday," she said.

A growing number of them have one or both parents incarcerated, she said. Some live with one parent who works more than one job, and others live with aging grandparents who are on a fixed income.

Arkansas has the highest rates of children who have experienced at least one of their parents being put in prison or jail, according to a 2017 report from the Casey foundation. The report showed that 16 percent, or 109,000, had incarcerated parents.

"There's massive impacts on the family if a parent becomes incarcerated and the resources available to that child," Speer said, adding that it is difficult to tell whether incarceration of a parent could put a child in poverty because there are too many factors involved.

Sen. Joyce Elliott, D-Little Rock, said she hopes incarceration rates can be addressed in the 2019 legislative session as part of a more comprehensive approach to tackling the state's poverty rates. She said the practice of viewing drug addiction as a crime rather than as a mental illness needs to change.

The government response to the opioid epidemic has been more focused on treatment than other addictions in the past, she added.

"That should inform us of the devastation we caused, especially in poor and black communities," she said.

Elliott was the chairman of a legislative task force established in 2009, but she said she wasn't satisfied with the results of the work.

"It [poverty] has become an acceptable reality," she said. "We hear people say things such as, 'There are always going to be poor people,' and that becomes almost an excuse not to address things in a systematic way."

One suggestion that came out of the task force was a state-level earned income-tax credit, which Arkansas Advocates has recommended implementing repeatedly, Huddleston said.

Last month, in a study on the effects of "bad policy" on black men and boys in the state, one policy recommendation was for a refundable earned income-tax credit. It's been implemented by 24 states and is designed to give money back to working people, especially those with children.

"We know that the earned income-tax credit can make a big difference," Speer said. "The earned income-tax credit at a federal level has impacted the most kids and moved the most kids out of poverty."

Elliott said the state's response can't stop there -- education, infrastructure and job creation have to be a part of a long-term solution that works.

Huddleston said his group would like to see more after-school and summer programs for children so they don't forget what they have learned. Arkansas also has higher-than-average rates of fourth-graders who aren't proficient at reading and eighth-graders who aren't proficient at math.

That's something Dove tries to provide to children in Pine Bluff. Her summer program, which has about 70 kids, focuses on reading and writing although other topics including ballroom dancing are covered.

While Elliott, a former teacher, thinks these kinds of programs are important, she said addressing poverty through the Legislature hasn't gained much traction in the past.

Often, providing help is left to nonprofits like Dove's or the Little Rock group that is helping McQueen and Aubrey.

Arkansas Baptist Children's Homes has locations for family care in Jonesboro, Little Rock and Springdale. McQueen and Aubrey stay at the Little Rock site.

About six families at a time can stay in the homes with the family care program, said Derek Brown, clinical director for the nonprofit.

"Every mom who comes to us is looking for one thing," Brown said. "She's looking to be able to take care of her kids with independence, and so she's looking for the resources to be able to have that independence."

He explained that the group has a renewed focus on reunifying families that have been separated through the state's foster-care system, which is what McQueen worked for after voluntarily giving custody of Aubrey to her mother.

After she went through rehabilitation and got medication to treat her mental illness, she got a job at a day care and a car. A judge granted her custody at the end of May. She hopes to start a career in community outreach and to eventually move into their own place.

McQueen said when she brought her home, Aubrey bounced around the house, introducing McQueen to people she already knew.

"This is my mom. This is my mom."

A Section on 06/27/2018