LITTLE ROCK -- Visitors find small diamonds at the Crater of Diamonds State Park in Murfreesboro fairly often. More than 200 have already been claimed this year, more than 30,000 have been discovered since the property became a state park in 1972, and more than 75,000 since the farmer who owned the land in 1906 found the first one.

But the chance to watch as a master diamond cutter transforms, facet by facet, a large diamond in the rough into a glistening gem? Priceless.

The public recently had the chance to do just that during a several-day event when an 8.52-carat white diamond found in the park in June was cut on the showroom floor of Stanley Jewelers Gemologist in North Little Rock. In its rough state, the diamond was the fifth largest found since the land became a state park.

Mike Botha, a master diamond cutter from Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, labored over it for up to 12 hours a day for eight days.

"It's the first one we've ever been able to watch being cut in person," says Waymon Cox, a Crater of Diamonds park interpreter. He and several other state park employees gathered at the store on the third day Botha worked.

"Diamond cutting is extremely specialized and there are only a very few people out there who do this," Cox says. "Most of the ones who've found diamonds at the park and had them cut sent them off to New York or Bismarck, N.D."

It is a rare opportunity even for those who deal with diamonds daily, says Loyd Stanley, the store's owner.

"Only about one jeweler out of every 1,000 has actually ever seen a diamond being cut," he says.

EUREKA!

It all began June 24 when Bobbie Oskarson, 33, of Longmont, Colo., on vacation with her boyfriend, Travis Dillon, visited the 37½-acre park -- the only place in the United States where the public can search for and keep any diamonds found.

After each paid the $8 admission fee, Oskarson began sifting through a mound of dirt while Dillon went to rent some digging equipment.

Before he could return, just 20 minutes later, Oskarson, an administrative assistant for a nonprofit organization, had landed her gem.

"I found it in the Pig Pen," she says of an especially muddy section of the park's search area. "You guys had just had a heavy rain and they'd just plowed up the park," she says, referring to the periodic plowing to bring more diamonds to the eroded surface of the ancient, gem-bearing volcanic crater.

"I thought it was shaped kind of funny," she says of the oblong stone. "I thought it was a quartz or a crystal."

She later took it to the park's center for a free identification.

"They took it back there and I thought they were taking a long time," she recalls. "They kept coming back out and saying 'Just a few more minutes.' I started wondering what the big deal was and worried maybe we'd done something wrong and we were in trouble. They finally came back out and told me it was an actual diamond."

The park weighed and certified the gem free of charge. She named it Esperanza after her niece. Returning to Colorado with the diamond, Oskarson found Neil Beaty of Denver, an independent diamond appraiser and a member of the American Gem Society, a nonprofit trade association. He suggested a couple of options for selling the diamond -- sell it in its rough state, possibly for $20,000, or follow the diamond through its transformation.

"I wanted the one which would get the most money," she says. "They are estimating it will sell for about six figures but we won't know until he's done."

Her plans for the money?

"I want to buy a house, pay off my bills, put away money for retirement, and maybe travel some," Oskarson says.

Choosing to have the diamond cut in Arkansas led Oskarson to Stanley Jewelers, which in 1966 became the first jeweler in Arkansas to join the gem society.

"We'd worked closely with Mr. Botha in the past; he'd come to our store for demonstrations," Stanley says.

SEPT. 8, 8.52 CARATS

The 800-pound cutting table, shipped via truck, arrives at 8 a.m., three days later than planned but just in time for Botha, president of Embee Diamond Technologies, to begin work.

His mission? Take the diamond from Murfreesboro's "Pig Pen" to a sparkling diamond ready for grading by the American Gem Society Laboratories in Las Vegas.

Botha says he has no formal education in his profession.

"It's all on-the-job training," says the 67-year-old, who began cutting diamonds in 1967.

He spent his first day getting to know Esperanza.

"When you cut the first facet, you have to make sure it's absolutely right," he says. "It's like building the foundation of the house if it's no good, the rest won't be either."

The diamond had earlier been sent to the gem society lab and tested for color and clarity. Botha, who attended that procedure, says it appears the diamond is a Type IIA, meaning it is almost, perhaps completely, devoid of impurities.

"The [gem society] has determined it has little or no nitrogen in it, which makes it harder and more difficult to cut," Botha says. "Its color is the very best and the clarity, so far as we can tell, is flawless."

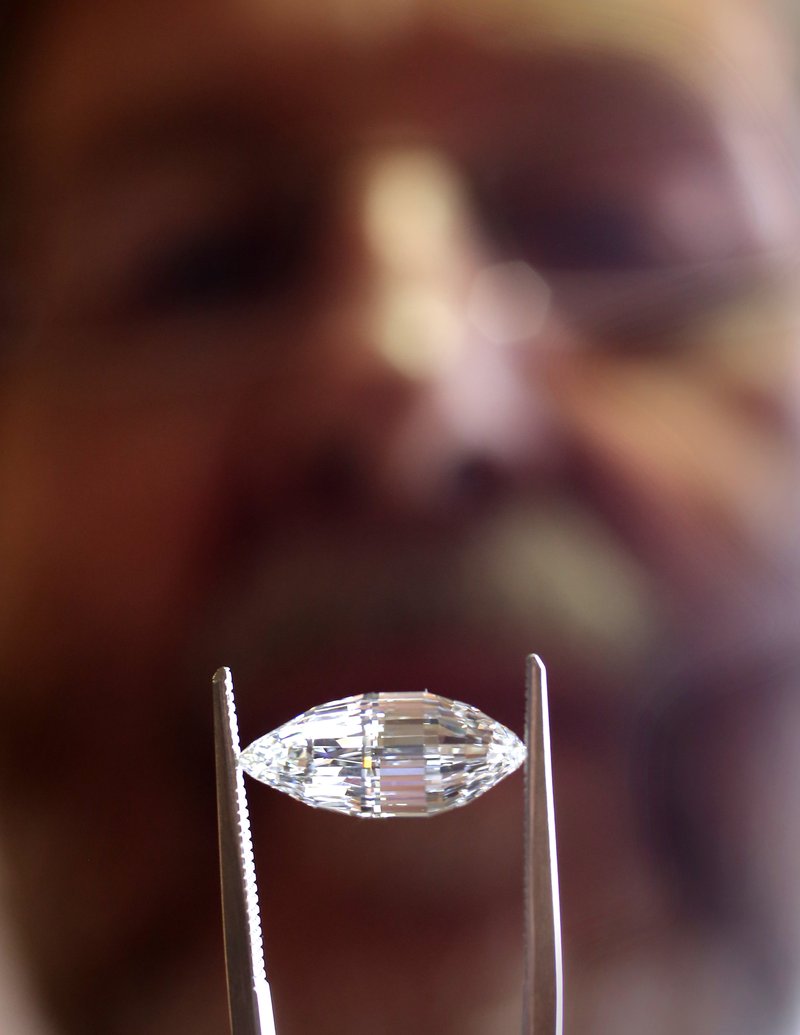

After additional 3-D testing, Botha chose to cut it in a rare triolette (three-sided) shape due to its oblong form.

The plan, displayed on a nearby laptop, calls for a complex cut of 147 facets. Botha will try to have the finished diamond retain at least 5 carats, which would bump it up to the fourth-largest cut diamond found in the state park.

In its rough state, Esperanza, about the length of a quarter, looks like an icicle.

"It is not a broken piece; this is the entire original diamond," Botha says. "This is the whole real deal."

He says the diamond will look much different two days later: "By Thursday all the facets will be there."

SEPT. 10, 6.3 CARATS

Two days later, Botha and Esperanza have become well acquainted.

"I haven't reached the tail of the elephant yet," he says, still working to establish the basic facets. In doing so, he uses diamond powder on the grinding wheel, the outer edge for more coarse grinding, the inner section for finer work.

"Maybe later today or tomorrow, I will start to polish the diamond, which will still include quite a bit of cutting."

By noon, the diamond has shrunk to 6.3 carats.

On this day, the jewelry store is filled with state employees, including Richard Davies, executive director of the Arkansas Parks and Tourism Department, Cox from the state park and those who regularly dig there, including some who've earlier found smaller diamonds.

SEPT. 11, 5.80 CARATS

On Friday, Botha's work shifts to less cutting and more polishing.

"The big chunks have been ground off," he says, often using the wrap of cloth around his wrist to wipe the diamond.

"I still have 100 facets to go," he explains. "The unusual shape and some inverted spots it has takes a lot of work. As far as color and clarity, this diamond is in a class of its own."

"She's a real gem."

SEPT. 12, 5.20 CARATS

"It's going to fall under five carats," Stanley says somberly this afternoon.

Esperanza is still no slouch. The jewel, up for sale by Heritage Auctions in Dallas in early December, is set to appear on the cover of the auction's catalog.

After Botha determines his work is done, the gem will return to the American Gem Society's lab in Las Vegas for its final grading report and possibly also go to the Gemological Institute of America in Carlsbad, Calif., for additional grading before jewelry designer Erica Courtney of Los Angeles creates a pendant for it made of platinum donated by the Platinum Guild International.

The others involved in the cutting of the diamond will receive a percentage of the proceeds from its sale, while the designer of the pendant will be paid an already established amount.

"The color just keeps on getting better," says Botha, who has finished the 63 main facets and is polishing them. "I'd say it's an A or a B."

SEPT. 14, 4.8 CARATS

"Yesterday was a hard day," says Botha, who has been averaging 10- to 11-hour workdays. "One facet took three hours to polish. Type IIA is the hardest to cut and this one is the mother of them all," he says. "It is truly painstaking work."

He says he'll be finished "when the last facet is polished," adding he originally thought he'd finish Sunday.

"I have to make sure each facet is 100 percent polished," he says of the 147 facets he needed to cut, polish and repolish. "I think I'm back on No. 63 now."

Does he ever grow weary of working on a diamond?

"When it's a real monster like a 200 or 300-carat diamond," he says, recalling the biggest one he ever worked on: a 314-carat stone that was cut into several smaller pieces that were polished afterward.

SEPT. 15, 4.67 CARATS

By 3:30 p.m., after laboring for 75 hours at his cutting table, the grinding wheel is still, Botha and Esperanza are gone, and the bulk of his work is done.

Botha took the diamond home to Canada, where he will perform some final polishing. Once Esperanza crosses the auction block she could bring as much as $300,000.

It's a dazzling return from an $8-dig in the dirt.

NW News on 09/27/2015