I am just old enough for the name Lowell Thomas to have some resonance.

I admit I sometimes confuse him with the old Timex watches spokesman John Cameron Swayze, but I remember the mellifluous artifice of his precisely enunciated announcer's baritone; the Midwestern/mid-Atlantic newsreel style influenced broadcast professionals from Tom Brokaw to Ted Baxter. Is it the voice of America? Maybe. If there has to be just one it might as well be one of disembodied, vaguely folksy authority.

Thomas was a pioneer in self-promotion and branding, employing his signature sign-on ("Good evening, everybody") and sign-off ("So long, until tomorrow") through his 46-year radio career (ending in 1976). He used those catch-phrases as the titles of his autobiographies, one of which -- So Long Until Tomorrow -- I read when it was published in 1977. I don't remember much about it, other than Thomas got remarried in the 1980s, and that he turned down the Shah of Iran's offer to be married in Persepolis.

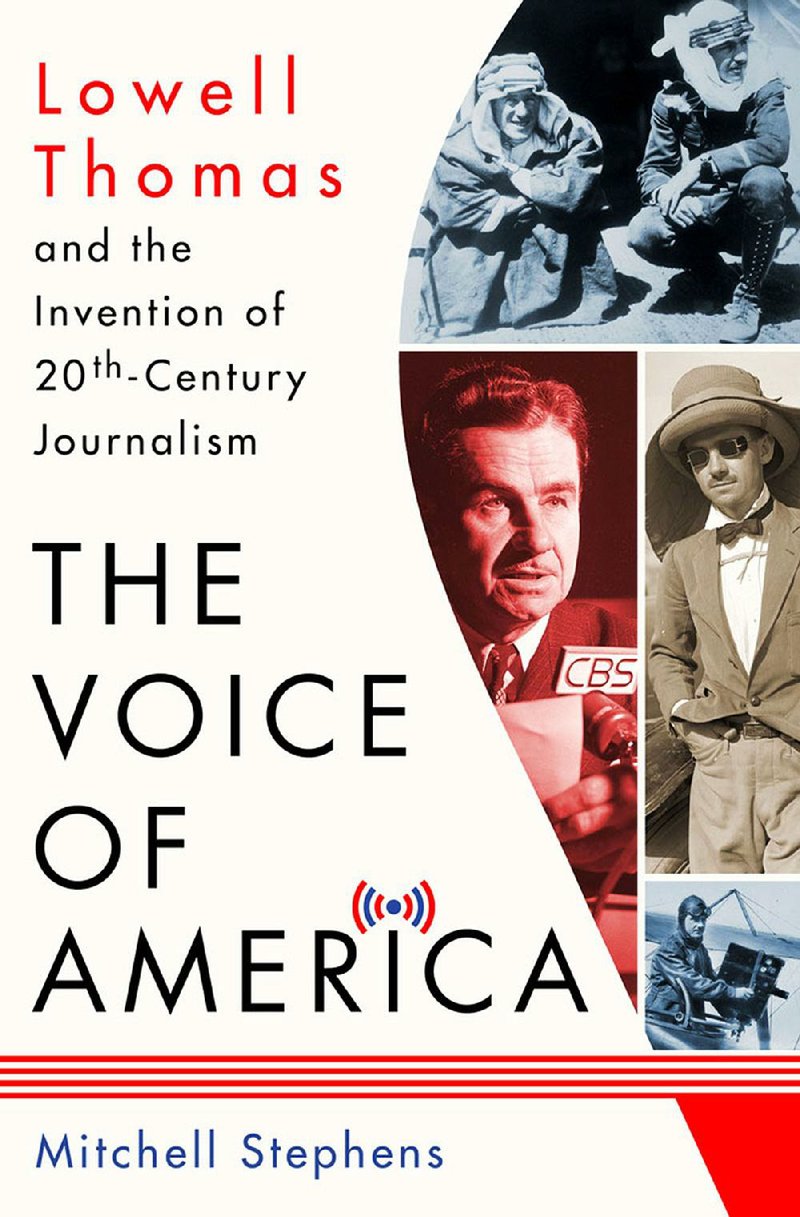

But I hadn't really thought much about Thomas since then. Before reading New York University professor Mitchell Stephens' new book, The Voice of America: Lowell Thomas and the Invention of 20th-Century Journalism (St. Martin's Press, $26.99), it had been decades since I thought of Thomas.

Born in Ohio, the son of a doctor and a schoolteacher, Thomas spent his formative years in Colorado, where he worked as a gold miner, a cook and a newspaper reporter before graduating from high school in 1911 and beginning a peripatetic career that had him racking up academic credentials at an impressive speed -- in 1912 and 1913 he received three undergraduate degrees and a master's from two different universities -- finally landing for a while on the staff of the Chicago Journal. (At the same time he was a lecturer -- on oratory -- at the Chicago-Kent School of Law.) In 1914, he moved on to Princeton University, where he completed work on another master of arts degree.

He was a brash and confident young man -- he spent a few weeks in Alaska filming a travelogue and thereafter held himself out as an expert on the region. He basically assigned himself to cover World War I, enlisting the help of cameraman Harry Chase. They traipsed around the Western Front and Italy, finding little they thought would excite the folks back home. But in February 1918, Thomas and Chase went to Palestine, and in Jerusalem they met T.E. Lawrence, a captain in the British army who was working to foment a rebellion against the Turks. Thomas took one look at the dashing Englishman, clad in the robes of a Bedouin sheik, and understood he had hit upon his story.

Thomas eventually returned home, where he embarked on a tour with his elaborate multimedia presentation With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia, which featured 30 short films and 285 photographic slides. It was hugely successful, both in the U.S. and in London, and while Thomas took pains to remind his audience that it was "not in any sense an historical account" but rather a subjective tour of the Holy Land, it effectively minted a persistent myth many still take as factual.

"The dozens of biographers of T.E. Lawrence disagree on the extent of Lawrence's own responsibility for inflating his accomplishments and creating the legend of 'Lawrence of Arabia,'" Stephens writes. "But it is apparent even from Thomas' initial efforts to record Lawrence's story ... that Lawrence ... contributed quite a bit to that legend. But if 'Lawrence of Arabia' was half-invented, Lowell Thomas must share credit for the invention ...."

Stephens devotes only two chapters to the Lawrence business, but there's a sense that the rest of Thomas' long and vivid -- and successful -- life was simple epilogue. His Lawrence story set him on a trajectory that took him around the world and made his voice familiar to every American. Thomas interviewed the 14-year-old Dalai Lama in Tibet after China went communist; he anchored the first live telecast of a political convention (the Republican National Convention of 1940, which was held in Philadelphia, though Thomas broadcast from New York). In the 1970s, he hosted a travelogue series on PBS.

Stephens does a good job in setting out the facts of Thomas' oversized life, and while he betrays his affection for his subject, he never slips into hagiography. It's clear the author has some sentimental attachment to the boisterous journalism practiced in the early part of the 20th century, when figures like Thomas and H.L. Mencken weren't above improving their stories.

It's tempting to see Thomas as a product of his time, but I'm not sure he wouldn't thrive in the age of Twitter.

In the 1920s and '30s, Thomas was as famous as Babe Ruth and Clark Gable. Given how long he out-lived those icons, it's mildly surprising that he seems so obscure today. But then radio, his primary medium, is a more evanescent form than the movies, and other broadcast journalists -- Edward R. Murrow, Walter Cronkite, even Walter Winchell -- figure more prominently in American mythology. Stephens' book is purported to be the first serious book-length biography of Thomas, and that in itself would be enough to justify it's existence.

That it's a lively read is a bonus.

Email:

Style on 08/20/2017