FAYETTEVILLE -- Women who enroll at the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville as freshmen have a higher graduation rate than men, with the most recent yearly data showing a gap of 9.5 percentage points.

It's the largest gender difference at UA going back at least 13 years, the time period for which federal data are published online by the National Center for Education Statistics.

But if there are lessons to be learned from the achievement gap, common at many colleges and universities, they extend far beyond campus borders, experts said.

"Universities alone aren't going to solve the problem," said Nancy Niemi, director of faculty teaching initiatives at Yale's Center for Teaching and Learning and the author of a book on different outcomes for women and men in higher education.

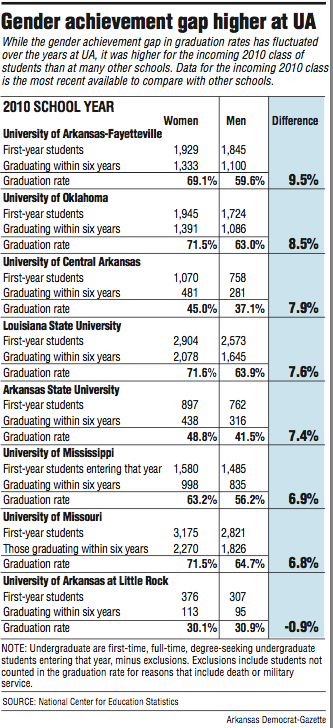

UA's graduation rate gap for students entering in 2010 was the highest among the five largest Arkansas universities by undergraduate enrollment. The university's six-year graduation rate for women was 69.1 percent compared with 59.6 percent for men, based on federal data.

Nationally, for students first enrolling in 2009, the six-year graduation rate was 62 percent for women and 56 percent for men, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, for a gender achievement gap of 6 percentage points. The most recent published data on national graduation rates are for the group of students entering in 2009.

With more women enrolling than men -- also a national trend -- women earned more UA bachelor's degrees than men.

For male students, 1,100 earned UA degrees within six years, out of a group of 1,845 who enrolled in 2010 and count toward the graduation rate. A total of 1,333 women earned degrees out of 1,929 enrollees, according to federal data.

At UA, the strongest explanation for the gap in achievement goes back to high school, said Gary Gunderman, UA's executive director of institutional research and assessment.

He said the university keeps track of various factors to help identify what makes students more at risk of dropping out, looking at their socioeconomic status and whether they are the first in their family to attend college, for example.

"That [gender] gap, when you look at it, the biggest part of it is simply accounted for in their high school GPA," Gunderman said.

Far from a one-year blip, Gunderman said, data going back to incoming students in 1998 consistently show women arriving, on average, with better high school grades than their male counterparts.

When it comes to incoming students' success in college, high school GPA "is the best predictor that we have," Gunderman said. Chancellor Joe Steinmetz in September said unmet financial need is as big a factor in student retention as "pre-college academic readiness."

After accounting for high school performance, gender differences remain but are slight, Gunderman said.

"If we have a male with a 3.5 high school GPA and a female with a 3.4 GPA, then that male is more likely to graduate within six years," Gunderman said.

More than half of first-year female students in 2016-17 participated in sororities, with the percentage generally growing in recent years, according to information provided by UA in its Common Data Set survey. Gunderman said he has not studied academic differences for those participating in sororities or fraternities.

It's a different story when it comes to scores on college entrance exams, he said.

"The average male's ACT is higher than the average female's, despite this [grade-point] gap," Gunderman said.

While the gender achievement gap has reached a peak, Gunderman described the gap as fluctuating over the years. Federal data show the gender difference in graduation rates to be roughly 6.6 percentage points on average, going back to the class of students who first enrolled in 1998.

Both men and women have seen graduation rates increase. UA in November 2016 reported its highest graduation rate ever, at 64.5 percent. Some peer schools reported higher graduation rates, including the University of Missouri, which reported a six-year graduation rate of 68 percent, and the University of Oklahoma, which reported a six-year rate of 67.5 percent.

Gunderman said an updated graduation rate for students who entered in 2011 will likely be released this week.

To boost student success, Gunderman said, the university offers free tutoring, supplemental instruction and academic counseling. The university helps at-risk students, but it's underlying factors like a low high school grade-point average, rather than gender, that drives that support, Gunderman said.

Niemi, author of Degrees of Difference: Women, Men, and the Value of Higher Education, said cultural norms rather than any innate differences help explain the educational achievement gap.

"There's a long-standing cultural message that women play better in school," Niemi said, describing the kinds of actions required in the classroom, like sitting down, paying attention to the teacher and behaving appropriately. "Doing the kinds of things school requires are something that women will do more than men."

Men are not often "socialized to be as compliant," while another factor may be an unwillingness "to accept deferred gratification," Niemi said, noting the growing length of time it takes to earn a college degree.

A report last year from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center found that it takes, on average, 5.1 years for students to earn a bachelor's degree. The report also cited evidence that the amount of time for most students has increased over the past 30 years.

Niemi said women continue to struggle with inequality in the workforce, with cultural factors undercutting them economically. "School is just one piece of it," she said.

She said she did not think universities should single out men for special help but said schools can do a better job of communicating the value of a college education in ways that all students will appreciate.

"Men, in particular, look at the ways in which completing their degree will help them get more fulfilling jobs, higher-paying jobs," Niemi said.

In the classroom, good teaching should actively engage students, but "a lot of college professors don't teach that way," Niemi said.

In Arkansas, the state badly needs to improve the outcomes for students in higher education, said Sarah Beth Estes, a sociology professor at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock who has studied gender differences.

"We are at the bottom of educational attainment across this country, and that is terrible for our state," said Estes, who leads the UALR Office of Community and Career Engagement.

She said that while a greater share of women are earning degrees, there remains a gap between women and men in many technology fields.

"There's a lot of the labor market that's sex-segregated," Estes said, calling for stronger support for all youths interested in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, or STEM, fields.

"To really work, we have to do it far earlier than college. We need to be working with young people all through the pipeline, starting early in their education to engage them with STEM," Estes said.

A Section on 11/06/2017