Tuesday will mark the 75th anniversary of the Doolittle Raid, a daring bombing attack upon five Japanese cities that occurred April 18, 1942. Eighty volunteer airmen flying 16 B-25 bombers, led by legendary aviator Lt. Col James H. "Jimmy" Doolittle, took off from the deck of the carrier USS Hornet early that morning and struck back at Japan in retaliation for the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Navy on Dec. 7, 1941.

Today only one member of the Doolittle Raiders remains, 101-year-old Lt. Col. Richard E. Cole, Doolittle's co-pilot. On Tuesday at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force (NMUSAF) in Dayton, Ohio, in a private ceremony that has become famous in the annals of modern aviation, Cole will turn over the silver goblet of my late father, S. Sgt. David J. Thatcher, the second-to-last surviving member of the Doolittle Raid, who passed away on June 22, 2016, at the age of 94, and make one final toast to all the Raiders who have preceded him before drinking for the last time from his standing silver goblet.

The passage of time has taken its toll on the Raiders who, like so many other members of the Greatest Generation, stepped up during a period of world crisis to save democracy and the United States. Of the 61 Raiders who survived the Raid and World War II, accidents, disease, age

and finally death have carried all but one into the afterlife. But the memory of their daring action lives on.

Of the 80 Raiders who bombed Japan, three were killed after exiting their aircraft on the night of the Raid. Eight were captured by the Japanese; three of those were executed on Oct. 15, 1942, one starved to death, and four were held captive for 40 months including long-time Camden resident Lt. Col. Robert L. Hite. Ten were killed in action in Europe, North Africa and Indo-China, and two were killed in plane crashes in 1942 in the U.S.

In the four months after Pearl Harbor, the world was crumbling. The war in Europe had been raging for two years. A significant portion of the U.S. Pacific Fleet sat at the bottom of Pearl Harbor and the Japanese seemed unstoppable, seizing victory after victory in the Far East. In the U.S., morale was sinking and Americans were grasping for any good news.

Tasked with striking back at Japan for the attack on Pearl Harbor by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Doolittle selected a band of gritty volunteers to accomplish the mission. America desperately needed a victory, and Doolittle and his Raiders would deliver in stunning fashion, inflicting a blow upon Japan and shattering their belief in invincibility, which had been nurtured by no other successful invasion or attack of their homeland in the preceding 2,600 years.

The Raiders, along with supporting military personnel aboard the carrier USS Hornet, were part of an eight-ship task force that departed San Francisco Bay April 2, 1942. On April 13, well out into the Pacific Ocean, the task force merged with the eight-ship USS Enterprise Task Force, which had departed from Hawaii, to become the first joint full-scale operation between the Army Air Force and the U.S. Navy. Streaming toward Japan on a northern route to avoid detection, the 16-ship combined task force, consisting of 10,000 personnel, was discovered early April 18 by a Japanese patrol boat well ahead of the planned departure by the 80 Raiders in their 16 B-25 twin-engine bombers.

The discovery forced the Raiders to take off 12 hours earlier and 150 nautical miles further from Japan than planned. The weather conditions were miserable with rain, 20-knot gusting winds and huge waves crashing over the bow of the carrier. Yet, despite knowing they were likely embarking upon a suicide mission, the group of 80 volunteer fliers never wavered.

One after another, each B-25 lumbered down the deck of the carrier and took off. Following each other single file and flying by dead reckoning just above the wave tops to avoid detection, they reached Japan at midday and fanned out to drop four 500-pound bombs each on military and industrial targets in Tokyo, Yokohama, Kobe, Osaka and Nagoya.

Although some of the B-25s encountered light anti-aircraft fire and a few enemy fighters, none were shot down or severely damaged. Fifteen of the 16 planes then proceeded southwest along the southern coast of Japan and across the East China Sea toward eastern China, where recovery bases supposedly awaited them. The remaining B-25 ran extremely low on fuel and headed for Russia, which was closer.

The Raiders faced several unforeseen challenges during their flight to China: Night was approaching, the planes were low on fuel, and the weather was rapidly deteriorating. Realizing they would not be able to reach their intended destinations, their options were to bail out over eastern China or crash-land along the Chinese coast, areas occupied by the Japanese. When the dust settled, 15 planes had been destroyed in crashes. The crew that flew to Russia landed near Vladivostok, their B-25 confiscated, and the crew interned until escaping in May 1943.

Chinese locals and foreign missionaries who encountered the Raiders after they unexpectedly showed up assisted the Raiders and selflessly guided most of them to safety. The Chinese paid dearly for their help. An estimated 250,000 Chinese were subsequently slaughtered by the Japanese.

Compared to the devastating B-29 firebombing attacks against Japan later in the war, the Doolittle Raid did little material damage. Nevertheless, when news of the raid was released, American morale soared. The raid also had a strategic impact. The Japanese military recalled many units back to the home islands for defense, where they remained while battles raged throughout the Pacific.

The Doolittle Raid also provoked Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, architect of the raid on Pearl Harbor, to attempt a hastily organized strike against Midway Island, resulting in the loss of four carriers, a cruiser, 292 aircraft and 2,500 casualties from which the Imperial Japanese Navy never recovered.

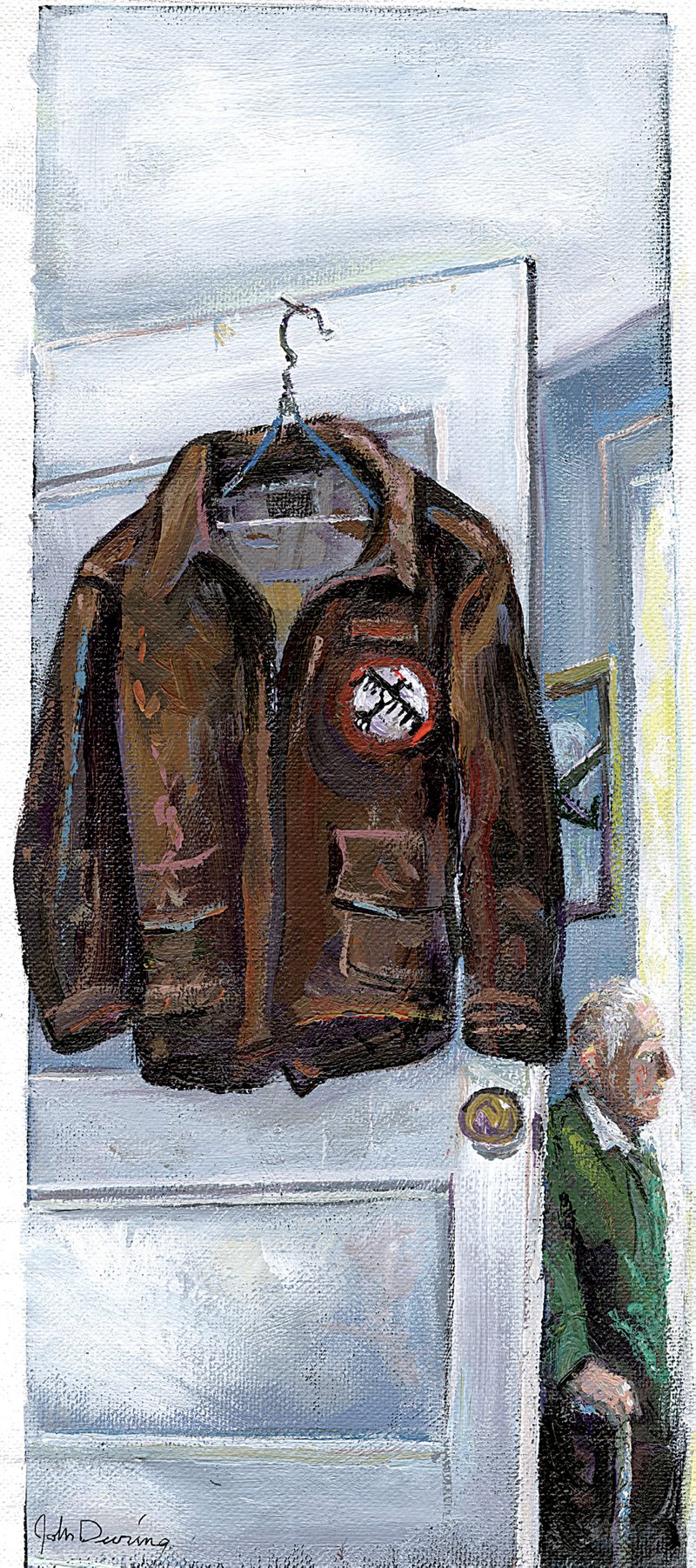

In December 1946 Doolittle and his Raiders gathered to celebrate his birthday, inaugurating what later became annual reunions around April 18 in locations throughout the U.S. During their annual reunion in 1959 the city of Tucson, Ariz., presented the Raiders with a set of sterling silver goblets, each bearing the name of one of the 80 men who flew on the mission. The goblets were housed in a special glass-enclosed case. Doolittle later turned them over to the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo., for safekeeping and display.

In 1973 Cole built a portable display case for the goblets so they could more easily be transported to the reunions. In 2005 the surviving Raiders voted to move the goblets from the Air Force Academy to the NMUSAF where they are permanently displayed alongside an exhibit featuring a restored B-25 bomber representing Doolittle's plane.

When transported to reunions, the 80 goblets were placed in a blue velvet-lined case consisting of four separate panels. Twenty goblets stand in each panel's compartment, placed five high and four across. Left to right they represent the crews--1 to 16--based upon their takeoff position in the Raid. Each column from top to bottom consists of the pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier and gunner. Each goblet has the Raider's name engraved twice so it can be read right side up or upside down.

At each reunion, two uniformed Air Force cadets accompanied the goblets, placed them in a private room atop a table, and stood guard over them. On the morning of April 18, the surviving Raiders would meet privately in front of the goblets to conduct their solemn ceremony. After calling the roll and toasting the Raiders who had died since their last reunion with cognac poured into the goblets by the white-gloved cadets, they would turn the deceased Raiders' goblets upside down.

In discussing his position last June as the last man standing among the 80 Doolittle Raiders after my father passed away, Cole said: "Mathematically, it shouldn't have worked out this way. I was quite a bit older, six years older, than David. Figuring the way gamblers figure, he would have been the last man."

Instead, Dick Cole is the last man standing. And when he raises his silver goblet for the final time to toast his 79 departed comrades on Tuesday, the longstanding tradition of the Raiders' private ceremony--which cemented the bond between the courageous volunteers, both enlisted men and officers, into a well-trained group who placed their collective duty as Americans above their individual lives--will end.

Jeff Thatcher is the son of the late Doolittle Raider David J. Thatcher and president of the Children of the Doolittle Raiders Inc., a non-profit group dedicated to keeping the legacy of the Doolittle Raiders alive.

Editorial on 04/16/2017