First-responders are worried an increasing number of psychiatric calls in Northwest Arkansas will tax emergency resources.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

Last year, 11,383 Arkansans called the suicide prevention hotline for help. That number increased to 11,633 this year through the end of October. The hotline is a free, around-the-clock support network for people who have suicidal thoughts. The number is 800-273-TALK (8255).

Source: Arkansas Department of Health

“We’re all like: ‘What are we going to do?’” said Jim Vaughan, division chief at the Springdale Fire Department. “It’s become the biggest change recognized [among emergency departments] in the last five years.”

Agencies are handling more low-risk psychiatric calls, which often are threats of self-harm or suicide and family members calling 911 because they are worried loved ones are going to hurt themselves.

Springdale police went to 15 percent more suicide calls last year than the year before, according to city records. Fayetteville and Springdale police often go to suicide-related calls without fire departments or ambulance service, according to firefighters from both agencies.

Still, firefighters are responding to a large share of those behavioral-type calls, they said.

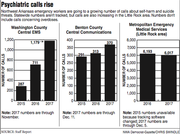

Rogers paramedics and emergency medical technicians will likely respond to 700 such calls by the end of this year, Fire Chief Tom Jenkins said. That’s up from about 545 such calls last year, and 134 in 2009.

Springdale, which runs its own ambulance service and discontinued service to several small cities last year, cut about 1,500 emergency calls overall. But, that didn’t greatly reduce the number of psychiatric calls, Vaughan said.

Springdale firefighters went to 648 behavioral and psychiatric calls in 2015. The number declined to 632 in 2016, records show.

Psychiatric call volumes aren’t tracked statewide, but emergency officials in various counties have told state officials about increases, said James Bledsoe, EMS and trauma medical director at the Arkansas Department of Health.

The increases affect workloads and force agencies to stretch resources, law enforcement and emergency officials said. If paramedics and law enforcement are going to low-risk calls, they aren’t available to handle other emergencies, officials said.

RISING WORKLOAD

Emergency workers often arrive at a home and find no one is physically injured.

Rural fire departments stopped responding to low-risk suicide calls in August as part of a pilot program. Volunteers were responding to calls when about half or more were canceled en route or where volunteers never saw a patient, fire chiefs said. Between August and October, about half the calls the departments would have gone to were canceled on the way, according to Central Emergency Medical Services figures.

The program will be evaluated next year to see whether rural fire departments should attend those calls.

The Northwest Arkansas trend of more psychiatric calls coming in is similar in Little Rock, where Metropolitan Emergency Medical Services went to 6,017 psychiatric calls, of which 2,198, or 35 percent, didn’t go to a hospital.

Vaughan said Springdale ambulances go to at least one each day. The Washington County Sheriff’s Office reported suicide threats jumped 29 percent from 2014 to 2016.

About 27 percent of Central EMS’s call volume is listed as a minor emergency, which includes suicide threats. In Rogers, low-risk psychiatric calls make up about 15 percent of the total per year, Jenkins said.

“They are a pretty significant chunk of the emergency responses,” he said.

Eventually, the emergency system is going to be stressed, ambulance and law enforcement officials said.

Of the roughly 220 ambulance services in Arkansas, eight are in Benton County and two in Washington County.

“We do have finite resources,” Central EMS Chief Becky Stewart said.

Ambulances will always respond, Stewart and others said, but agencies, including Fayetteville Fire Department, aren’t going to all calls.

On top of that, even if the person is in a mental crisis, there’s little emergency workers can do to help them, Jenkins and others said. Police and ambulance workers take the person to an emergency room, they said.

“The ambulance service is basically becoming a taxi service,” Jenkins said.

Partly, the problem is exacerbated by the increase overall in calls, officials said.

Total emergency calls to Central EMS rose 11 percent to 21,056 in 2016 from 2015, according to an annual report. The increase includes Central EMS acquiring some parts of Washington County from Springdale, but the service is on track to outpace that number by the end of December, according to Central EMS records.

The increase is happening despite Stewart ending a wheelchair transportation service this year.

LACK OF SERVICES

More people are asking for help by calling 911, state and local emergency officials say.

“People are driven in that direction by their clinicians,” said Justin Hunt, chief medical officer and senior vice president at Ozark Guidance, a private, nonprofit mental health center in Northwest Arkansas.

Callers are often young, depressed, addicted to alcohol or drugs or ostracized from their families, said Gene Page, Bentonville Police Department spokesman. Once they call for help, there are few places to take them, Page said.

“These people are just bounced around without any help,” Page said. “Mental health needs are just not being met.”

Northwest Medical Center-Springdale is the only acute-care hospital with adult behavioral-health inpatient services in Northwest Arkansas, said Christina Bull, spokeswoman for the hospital. The hospital is adding 14 beds for acute care and four medical-psychiatric beds to its 29-bed mental health unit, Bull said in email.

Construction is expected to be completed in early 2018.

Washington County is putting together a state-funded crisis stabilization unit to handle people who are in a mental health crisis, but that unit will be focused on diverting people from jails, said Hunt said.

Northwest Medical Center-Springdale has agreed to provide free space for the unit. Ozark Guidance also is involved with the project.

The roughly 16-bed unit will be one of four units to open in counties chosen to participate in the pilot, diversion program. The other counties are Sebastian, Craighead and Pulaski.

Emergency officials say it’s not enough.

“We see some folks repeatedly. We know they aren’t getting the long-term help they need,” Stewart said. “We know what we are doing is helping them get through the moment, but it’s just a Band-Aid on a bigger problem.”

Arkansas has the 10th highest suicide rate in the nation. Suicide is the second leading cause of death among people ages 25 to 34, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

“Suicide risk touches on every big issue in society,” Hunt said. “There’s no exact way to explain this.”

A combination of factors are driving up suicide calls, Hunt said. Those include addiction, population growth and a growing awareness about mental or mood disorders in general, state officials said.

The state rolled out a large-scale public outreach and educational campaign this year and plans to open a call center in Arkansas as part of the National Suicide Prevention hotline by the end of the month, said Mandy Thomas with the state Suicide Prevention Program. Education is part of the solution, she said.

That education should include when to call 911 versus the hotline so emergency systems are not overloaded, Bledsoe said. Until then, firefighters, law enforcement and ambulance services are picking up the slack for social problems, Jenkins said.

“There is no good solution,” he said.

Scarlet Sims can be reached by email at [email protected] or on Twitter @NWAScarlets.