Influenza is clearing its throat beside us in the mall, barking at us from the back pew in church, barring the door of Grandma's nursing home, making smart people hesitate as the elevator door slides open.

Flu can kill us and so, this time of year, we think about it. Over the past four decades, seasonal flu has ended from 3,000 to 48,000 Americans a year, depending on the strain that makes the rounds. But that is new news.

In Old News, Arkansans weren't thinking about flu 100 years ago this week. They were thinking about the other ways there were to die in respiratory distress, including pneumonia, fever and ague, measles. At the dawn of history's worst epidemic, "flu" was not a household word.

The 15-month pandemic known by the end of 1918 as "Spanish influenza" would kill 50 million to 100 million humans around the globe, including 670,000 Americans. That's more people than all the soldiers killed in combat during World Wars I and II. Not coincidentally, many of the dead in 1918 were soldiers in training at large Army camps, including Camp Pike in North Little Rock.

It appeared to strike Camp Pike like a fist in September 1918 after which, with 54,500 soldiers in residence, 13,500 cases of influenza were observed -- and 466 deaths (according to the War Department Annual Report of the Surgeon General for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1919).

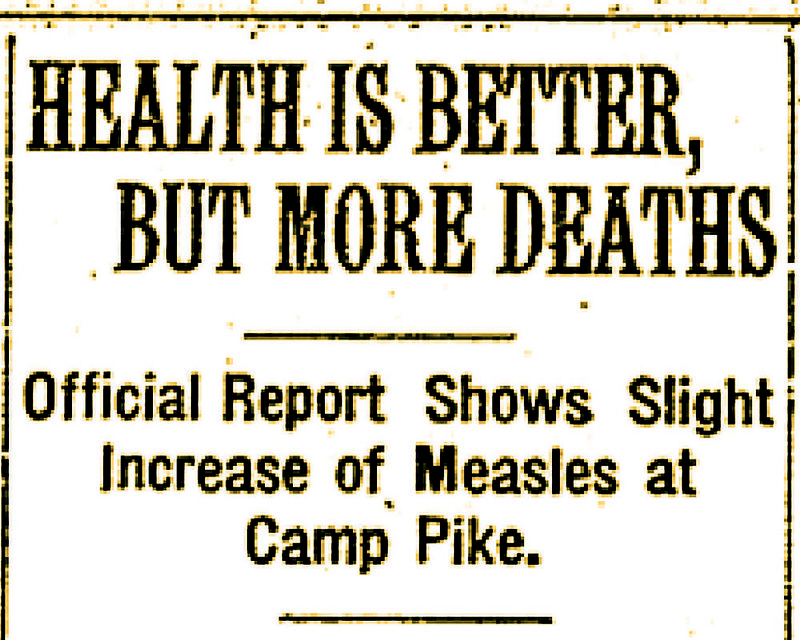

Today's research suggests the virulent strain was already spreading within the United States in January, and long before bodies piled up in an obvious way. But in fall 1918, public officials who saw the dramatic escalation of the contagion worried about panic, and they began to lie. A docile press, loathe to undermine the American war effort, quoted their reassurances that things were almost better.

I have this information thanks to Helpful Reader, who called my attention to John M. Barry's "How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America," in the November edition of Smithsonian Magazine. This alarming story is part of The Next Pandemic project posted online at smithsonianmag.com. It singles out the Arkansas Gazette as one of the newspapers that failed to document the danger at hand.

Barry writes, "For an example of the press's failure, consider Arkansas. Over a four-day period in October, the hospital at Camp Pike admitted 8,000 soldiers. Francis Blake, a member of the Army's special pneumonia unit, described the scene: 'Every corridor and there are miles of them with double rows of cots ... with influenza patients ... There is only death and destruction.' Yet seven miles away in Little Rock, a headline in the Gazette pretended yawns: 'Spanish influenza is plain la grippe -- same old fever and chills.'"

That was October 1918. Was the paper already minimizing health worries at Camp Pike earlier? Alerted by Helpful Reader, I have been scouting the archives for evidence since November 1917 and will try to keep us up-to-date with any late breaking history.

INSTANT CITY

In January 1918, readers of the Gazette and the Arkansas Democrat were well aware that between January 1917 and January 1918, 6,000 acres of dairy farm and woodland north of Fort Roots in North Little Rock had become Camp Pike, with "30,000 stalwart, up-standing, clear-eyed young men, wearing the uniform of their country," as a Gazette report put it.

Readers knew that woolen uniforms were in short supply; fuel came and went; training was rigorous labor; and the winter of 1917/18 was fierce. They also read about sickness and deaths on base.

The "Camp Pike Gazette" was a daily feature that the Gazette usually printed on Page 3, where jaunty human-interest items, Army press releases, personnel tidbits and daily news lined up side by side. The prose style varies, which suggests more than one reporter contributed; but it would make sense, based on how today's cityrooms operate, that one reporter did most of the work.

Camp Pike Gazette was local copy, but national news appeared with it, including a weekly report from Washington with adverse news about diseases in camps. For example, the Jan. 5 Gazette reported that 87 new cases of pneumonia had been reported at Camp Pike, which had a large hospital. And Jan. 11, the weekly morbidity report was headlined "Camp Pike Has Most Deaths Now: Leads Other Cantonments With 49 During Week, Report Says."

Some people already were worried about disease leaking from these camps. Here's an item from the Jan. 1, 1918, Democrat:

Says Soldiers Spread Measles

That two discharged soldiers from Camp Pike have caused 500 cases of measles in and around Waldron, was an assertion made by W.E. Baker, editor of the Scott County Record, in a letter received by Dr. C.W. Garrison, State health officer.

Mr. Baker asked Dr. Garrison to formulate some plan whereby the civilian population in small towns and the country may be protected against the indiscriminate discharge or furlough of soldiers from Camp Pike who have contagious diseases.

Obituaries in the Democrat and the Gazette from the first two weeks of 1918 name four to eight young soldiers, every day, dead at the base hospital. That's mushy math; I'm missing several papers. But still.

The Camp Pike Gazette covered the older Army facility at Fort Roots, too. In January 1918, work began to convert the hospital that was still operating there into a general hospital that could accommodate 1,000 patients and 69 nurses. The hospital already had 275 patients, most of them from Camp Pike.

Here's an item from the Jan. 3 Gazette that's typical of the humor frequently delivered by the Camp Pike Gazette:

Communicates With Sick Via "Wireless"

All doubts of the efficiency of semaphore signaling as a method of communication have been removed from the mind of one civilian, who had the impression that the system was principally a form of light calisthenics. The visitor inquired at the receiving office at Fort Roots yesterday afternoon, asking to see a soldier friend who was in one of the innumerable wards. He was told that the soldier was in a contagious ward and could not be seen.

"How is he getting along?" the visitor asked.

"I'll find out," a sergeant said, and stepped out upon the porch.

Immediately the sergeant's's arms shot up into the air, then spread out crosswise, went through the well known Indian club motions for a minute, and came to a stop.

Across the parade ground, a figure dim in the distance rose from a chair on the porch and replied in a set of similar motions.

"He says he's all right," said the sergeant, "except he's got the toothache."

Driving past the porch from which the patient answered, the visitor stopped and talked with the soldier. "I'm sorry you have the toothache," he said.

"Who said I had the toothache?" asked the soldier.

"The sergeant at the receiving office," replied the visitor.

"He used a little too liberal a translation," answered the soldier. "I told him my jaw hurt. I've got the mumps."

Next week: Death Beats Discharge

ActiveStyle on 01/08/2018