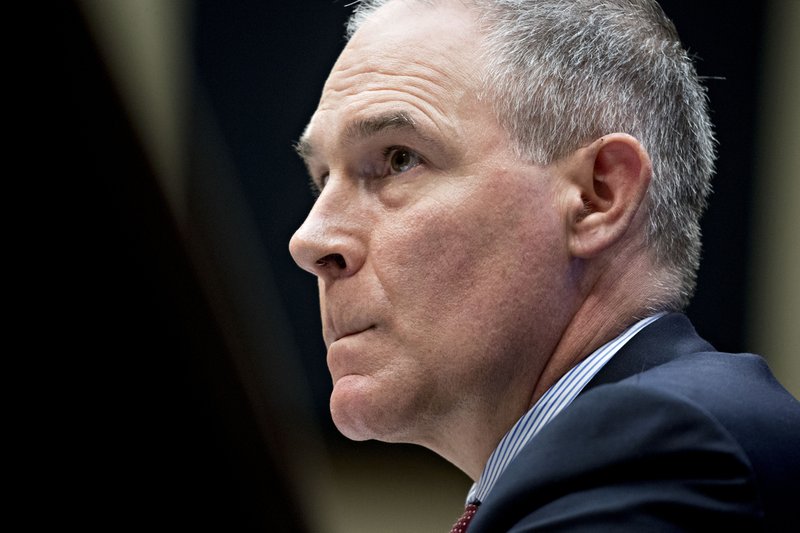

Take a moment to pity Scott Pruitt.

I know this sentiment comes as a shock. After all, in a presidential administration haunted by scandals, Scott Pruitt still stands out for the surprising pettiness of his peccadilloes.

Recently we discovered the EPA chief had turned his administrative aides and security staff--whose salary is paid by our taxes--into personal assistants in a way that would be familiar to a Hollywood producer. No task was too demeaning for them to take on. He demanded they pick up dry-cleaning and seek out his preferred skin moisturizer, one apparently only for sale at the Ritz-Carlton hotels.

True, he's hardly alone. Compare all this with the high-living behavior of some of his colleagues in the administration. Trump is the ringleader: He spent $13 million last year traveling. One weekend alone at his New Jersey golf club came in at more than $44,000. HUD Secretary Ben Carson (estimated net worth: $26 million) got caught ordering $31,000 worth of dining room furniture for his office suite, while Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and wife, Louise Linton, took advantage of a military flight to Fort Knox that was suspiciously timed for the 2017 solar eclipse. Much of this happens on the public tab, no matter how many bucks they've got banked.

Pruitt's no slouch in that department, either: He's insisted on flying first class when traveling on government business, citing security threats. But still, there is something frenzied about his spending and the way he pursues it. That probably shouldn't come as a surprise.

Economist Robert H. Frank calls the pressure to indulge in evermore high-end goods and luxury experiences an expenditure cascade. As the wealthy spend more on luxurious goods and services, the pressure increases for everyone else to do the same. That's something that's defined our second gilded age, as almost all of us can attest. We've seen this effect in our own lives in everything from coffee to baby strollers, handbags to houses.

And now we see it from Scott Pruitt, a middle-class striver in a rich man's administration, courtesy of his spot in Trump's Cabinet, the wealthiest ever assembled by a U.S. president. It was sociologist Thorstein Veblen who coined the term "conspicuous consumption" during the first gilded age. In his view, we are not simply spending for the sheer joy of it. It is instead a form of signaling status, a visual way of demonstrating power. Pruitt is the latest, or at least the most notable, figure to embrace that tendency.

We judge ourselves by the company we keep. And while you and I find ourselves keeping up with the Joneses, Pruitt finds himself keeping up with the Trumps (estimated net worth: $2.8 billion), the McMahons (estimated net worth: $1.6 billion) the DeVoses (estimated net worth: $1.5 billion), the Rosses (estimated net worth: $700 million) the Mnuchins (estimated net worth: $400 million) and the Sessionses (estimated net worth: $7.5 million).

Pruitt, by contrast, makes a tad less than $200,000 annually serving as head of the EPA. His net worth, according to mandatory filings: An estimated $400,000. Not riches, certainly, not take-this-job-and-shove-it-money but impressive enough for a 50-year-old career politician in the United States, a country where about 40 percent of adults claim they could not come up with $400 in an emergency without resorting to borrowing money or pawning belongings.

But it's not an adequate sum, not in the Trump administration, where Pruitt's net worth is pretty much chump change, nor in the Senate, where the median net worth is an estimated $3.2 million. (Members of the House get by with a more modest but still substantial $900,000.)

Could this, perhaps, at least partially explain Pruitt's orgy of ethically dodgy financial behavior? He's not the first pol to fall prey to this status spending. Just a few years back, we were treated to the spectacle of former Virginia Gov. Robert McDonnell, whose own dodgy financial trials originated, in part, in his family's attempts to keep up with the high Virginia society that they found themselves thrust into after his election.

After all, Pruitt's high-end skin care regimen is not the only example of his eyebrow-raising purchases and staff commands. His team also made sure he was supplied with delectables from gourmet food purveyor Dean & DeLuca. They apartment-hunted for the man, and helped him plan a family vacation to California to see the Rose Bowl. One even called the Trump International Hotel, asking whether any used mattresses were available for Pruitt to purchase, and what the sale price might be if so.

This comes on top of other Pruitt reveals, including renting a Capitol Hill apartment for $50 a night from the wife of a lobbyist with business pending before the EPA, charging the EPA for a dozen fountain pens costing $130 apiece, demanding that his security detail use their emergency sirens when he's late for dinner reservations at destinations such as Le Diplomate and dining so often at the low-cost but high-end White House mess that he was asked to show up a little less.

Give Pruitt some credit. He was, at least, attempting to save a buck. He's a self-important spender, part cheapskate and schnorrer. But self-sacrifice? A modest lifestyle? Please. This is the Trump administration we're talking about.

Common sense says the richer the company we keep--and the more high living goes on around us--the more we'll spend trying to keep up, and show off. Passing time with people wealthier than ourselves almost certainly shifts our reference points.

Many of us seem to instinctively know this. When a group of researchers led by Sara Solnick, then at the University of Miami, conducted an experiment where they asked subjects if they would prefer to earn $50,000 a year while others made do with $25,000 or instead an annual salary of $100,000 while living surrounded by those taking home $250,000 a year, about half say they would rather the lesser amount. The authors of the survey found that when they probed into the decision, they found it wasn't driven by envy. Instead, they noted, "[M]any seemed to see life as an ongoing competition, in which not being ahead means falling behind."

Watching other people spend money, it seems, encourages others to do so as well. When Pedro Gardete, an assistant professor at Stanford University, crunched the data from hundreds of thousands of airline passengers, he discovered that people are significantly more likely to purchase a snack or pay to watch a premium movie if the person sitting next to them does so first.

In this light, Pruitt's pettiness isn't mysterious at all. He's just trying to keep up in an administration where almost everyone else is far, far ahead of him on the economic food chain. It all makes sense, in a behavioral finance sort of way.

Editorial on 06/17/2018