Do you know people named Fletcher? More than several? Fletcher has been an Arkansas name since at least 1825, when an American revolutionary matross of that surname was laid to rest in Randolph County.

John Fletchers in particular were prominent in the pages of the 19th- and 20th-century Arkansas Gazette, when several were lawyers married to civic-minded women.

Today's database of registered voters includes 1,083 Arkansans with the last name Fletcher. And Fletcher is the first name of 59 voters, whose last names, as it happens, are not Fletcher. We have no voters named Fletcher Fletcher.

For 119 voters, their middle initial F stands for Fletcher.

Imagine the crowd of ancestral Fletchers piling up on U.S. Census lists and genealogy websites. Say you wanted to learn about one John Fletcher, one who left Arkansas to go to war in France in 1917. He was born in 1895; his middle initial was P; his father was a sheriff in Lonoke County for a few years and named Thomas.

John P. wrote an interesting letter to Thomas that the Gazette published on its front page 100 years ago Wednesday.

The paper had first mentioned John P. in 1913, after he won one of "the high school contests" in Lonoke. He won for "debating"; other students won for mechanical drawing and piano.

Two months later, he and Aetna Felton, Lee Koonce, Oma Harrell, Jesse Goodbar and Bessie Mae Trimble were the 1913 graduating class of Lonoke High School:

The large auditorium, with all the classrooms thrown open, was decorated.

OK, then. Next word we have of him comes from the June 7, 1917, Gazette:

John P. Fletcher, son of former Sheriff Tom Fletcher of Lonoke, was in Little Rock yesterday. Mr. Fletcher formerly was a reporter on the Gazette's staff, but for the past year has been studying at the School of Journalism of the University of Missouri. He left for Lonoke yesterday to spend two weeks with his parents and then will go to St. Louis to join the University of Missouri Ambulance Corps. The corps will sail soon for France. The university unit was organized by Virgil Beck, also an Arkansan, who lived at Texarkana and was a student at the School of Journalism. He also will go with it.

The unit included 25 MU collegians and their instructors.

Unreported was the fact that John P. had engaged himself to Miss Helen Hale of Springfield, Mo. She was a niece of A.J. Allen of Little Rock, but they'd met while John P. was reporting for the Joplin [Mo.] Globe in 1915.

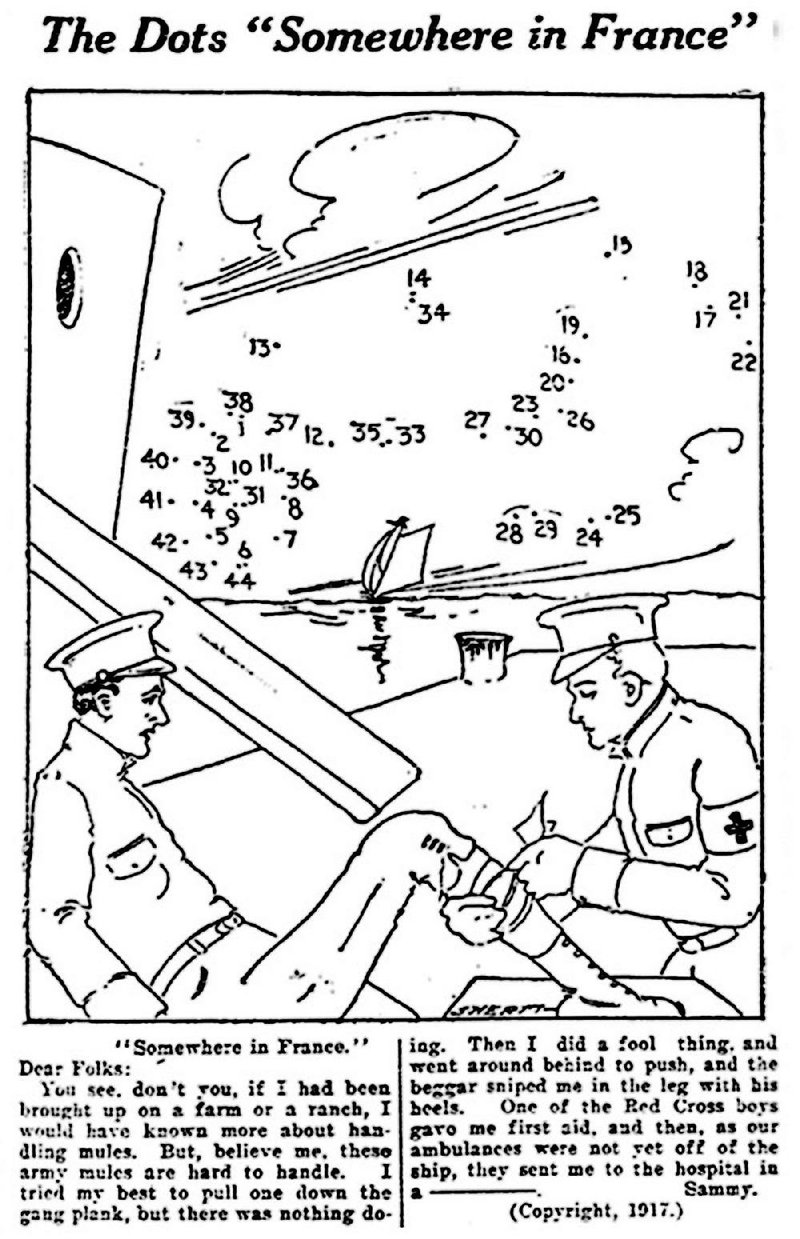

Aug. 15, 1917, the Gazette published that letter from 22-year-old John P. to his father:

He Testifies to German Brutality

"Dear Dad: We will leave here (somewhere in France) for active service Friday, July 20, according to our French lieutenant, who thinks we are about the finest bunch of boys he ever saw. We can't get out too soon to suit us, of course, although all of us like the training camp and the men in charge. 'We' does not include all the men in camp, of course, only the M.U. unit. Our place will be taken here by new men, and we will proceed immediately to our headquarters, which will be even nearer the active front than the training camps. We will lose our identity as an individual unit, I am afraid, for we were told we will join the Dartmouth unit. ...

"We have had some wonderful drives during the past week in our practice road work. ... I saw a village of 600 inhabitants that had been the center of one of the longest, hardest-fought and most important battles of the entire war, and in which many thousands of men were killed. Not a wall or a 20-yard stretch of stone fence was intact. There was not a roof left, and great holes had been torn in the ground by big shells. Only the streets had been cleared and repaired, for military purposes. Trenches and barbed wire entanglements ran riot around the village -- some of them were German, some were French and some were English. We spent two hours in the vicinity, and went through a number of trenches of both sides. Of course no one lived in or near the village, and one can't imagine a more desolate spot.

"Before they fell back the Germans even destroyed the tombstones in the little village cemetery. ...

"I have also seen several cathedrals that were used as pointers by the German artillery. Usually the spires are blown off, and sometimes the church proper has been hit and almost demolished. At one little town they still hold services in a cathedral that has no spire, and it is minus an immense section of roof and wall. Rain and snow blow through the opening, but not a service has been missed yet, a villager who speaks English told me. The inhabitants of the village live in mighty danger of being bombed, but they always are cheerful, and always have a smile and a word of cheer for an American.

Would Make Men Fight

"I don't want you to think I am letting my enthusiasm run away with me, but if every young American could see what I have of the suffering of these villagers, and the wanton cruelty and brutishness of the German invaders, Uncle Sam couldn't find means to train and transport the men who would fight each other for a chance to be the first to get over here with a Springfield and mess kit. For I am confident that all of them would feel their gorge rising until they began to see red, and grit their teeth and damn the Germans, whose utter depravity and lust have laid waste to so beautiful a bit of the world, and killed so many thousands of absolutely harmless women and children. If I were home now I couldn't get into the army too soon to suit me. As it is I am very glad that it will be ammunition our unit will carry to the front for the French fighting men."

...

A member of the American Field Service, John P. drove an ambulance for the French army through October. In May 1918, the Gazette reported he had seen the fiercest of fighting. He survived unscathed, but his wedding announcement, published April 18, 1919, after he was safely back at home, suggests one very lucky Fletcher:

He, with three American companions, was awarded the Croix de Guerre for going up to the front line on the night of June 12, 1918, with an ambulance and returning with five seriously wounded soldiers through a rain of artillery shells and machine gun bullets.

A photo of the groom in uniform appeared beside the announcement, under the headline "Croix de Guerre Man Becomes a Benedict" -- that is, a confirmed bachelor turned newlywed.

Mr. and Mrs. Fletcher moved to Missouri, where they gave the world two more Fletchers.

In 1949, a John P. Fletcher of St. Louis sent $10 to the editors of Life magazine, proposing a fund to help a former soldier who was hospitalized with tuberculosis in New York and his Austrian war bride bring their 2-year-old daughter, Jeanette Markunas, home from Vienna. (Look that up, it's a sweet story.)

In 1961, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that Fletcher was retiring from its news copy desk after 27 years with the paper. He was a licensed real estate broker and planned to go into business with wife Helen.

On Oct. 9, 1968, his obituary in the Post-Dispatch mentioned long service to his local newspaper union. He was 73.

John P. and Helen Fletcher are buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Kirkwood, Mo. But if you search Arkansas for other John Fletchers, I predict you will find at least 10.

To reach Celia, take aim at

ActiveStyle on 08/14/2017