NORTHWEST ARKANSAS — Lantern light won’t shine on the damp walls of three Arkansas State Park caves that will close this month to prevent the spread of white-nose syndrome, a fungus that kills bats.

State park officials announced Friday that Devil’s Den Cave and Devil’s Ice Box, at Devil’s Den State Park near Winslow, will temporarily close April 16. War Eagle Cave at Withrow Springs State Park near Huntsville will also close on that date.

Other caves on public land in the state have been closed to prevent spread of the fungus. The Arkansas Game & Fish Commission has closed all caves on its wildlife management areas. Most caves at Buffalo National River are closed.

White-nose syndrome was detected in 2006 and spread through caves in the Northeast causing massive die-offs of bats, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service information.

The nearest cave to Arkansas where the fungus has been confirmed is in central Tennessee.

The fungus spreads from bat to bat. The malady is thought to be spread from cave to cave by spelunkers who carry the fungus on their equipment and clothing.

White-nose syndrome causes bats to wake from hibernation prematurely. They leave caves before insects, their primary food, become abundant. The bats die of starvation.

The night-flying mammals eat large amounts of insects each night. The impact on the environment could be severe if bat numbers plummet, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife.

Joe Jacobs, an Arkansas State Parks spokesman in Little Rock, said the three caves were closed at the recommendation of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

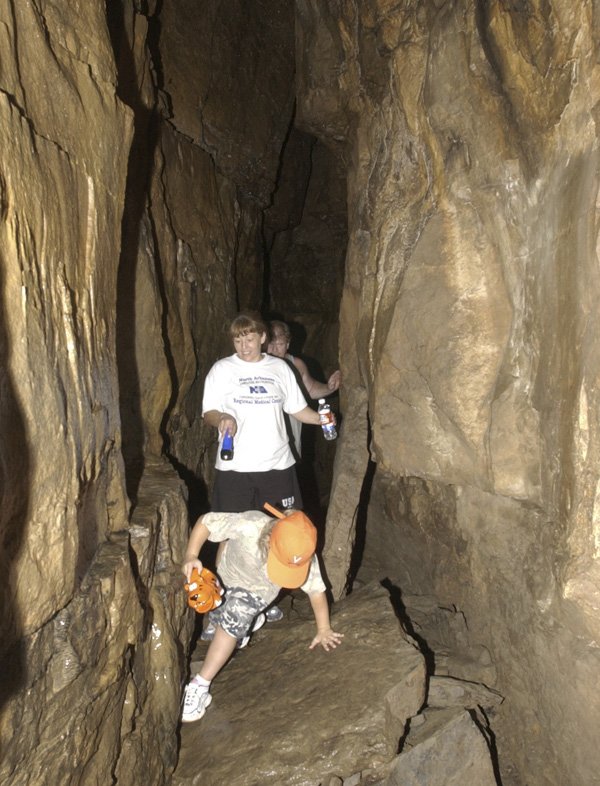

Devil’s Den Cave is one of the most visited features at the park. Superintendent Monte Fuller said 500 to 1,000 people explore the cave on a nice weekend.

He doesn’t know when Devil’s Den Cave and Devil’s Icebox will open. Farmer’s Cave, also at Devil’s Den, was closed in May.

“They’re saying it’s temporary, but we’re not putting a definition on temporary,” Fuller said. “It all depends on research into this white-nose syndrome.”

A gate will be placed across the entrance to Devil’s Den Cave. The entrance to Devil’s Ice Box is too large for a gate, so a sign will be posted.

War Eagle Cave at Withrow Springs State Park will also be posted with a sign, said Assistant Superintendent Daniel Godwin.

War Eagle Cave shouldn’t be confused with War Eagle Cavern, a commercial cave east of Rogers. That cave is open, as are all commercial caves in the region.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service doesn’t have authority to close caves on private property such as War Eagle Cavern, said Tom MacKenzie with the service in Atlanta.

War Eagle Cavern owner Dennis Boyer said Friday he’s fielded phone calls for about two years from people wondering if the cave is open.

Blanchard Springs Caverns is a commercial cave on public land in the Ozark National Forest at Mountain View. Plans are for the cave to remain open, said C.J. Norvell, spokeswoman for the U.S. Forest Service in Talihina, Okla.

“There’s no evidence we know of recreational or commercial caves like Blanchard being affected,” she said. “That’s because people who go into commercial caves aren’t people who go from cave to cave like spelunkers.”

All caves in the Ozark and Ouachita national forests are closed except Blanchard Springs, Norvell said.

Caves in Arkansas Game & Fish Commission wildlife management areas are closed.

Robert Ginsburg of Fayetteville, an avid caver, supports closing the public-land caves. He said the move will curtail some caving activity, but noted there are caves on private land that experienced spelunkers may explore if granted permission.

“The sacrifice is far less than the danger of not doing anything,” he said.

What Is It?

White-Nose Syndrome

White-nose syndrome is a condition named for a fungus adapted to cold conditions like those found in caves. It is so named because infected bats usually show a white fungus on their noses, mouths, wings or feet.

Some experts believe the fungus may be the result of a virus. At this time, only bats that hibernate in caves have been affected. Infected bats suffer a 95- to 100-percent mortality rate.

The disease is transmitted bat to bat. It is believed that cavers moving their gear from cave to cave are spreading the fungus.

White-nose syndrome has caused the most rapid decline of North American wildlife in recorded history.

Source: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service