A 51-year-old man who has served more than half his life in an Arkansas prison must be released or recharged within 30 days, a federal judge declared this week in throwing out the man's 1992 murder conviction from Dallas County.

U.S. District Judge Billy Roy Wilson, whose ruling was announced Thursday by the Midwest Innocence Project, found that John Brown was wrongfully convicted in 1992 by a Dallas County jury of the 1988 rape and murder of Myrtle Holmes, 78, in Fordyce.

Brown, who didn't live in Fordyce but was visiting relatives there when the murder occurred, has served 26 years in the Arkansas Department of Correction for his wrongful conviction on charges of aggravated robbery and first-degree murder, said Justin Scott, a spokesman for the nonprofit corporation that says it is dedicated to the investigation, litigation and exoneration of wrongfully convicted people in five states.

"No physical evidence ever connected John Brown to the crime," the project's executive director, Tricia Bushnell, said in a news release. She added, "And there was no other evidence whatsoever until investigators manufactured it. Brown was convicted based on the false confession of a vulnerable and limited co-defendant and the use of incentivized informants, whose motivations were never disclosed."

Bushnell and staff attorney Rachel Wester represented Brown, with assistance from Little Rock attorney Erin Cassinelli and interns, an investigator and students in a class taught by Bushnell and adjunct instructor Quinn O'Brien at the University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School.

John Thomas Shepherd, the current prosecuting attorney for the state's 13th Judicial Circuit, which includes Dallas County, said Thursday that he doesn't know yet if his office will retry Brown.

"I can't say right now what our plans will be," said Shepherd of El Dorado. "We need to let this situation play out."

He said he has reviewed Wilson's order, but the Arkansas attorney general's office, which has been representing the state since the Innocence Project filed a petition on Brown's behalf in late 2016, "will have some decisions to make" first.

"I plan to stay in contact with them and make sure I'm in the loop," Shepherd said.

He has been the chief prosecutor in the district for about a year, and was a deputy prosecutor the previous year, but wasn't even practicing law when the case against Brown was tried, he said.

Amanda Priest, a spokesman for Attorney General Leslie Rutledge, said later that Rutledge "is disappointed in the decision vacating John Brown's conviction for the brutal 1988 murder and robbery of Myrtle Jones" and "is currently reviewing the decision and will determine the next steps."

It took two jury trials to convict Brown and his co-defendants, Reginald Early, Charlie Vaughn and Tina Jimerson, all of whom were sentenced to life in prison.

The project said the prosecution's case "relied entirely on a now-recanted false confession from Vaughn."

Jurors in the first trial deadlocked 6-6, resulting in a mistrial being declared. In the second trial, according to the project, "critical DNA evidence was omitted that excluded Brown and Vaughn as contributors to DNA collected from the victim," and that identified Early as a potential perpetrator.

Despite DNA evidence excluding Brown from the crime scene and Vaughn's testimony that he wasn't involved in the murder and had only mentioned Brown, Jimerson and Early because he was threatened with the death penalty otherwise, Vaughn's "unreliable and confused" confession was read to the jury, the defense team said.

They said a new investigation revealed that the "confession" occurred after an informant was placed in Vaughn's jail cell, and that a recording of the conversation, which had been turned over to prosecutors, was destroyed and never turned over to the defense.

In 2015, Early gave a full confession and signed an affidavit providing details of how he had robbed, raped and murdered Holmes by himself. Then in 2016 and 2017, Early testified at Brown's and Jimerson's evidentiary hearings that he was the sole perpetrator, the Innocence Project said, noting that Brown didn't even know Early or Vaughn.

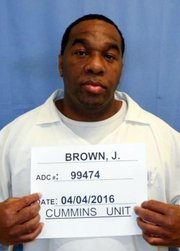

In an order signed Tuesday, Wilson granted the petition for writ of habeas corpus that the defense attorneys sought on Brown's behalf.

While adopting many of the findings that U.S. Magistrate Judge Joe Volpe made in February after reviewing the case, Wilson declined Volpe's recommendation to dismiss the petition, and declared Brown's convictions vacated.

He noted in a 26-page order that the Arkansas Supreme Court upheld the second Dallas County jury's convictions of Brown, Early and Jimerson based largely on Vaughn's pretrial "enticed confession," even though Vaughn later recanted.

"Without Mr. Vaughn's confession, it is doubtful that there was sufficient evidence to support Mr. Brown's convictions," Wilson wrote. He noted that Volpe, too, had "noted that it was troubling that law enforcement targeted Mr. Vaughn, who had significant mental deficiencies."

"By far the most important evidence -- and only direct evidence -- against Mr. Brown" was the "enticed confession of a mentally deficient co-defendant, to an undisclosed government informant or agent," Wilson said. He said evidentiary rules were violated, and it appears that the prosecution knowingly allowed a government witness to give false testimony.

"These multiple constitutional violations and irregularities seriously undermine any confidence in the outcome of this trial," Wilson said.

While Volpe found that Early's confession wasn't credible, Wilson said he considered the confession new, exculpatory evidence. He noted that it was also supported by an absence of physical evidence linking Brown to the crime despite an abundance of evidence collected at the crime scene, including hair found in both of the woman's hands and genetic material taken from under her fingernails, and several bedding and clothing items collected along with a telephone cord, a pot, a saucepan, a knife handle and two knives.

According to court documents, Holmes was found dead on Sept. 22, 1988. She had been beaten and stabbed inside her home, and her body was then placed in the trunk of her car.

"Here, the 'state's trial evidence resembles a house of cards,' built on a highly questionable confession, supported by jail-house trustees and testimony from witnesses who were so drugged out, they cannot even remember testifying in a murder trial," Wilson wrote. "The state's failure to disclose the use of an informant to entice the confession is sufficient, alone, to undermine confidence in the verdict. But this was not its only failure. The state also failed to disclose, and actually destroyed, a recording of the informant eliciting the confession."

Wilson wrote that Robin Wynne, who was then a deputy prosecuting attorney on the case and is now an associate Arkansas Supreme Court justice, "may be able to shed light on the exculpatory value of the recording," but didn't testify during evidentiary hearings last year before Volpe and U.S. Magistrate Judge Jerome Kearney. In a footnote, he said he recognizes how "uncomfortable it would be" to call Wynne to testify about "alleged, decades-old, prosecutorial misconduct."

Since Early's confession, separate teams of defense attorneys have been working to clear the convictions of Vaughn and Jimerson, according to Scott of the Midwest Innocence Project. He said those petitions are still pending.

Metro on 08/24/2018