FAYETTEVILLE -- A new law intended to allow more people to get their seized property back from the government contains too many loopholes to be effective, critics say.

And the new legislation, which takes effect later this year, does nothing to address what defense lawyers call the biggest flaw in the civil forfeiture system: Defendants are required to hire lawyers, appear in court and prove their innocence to get property back, the opposite of the burden of proof required in criminal cases.

Players on both sides agreed Arkansas' forfeiture law is unfair, sometimes causing people arrested for drug crimes but never convicted to lose their property to the state anyway. While the new law is intended to require a conviction before property is forfeited, it may not turn out that way.

It often costs more to get the property back than it's worth, lawyers said. So the owner, who is also facing a criminal charge, doesn't show up in court for civil forfeiture cases. The property is automatically forfeited in a default judgment, according to Sara Swearengin, a deputy prosecutor who handles forfeitures in Washington County.

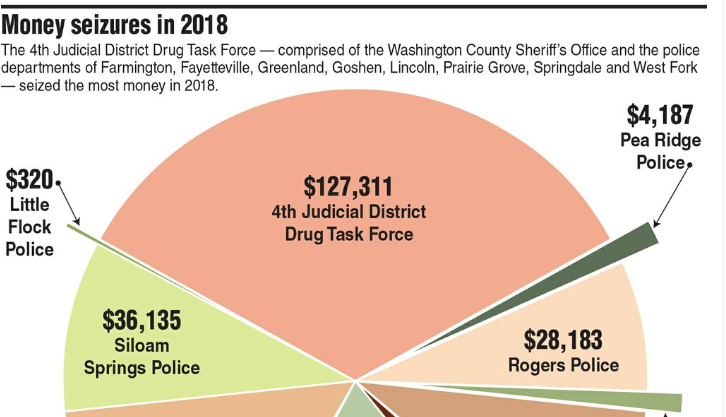

Examples from last year's seizures abound.

Bentonville police arrested a man in March 2018 on charges of possession of methamphetamine and drug paraphernalia. He was assigned a public defender in July.

The Benton County Prosecutor's Office filed a civil lawsuit later that month asking to keep the 2008 Chevrolet Aveo police seized when they arrested him. He didn't answer the lawsuit within the 60 days allowed, so the judge in October issued a default judgment, meaning his property was forfeited. The judge gave the car to Bentonville police.

The man's criminal case, meanwhile, wasn't decided until April 1, 2019, when the judge sent his case to drug court. His name isn't being used because, if he completes the program, criminal charges will be expunged. Drug Court is a diversion program aimed at keeping nonviolent, first-time drug offenders out of the criminal court system and off drugs.

A default judgment is one of seven exemptions to the new law's conviction requirement.

At least 77 percent of forfeitures ordered so far from seizures in 2018 were default judgments, according to seizure reports and court databases. The information is current as of March 19.

Prosecutors in Benton and Washington counties sued and received $90,626 from people who were charged with a drug-related crime in 2018 but have yet to be found guilty. They also kept 12 cars, two guns and some TV monitors.

For comparison, the forfeited property of those actually convicted so far of a crime from a 2018 seizure totals $56,869.

Latest law

Gov. Asa Hutchinson signed the Civil Asset Forfeiture Reform Act of 2019 on March 14. It should take effect in July. Sen. Bart Hester, R-Cave Springs, and Rep. Austin McCollum, R-Bentonville, sponsored the bill. It passed unanimously in both chambers.

The bill had the backing of the Arkansas Prosecuting Attorneys Association and criminal justice reform advocacy groups.

"This bill is a testament to finding agreement, talking through practical challenges and raising the standard to ensure our citizens have more protections in place," McCollum said after the House vote.

The new law still allows a judge to waive the conviction requirement and order the property forfeited if the owner has died, was deported, was granted immunity or reduced punishment in exchange for testifying or assisting law enforcement or a prosecution, fled the jurisdiction or failed to appear on the underlying criminal charge, failed to answer the complaint for civil asset forfeiture, abandoned or disclaimed ownership, or agreed in writing with the prosecuting attorney to forfeit the property.

Under either the old or new law, it's up to the person who has their property taken to prove it wasn't used in the commission of a crime or he or she didn't know it was being used for criminal activity.

Being acquitted or having charges dropped doesn't automatically mean the state has to return the property.

Criminal charges were never filed or were dismissed in four cases from last year's seizures, yet the prosecutor sued and was granted forfeitures totaling $13,425 according to the research. All four were default judgments.

Washington County Prosecutor Matt Durrett said a person may still be facing justice, even if a criminal case is dropped by his office.

"Sometimes a charge is dismissed or not filed because the person's a juvenile. What's listed as dismissed or not filed doesn't mean that person is not being held responsible somewhere else, in another court.

"In certain situations, a case is dropped because the U.S. attorney has indicted the individual, so our cases show it as dropped, but the money is clearly drug proceeds so we proceed with the forfeiture," Durrett said.

"We'd have to establish that there's some criminality going on," Durrett said. "There's still the requirement that there be some type of connection, either between the money or the property and illegal drug activity."

For example, Durrett's office got $1,182 last year from a man who was never charged with a crime. The man was arrested after police went to the wrong apartment, smelled marijuana and knocked on the door.

Police asked the occupant whether he had smoked pot. The young man said yes. Police asked whether he had more in the apartment. Yes, he said, including some marijuana brownies in the freezer. The man let police into the apartment where police found marijuana, a scale, a grinder, package of clear plastic bags and a black box containing the money.

Because the case stemmed from a police error, prosecutors didn't file criminal charges against the man, but they received permission from the court to keep his money.

By default

Forfeiture actions, being civil in nature, fall under the legal rules of civil procedure, according to John Threet, a circuit judge and former Washington County prosecutor.

"Since it's civil, a default is treated the same as any other civil case," Threet said. "If you don't answer after being served with notice, the prosecutor doesn't have to go through proving the case."

But, Threet noted, the evidence for the forfeiture would have been included by the prosecutor when he filed the case.

Of the 116 forfeitures from property, at least 89 have been awarded by default.

Defendants represented by private counsel in their criminal case typically have their attorney file a response, and occasionally, a defendant files a response on his or her own, Swearengin said.

"The rest just don't respond," she said.

Police file a confiscation report listing all seized property, including money, when they make an arrest. The standardized form goes to the local prosecutor for review and the Arkansas Drug Director. The director's office is a division of the Department of Human Services. Director Kirk Lane also serves as chairman of the Arkansas Alcohol and Drug Abuse Coordinating Council and is responsible for coordinating alcohol and drug abuse prevention initiatives.

The property owner has 30 to 60 days, depending on whether he's in jail, to file a response to the forfeiture action.

Most forfeitures in Washington and Benton counties are for small amounts of money, a few hundred or a few thousand dollars. Of the 87 cases where forfeitures of money were ordered, 35 were for less than $1,000; 40 were for amounts between $1,001 and $3,000; and 13 were for more than $3,000.

Tony Pirani, a criminal defense lawyer, said it can easily cost more to defend those cases than the amount of money or value of the property seized.

"How much are you going to pay? Can you get a lawyer? Public defenders don't do that," he said. "So you've got to look at trying to hire somebody to handle that case."

If the person fights the forfeiture action, a trial is held in which the defendant has to prove there was no link between his property and criminal activity. Prosecutors have to prove the connection, said Benton County Prosecutor Nathan Smith. He said prosecutors have to prove an owner of a vehicle knew or should have known the driver was using the car in the drug trade before a judge will grant a forfeiture.

Pirani said the onus for proving a case should always be on the state to justify the taking rather than on the person whose property is at risk.

He likes the conviction requirement in the new law, but since it still contains the default exception for failing to answer the civil forfeiture complaint, the situation is unchanged, Pirani said.

Opposing philosophies

Pirani, a former deputy public defender in Washington County, said the forfeiture concept has strayed over the years from the intended purpose.

"The origin of this, as I've always understood it, was to kind of try to reach essentially the cartels, the people who are moving money around," he said. "It has become a law enforcement tool that is used increasingly over the years -- and in some disturbing ways -- against very low-level folks and in some pretty abusive situations."

One man who had money seized last year tried to fight the forfeiture in court. Writing from his cell in the Washington County Detention Center, the man filed a response to the forfeiture case against him acting as his own attorney.

Not all of the $1,118 taken from him when he was arrested on drug charges was related to alleged drug sales, he argued, $750 of that was earnings from his job at a chicken processing company. He asked that the $750 be returned.

The man got his day in court, one of only two people who went to trial to regain their property. Both lost.

The defendant "failed to provide sufficient evidence to rebut the presumption that any money found in close proximity" to a controlled substance is presumed to be eligible to be forfeited, the judge ruled.

Shane Wilkinson, a Bentonville lawyer and former deputy prosecutor, also said he has seen a trend where property is taken from people who are simply in possession of drugs.

"They don't have any history of selling drugs," he said. "It's supposed to be a law targeting drug dealers."

Durrett, who supported the new law, said the purpose behind the law has always been to inhibit the ability of drug dealers from profiting from the sale of controlled substances.

"The Legislature took the concern of low-level individuals into account when it prohibited forfeitures based on misdemeanor drug offenses," Durrett said.

Pirani said having drugs and cash at the same time doesn't always mean a person is a drug dealer.

"Sometimes, people just have money. You may be someone who is struggling with substance abuse or addiction issues and you may be using controlled substances," he said. "But, you also may have just picked up your tax refund and just happen to have some cash in your pocket.

"That's just straight up theft. My opinion," he said.

War on drugs

Smith said money and cars are the two top things that his office seizes because they are items mostly closely tied to the illegal drug trade. Washington County targets cash for the most part, seizing the occasional vehicle.

Shannon Jenkins, spokeswoman for the Benton County Sheriff's Office, said some of the seized vehicles are sold at auctions and others are used for law enforcement purposes.

A 2008 white Jaguar XT seized by the Sheriff's Office in July is set to be auctioned.

Deputies got the car after the driver pulled up to a house they were searching. Deputies found 8 ounces of methamphetamine and a loaded gun. They also seized $1,002.

Durrett said proceeds from ill-gotten gains and illicit money seized by civil forfeiture are used to help law enforcement agencies fight crime in their communities.

"These funds go to help fund training. It goes to help fund things like Kevlar vests, lots of things. Drug dogs, we've helped pay for drug dogs for different agencies," he said. "And, it's required that this money go to a law enforcement purpose."

Arkansas law sends 80 percent of the money from the first $250,000 forfeited in each judicial district to local law enforcement involved in the seizure and the prosecutor's office. The remainder goes to buy equipment at the state Crime Laboratory.

Forfeited proceeds of more than $250,000 per judicial district are sent to the state drug director for use in drug interdiction, education, rehabilitation, drug courts and the state Crime Lab.

Each law enforcement agency can decide how to use its money, but it must be for law enforcement and prosecutorial purposes, Durrett said.

Smith said he favors the new law because it preserves the forfeiture provision while at the same time protecting personal liberties for some individuals.

"Asset forfeiture is an important tool that law enforcement needs to maintain in order to take some of the profit out of the drug trade," Smith said. "By generally requiring a conviction in the criminal case before property can be forfeited in the civil case, this bill promotes the dual goals of due process and ensuring that drug dealers do not reap the financial rewards of their crime."

Jenna Moll, deputy director of the advocacy group Justice Action Network, said the group supports forfeitures in cases where individuals have been convicted of crimes.

"The law will maintain forfeitures as a tool for law enforcement, but ensure innocent people do not have their property taken," Moll said.

Durrett said he expects the biggest change for his office will be the matter of timing.

"It's going to change up the timing because right now a criminal conviction takes longer than the adjudication of the civil case, when you have to factor in crime lab and other reasons that cases get moved," Durrett said.

Swearengin said forfeitures are expected to take about six to nine months longer under the new law.

How it was done

Research for this report included Northwest Arkansas Democrat-Gazette staff members obtaining a copy of each confiscation report submitted in 2018 by a Washington and Benton County law enforcement agency. State law requires a copy of the report be filed with the Arkansas drug director and with the local prosecutor within three business days.

Next, staff researched each of the more than 170 cases to determine the status of the criminal case and civil forfeiture case, if there was one filed, for each seizure. If the status couldn't be determined with online court databases, the prosecutors' offices were consulted.

A computer database was built with the gathered information that forms the basis for this story.

All case information was current as of March 19.

— Staff report

Forfeited

Arkansas law enforcement agencies seized nearly $88 million in cash from 2010-18. The data include 9,976 cases in which cash was taken and a dollar amount was listed.

Of those, 51.7 percent were for $1,000 or less, and 26.9 percent were for $500 or less. Conversely, there were 15 seizures for $1 million or more, and 32 for $500,000 or more. Law enforcement also seized roughly 4,900 vehicles, at least 3,300 weapons and 1,000 other pieces of property in that span.

Source: Jeremy Horpedahl, assistant professor of economics, University of Central Arkansas

Supreme Court decision

A recent U.S. Supreme Court decision could limit how much property can be taken by forfeiture.

The court found in February that Indiana must consider whether taking a $42,000 Land Rover from Tyson Timbs, a man convicted of selling heroin, constitutes an “excessive fine” under the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution. It was the first application of the “excessive fine” clause to civil asset forfeiture cases handled at the state level.

“Vehicle seizures are going to be a little more difficult, depending on the situation, but at least here in Washington County that won’t change a lot of what we’re doing,” predicted Matt Durrett, Washington County prosecutor.

Source: Staff report

NW News on 04/21/2019