The cost of housing is a growing burden for tens of thousands of lower-income families in Northwest Arkansas cities, leaving many of them stuck with high bills, shoddy housing, even homelessness.

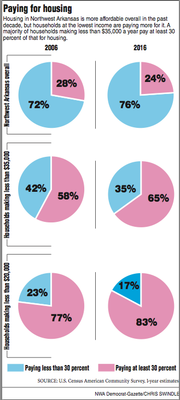

Two in three households making less than $35,000 a year pay more than 30 percent of that income for homes or apartments, a conventional definition of unaffordable housing used by federal agencies. That included almost 38,000 households last year, according to Census estimates for the Fayetteville-Springdale- Rogers metropolitan area.

The picture is grimmer among households making less than $20,000, such as single adults working a full-time minimum wage job or many drawing Social Security benefits. More than 80 percent of them are above the 30 percent spending line.

The housing price situation is a paradoxical one, because Northwest Arkansans overall are spending less on housing. About 24 percent were in unaffordable accommodations last year, down 4 percentage points from a decade earlier. Arkansas in general is one of the most affordable places to rent an apartment in the country, the Washington, D.C.-based National Low Income Housing Coalition found this year.

Housing costs are a more intense problem only for those with fewer resources to help.

The group includes Robin Brooks, 63, who lives alone in her west Fayetteville home after moving there to take care of her father until he died a few years ago. She said she gets Social Security payments and can’t work because of a disease that can ruin the body’s ability to keep its balance. Without her father’s income, Brooks couldn’t buy enough food at the end of the month after bills and a mortgage payment around $500, even after selling his old car.

On top of that, the house’s air compressor stopped working around August, and Brooks feared she’d have to face the approaching winter without heat.

“I was just stuck here,” she said in an interview this month.

She applied to Fayetteville’s Community Development Program, which used part of a federal grant to find the problem — a furnace installed wrongly back in 1996 — and replaced it without charge. The program helps about 10 low- and moderate-income homeowners each year make such repairs and keep aging houses habitable.

Brooks said the work would have cost her thousands of dollars and trimmed up to $40 off her monthly utility bill. She called the service a miracle and praised the contractors and city employees for their compassion and quick work.

“I have this big grin on my face just talking about it,” she said.

Burdensome costs are particularly widespread in Fayetteville, where more than a third of the city’s households and nearly all of those making $20,000 or less fall into the unaffordable category. Bentonville has 20 percent of households in that situation. Rogers and Springdale fall in between.

RISING MARKET

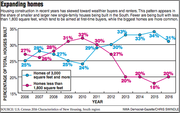

New housing construction in recent years has been skewed toward higher earners as homeownership rates drop and the region prospers and attracts well-paid professionals, based on data from the real estate firm CBRE, developers and the University of Arkansas, Fayetteville.

CBRE’s regular report on the apartment market for the first half of this year counted about 3,000 new apartment units built since 2013 in the four main cities. Two-thirds of those units cost more than average rent of about $700 in the cities. Many are renting for $1,000 or $2,000 a month.

Houses sold in Benton and Washington counties have surged in their average price in the past few years as well to make up for ground lost in the recession. The average sale topped $220,000 this year, up about 37 percent from 2011, according to the latest Skyline Report from Arvest Bank and the university’s Center for Business and Economic Research.

The average value of building permits for new homes, which gives a general measure of how much those new homes will cost, was around $300,000 in Bentonville, Fayetteville, Rogers and Springdale.

Developers and real estate agents say the rising costs for labor, materials and land make it hard to build at a bargain.

Some recent land purchases make plain the increasing cost of acreage. THRIVE Bentonville, a high-end apartment complex built near the city square, stands on 0.7 acre the developer bought for $231,000 in 2013, more than five times its price in 2002.

“That really does determine, ultimately, the rents that we need to charge,” said Sarah King, a spokeswoman for Specialized Real Estate Group. The company’s properties include the Uptown Fayetteville complex, where rents for one bedroom range from around $800 to more than $1,400. Its 7.6 acres sold in 2015 for more than $3 million.

The slant toward better-off residents is common around the country, researchers at Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies wrote in their State of Nation’s Housing report this year. Fewer starter homes for first-time buyers are being built and rents are rising faster than incomes, the report found. Poorer families are drifting to the fringes of urban areas for cheaper options farther from many jobs and services.

Apartment List Rentonomics, which tracks the apartment market nationwide, said in a report released this month that the number of rental stock for rents lower than $800 fell by more than 1 million units from 2005 to 2016 even as several million new apartments were built.

“We’ve got higher construction costs than we’ve ever seen, higher land costs than we’ve ever seen, and more people moving here than we’ve ever seen,” said Casey Kleinhenz, property manager for a nonprofit affordable housing developer called Community Development Corp. of Benton-ville and Bella Vista. “That’s what’s so unique right now.”

Meanwhile, directors of public housing authorities in Fayetteville, Springdale and Siloam Springs report their 600 units are full and have waiting lists ranging from several months to two years. Nonprofit groups dealing with homelessness often say housing prices are a common reason for people to be on the streets and in shelters.

Jeremy Collins said he’s one of half a dozen people couch-surfing at a single house in Fayetteville. His disability benefits total about $750 a month, which wasn’t enough to cover food, bills and a rent of $575 and left him alternating between friends’ homes and camping in the woods.

“It’s hard to find a place,” Collins said last month at Genesis Church, whose members are trying to help him find an apartment that will accept him and his girlfriend despite their nonexistent credit.

AGAINST THE TIDE

Several developers say they’re working around these obstacles to provide quality, lower-cost choices. Some take the nonprofit group route. Fayetteville’s nonprofit Partners for Better Housing plans to begin construction on its first subdivision in earnest next year, for example, board chairman Keaton Smith said.

For-profit Rausch Coleman Homes builds in Arkansas and other states and gears its houses toward first-time buyers with mortgages often less expensive than rent, division sales manager Lance Drinkard said earlier this month. He spoke in one of the dozens of one-story houses being built near Northwest Arkansas Regional Airport. Workers outside cut brick and assembled frames while rolls of sod the size of hay bales waited for unfurling.

The company buys materials in bulk, builds a lot and is willing to do with less profit, Drinkard said. Many of its houses are available with no or low down payments, and all come with 10-year structural warranties.

“It takes a lot of discipline,” Drinkard said. “It works well for us.”

Laci Rogers, her husband, Jeremy, and their 2-year-old, Ayla, moved into one of the homes in November after buying it in June, she said. A comfortable four-bedroom house ran them about $128,000 and replaced the old, cramped mobile home they had in Bella Vista. Most of the other homes they found around that price were very small or needed a lot of work, she said.

Now she can be a stay-at-home mom while her husband works at the Wal-Mart office nearby. The family also will be able to join the foster system after their previous housing didn’t pass its requirements.

“It is very, very exciting,” Rogers said.

Building farther away from the region’s urban center can be helpful when it comes to prices; home building permits outside of the four biggest cities are valued at about $84,000 less on average, according to the Skyline report. But this pattern varies by location; permits in the first half of 2017 hit their highest value of more than $500,000 in Johnson and topped $440,000 in Little Flock. Drinkard said Rausch’s model can bring low costs even in the big cities as well.

Rogers real estate investor John Schmelzle said the dearth of building at lower prices leaves that market wide open even in urban areas. He and a Fort Smith builder are partnering to build 128 units in Rogers starting at $650 for one bedroom.

Lindsey Management lists some 12,000 apartments in Benton and Washington counties on its website and charges rent as low as about $400 in some locations. It’s expected to build another 600 in Bentonville in the next year, according to CBRE. A spokesman didn’t answer several emailed questions this month about how and why the company keeps its prices where they are.

Other builders use federal support, such as the Low Income Housing Tax Credit. The program helps lower construction costs by giving builders credits that investors can buy to lower their own tax bills, leaving the builders with the cash. Joining the projects, either as the credit buyer or as a lender to help the project keep moving, can help banks meet legal requirements for investment in local communities, said Paula Wilson, senior vice president and commercial loan manager at Arvest Bank.

Builders must in turn offer some of their units with below-market rates that won’t cross the 30 percent threshold for low-income tenants. The Arkansas Development Finance Authority distributed more than $7 million in credits this year to build or rehabilitate about 500 units, according to its online records. Nearly all of the units were designated for low-income tenants.

About $2.7 million went to five projects in Benton and Washington counties, including 40 apartments near Wedington Drive in Fayetteville and 30 senior apartments in Rogers that are all being built by Mountain Home-based Leisure Homes Corporation. The company garnered millions of dollars in credits in the past decade.

Leisure owner Tom Embach Sr. said the projects would be impossible without the credits, which cover a majority of the costs. Otherwise he said he’d have to build smaller or lower-quality housing to offer the same low rent.

Many potential projects don’t get federal money, including the Fayetteville Housing Authority’s proposal this year to build almost 60 apartments in south Fayetteville for dozens of its tenants. Ben Van Kleef, vice president of the legal and tax division at the state finance authority, said the agency receives about three times as many requests as it can meet.

The state’s available tax credits have fallen to below 2007 levels after surging during the recession. Nationally, the credits plunged after the recession to a level about even with 2007, according to data from the National Council of State Housing Agencies, which compiles data from every state.

Federal housing support is slipping in other ways, local officials said. The Fayetteville authority’s federal money for capital improvements has fallen by half since 2008, for instance. The Siloam Springs authority, which covers all of Benton County, is authorized to provide 513 families with housing vouchers they can use to lower rents at accepting apartments but gets money for only 390, director Judy Hobbs said. The waiting list for them lasts more than 16 months.

“We can’t help as many people as we used to, and I don’t know what the answer is there,” Hobbs said.

Arkansas’ two senators declined to answer questions about their stance on federal housing policy and financial support. A spokeswoman for Rep. Steve Womack of Rogers didn’t respond to an email request this month.

LOCAL STEPS

Northwest Arkansas governments and groups have taken some steps to make lower-cost housing easier to build. The Rogers City Council in November adopted standards for tiny houses to be allowed in some parts of the city, for example. Rogers community development director John McCurdy said the change is part of a broad review of city codes affecting development density.

Fayetteville and other cities have long made a priority of encouraging infill of unused land. Fayetteville officials have made zoning changes along busy College Avenue in recent weeks to encourage that kind of development.

Mervin Jebaraj, economist and director of the University of Arkansas’ Center for Business and Economic Research, tracks the region’s economic picture and has said rezoning urban land to allow housing and more of it per acre could help address the price issue without shunting low-income families to far-flung locations. With retail shifting online, land that’s used for big box stores and their parking lots could work well, he said in October.

“When there’s a scarcity of land, that encourages builders to build for the highest income,” he said. “And I guess it is an artificial scarcity.”

King, the Specialized spokeswoman, said higher density would “absolutely” allow more affordable rents.

“As downtowns become desirable, we see lower income people, lower income families pushed to the margins of our community,” she said. “That’s a really terrible place to be, because you’re isolated from infrastructure, from services, from mass transportation.”

The university’s Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design this month announced the Walton Family Foundation gave $250,000 to sponsor a design competition and symposium aiming to promote attainable housing. The foundation earlier this year also gave $120,000 to the nonprofit Community Design Corp. to come up with freely available designs for auxiliary dwelling units, smaller houses that can be built in backyards and rented out, Kleinhenz said.

The foundation’s home region program director, Karen Minkel, said it hopes to ease housing prices in downtown areas in particular and try to head off the kind of housing crises affecting other vibrant metros. The foundation is in the early steps of this effort, she said.

Northwest Arkansas needs more, more, more of this type of work, whatever it takes to lessen the housing crunch for the lowest income levels, said Sister Lisa Atkins with Mercy Northwest Arkansas. She has helped lead homeless assistance efforts with the health system.

“We need more affordable housing, more truly affordable housing,” she said. “We’re all children of God. We all deserve dignity.”

Dan Holtmeyer can be reached at [email protected] and on Twitter @NWADanH.