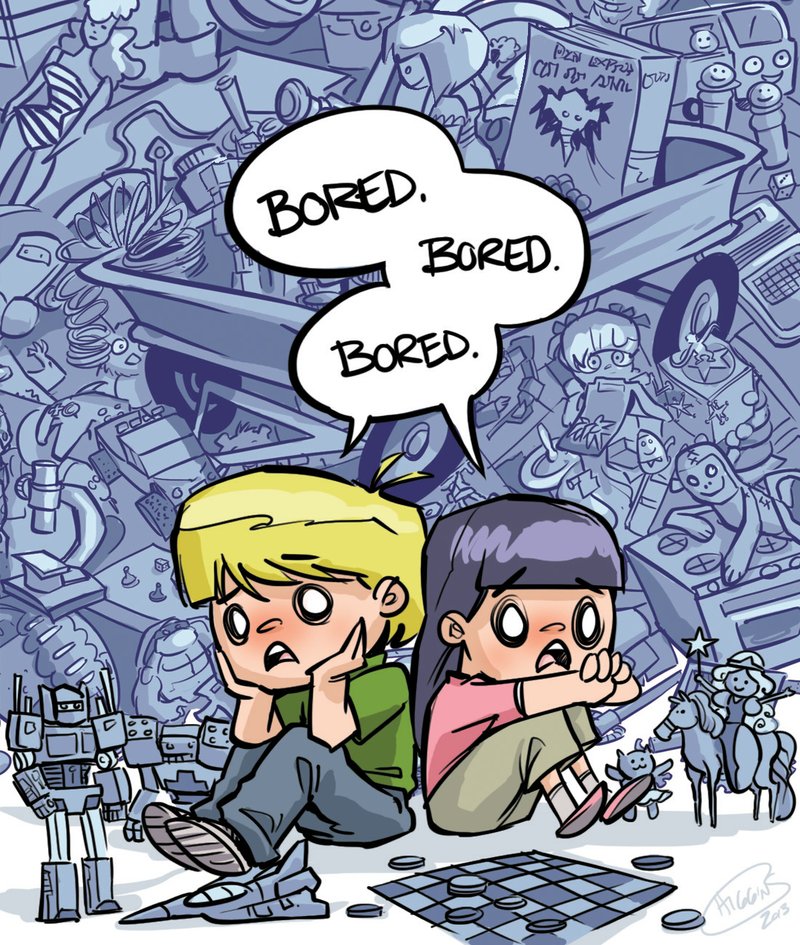

It’s fairly common to hear a kid wail during an unfortunate bout of boredom. Less common to hear is a complaint from a parent that there aren’t enough toys around to keep that kid entertained.

Even as the little ones are happily scrawling on their Christmas lists - the latest Lego play set, Xbox game or talking doll, a ball, some new blocks, an action figure - grownups everywhere are wondering where they will stow all these new playthings - and whether they should be stowed at all.

German researchers Rainer Strick and Elke Schubert wondered back in the 1980s if adult addictions might be spurred by addictive habits in childhood - habits they defined as “boredom despite or because of superabundance, the lack of perseverance, and quick frustration.” They started a project that involved removing all the toys from nursery school rooms for three months and sitting back to see what would happen.

The children in those rooms used blankets, chairs and tables to build camps, houses, even buildings with balconies and began elaborate role-playing games, their developmental need for play strong and their imaginations stoked by the lack of toys available to them at that time.

That experiment spurred some nursery schools to continue removing toys in hopes of stimulating children’s social growth and encouraged some families to follow suit at home.

Some families have not gone so far as to remove toys altogether but have taken a minimalist approach to life in general and to toys specifically.

Neither is the norm.

Researchers affiliated with the University of California at Los Angeles’ Center on Everyday Lives of Families, founded in 2001 with funding from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, wrote in the book Life at Home in the Twenty-First Century about what they saw in the homes of 32 middle-income American families.

“The United States has 3.1 percent of the world’s children, yet U.S. families annually purchase more than 40 percent of the total toys consumed globally,” according to the authors. “Spilling out of children’s bedrooms and into living rooms, dining rooms, kitchens and parents’ bedrooms, the playthings of America’s kids are ubiquitous in middle-class homes.”

PLAYTHINGS APLENTY

According to the nonprofit Toy Industry Association, Americans spent about $22 billion on toys, dolls and games in 2012 alone.

So how can parents hold onto what little bits of floor space are still visible?

Beth Scanlan of Little Rock, mother to 9-year-old Sydney and 5-year-old Jett, sorts through toys about four times a year.

“The problem is that once I’m done cleaning out their rooms I no longer have the energy to finish the process,” Scanlan says.

She has sold some toys at consignment sales, but getting things properly tagged and transported takes time and with her family, full-time job and role as PTA president time is something she doesn’t have a lot of.

She recently hauled a few loads to the home of a friend, who signed on with someone who does garage sales in exchange for 40 percent of the profits.

“The hardest things for me to get rid of are the baby things,” Scanlan admits. “For a little while, I wasn’t sure if we were done having kids. I didn’t want to just get rid of everything. Now, it’s just sentimental.”

Scanlan’s friend, Leah Dawson, also of Little Rock, knows that feeling.

“It’s really hard for me to get rid of toys that hold sentimental value,” Dawson says. “But then you kind of get overcrowded. You have to do something.”

Her mother-in-law saved almost all of the toys her husband played with growing up.

“But back then, for Christmas, they may have only gotten one or two things,” she says. “His toys were special because there were so few, not like kids today.”

MEMORY MAKERS

Dawson’s mother was more of a minimalist, leaving Dawson wistful for some of her favorite toys, like the Barbie McDonald’s play set she had when she was 10.

“That’s one of the things I really wish I had. I remember the little burgers and the little french fries. I try to think about what my children will wish they had when they’re adults, either for their own children or just to have,” she says. “But it’s hard.”

She kept, for example, the real metal cowboy spurs she and her husband searched for right up until Christmas Eve when her now-16-year-old stepson, Nick, was 4.

“I will have those forever because that’s just a fun story for us as a family. And they don’t take up a lot of room,” she says. “My problem is that I always want to keep too much.”

Her daughter, 17-monthold Allie, is still too young to help, but Dawson and her son MacKean, 9, sort toys together, deciding what to keep in his bedroom, what to put in the attic for safekeeping and what can be donated or passed on to friends.

Scotty Smittle, clinical director of Chenal Family Therapy’s Conway office and father of six children between the ages of 8 months and 9 years, says that even though some parents may find it easier to take toys out of the play area without their little ones knowing, Dawson’s approach is the right one.

“We don’t want to send the message that if you turn your back we take your toys away. I’ve seen kids and even seen adults that I’ve worked with who grow up with the idea that mom and dad got rid of my favorite toy without my knowing and they harbor this resentment about it,” Smittle says.

Those resentments can be overcome by replacing old memories with new ones, but that’s not the easiest process, of course.

Beyond that, “I think a good rule of thumb, and one we use in our home, is that if a child hasn’t played with a toy in six months you don’t need to have it in your house because it’s just taking up space,” says Smittle, who adds that much of his toy-related advice comes from his wife, Leslie.

He doesn’t think there’s a certain number of toys each child should have.

“I think that there can be too much. I know that at my house there seem to be too many toys,” he says. “I just don’t think you can put a number on it.”

ENCOURAGING ENTREPRENEURS

Unused toys at the Smittle house go into piles to be donated, passed to friends or sold, thus encouraging children to part with their playthings by blessing someone else with them or by making money to buy different playthings.

Smittle suggests giving older children the opportunity to list some toys on Internet sale sites, such as eBay.

“They can take a picture of the toy, write a good description,” he says. “There are language skills there, there are entrepreneurial skills … there are all sorts of skills you can teach there that they’ll need for life by using this process.”

Lisa Langenfeld, owner of The Organized Edge in Bentonville, says that, currency aside, involving children in decluttering is crucial to learning.

“It teaches them at a young age about how you go through that process. Kids are sponges,” she says.

Her clients are often amazed by how much space is freed up just by getting rid of things that are broken or have pieces missing. But she makes no judgment calls on how many toys are in the homes where she does her work.

“There are some parents who prefer to limit their children’s toys because they don’t want to be overwhelmed or have too much of a sense of entitlement. There are other parents who say, ‘Yeah, get another toy!’” she says.

“I think the key is that whatever number that they have is that they’re in good working order and that they’re accessible and that they’re able to be put in a place that the child can maintain instead of having the parent go around and pick up all the toys.”

With more children, of course, comes a bigger organizational challenge, says Kim Laney, owner of A Call to Order.

She recommends grouping toys by gender, age and type of play for easy access, as well as for easy storage. Putting pictures on the fronts of bins can help younger children learn to put things away when they’re done.

And, she says, it’s not a bad idea to stash some birthday or Christmas gifts so that children won’t get so overwhelmed by the sudden influx.

“Let them cycle through those,” she says. “You can let them play with them for a while and then give them away when they’re tired of them, or put it away and bring out something else.”

Neither Laney, Langenfeld nor Smittle grew up with as many toys as their kids possess.

“What I’ve found is that the more toys you have, the more likely it is that your kids are going to be bored,” says Smittle, echoing those German researchers who championed toy-free kindergarten classes.

“There are days when they want to play with certain toys and I’ll say, ‘Today we’re not going to play with toys. We’re going to build a fort out of the couch cushions or under the kitchen table,’ because I want to foster that imagination. I want them to know that they can have fun with the stuff around them. They have a great time, but they wouldn’t do that if I didn’t allow them the space to do that by giving them minimal playthings.”

That said, the toys are still waiting on the shelves to be played with another day.

Family, Pages 34 on 12/11/2013