Only weeks before the expiration of one of the state's lethal-injection drugs, the Arkansas Supreme Court heard oral arguments Thursday on whether to uphold a trial judge's ruling that the state's execution law is unconstitutional.

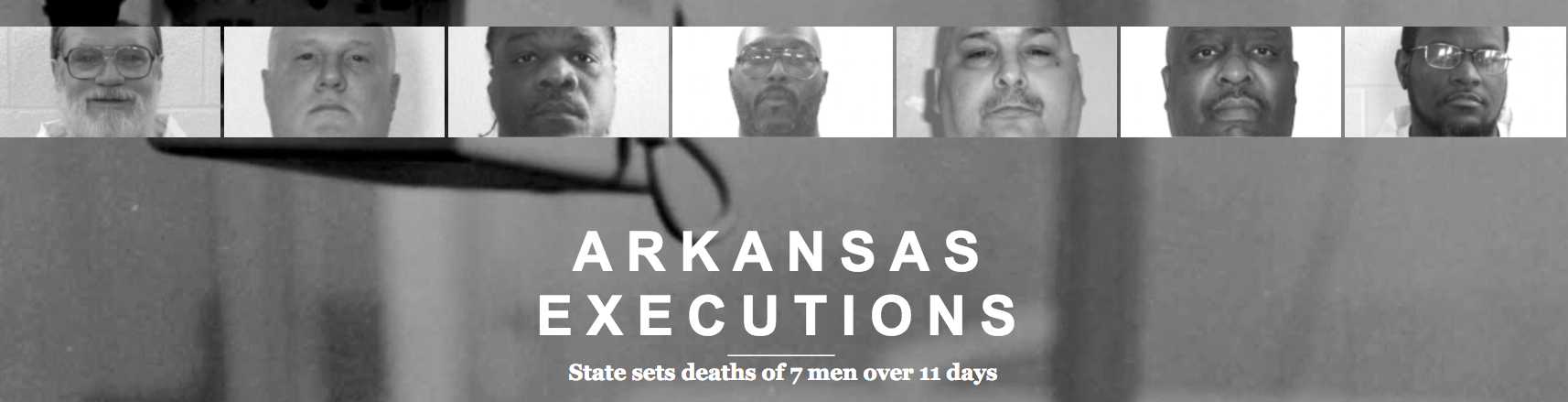

EXECUTIONS: In-depth look at 4 men put to death in April + 3 others whose executions were stayed

Click here for larger versions

Attorneys for the state argued that the high court should reverse the ruling, which invalidated the secrecy provisions of the law. The law prohibits public disclosure of the source of the drugs; prison officials and lawmakers say the secrecy is needed to protect a vendor from attention from execution opponents.

The attorney for the nine inmates challenging the law argued that the high court should uphold the December order by Pulaski County Circuit Judge Wendell Griffen, who voided the law because he said it conflicted with a constitutional guarantee of disclosure of publicly spent funds.

The inmates sued in circuit court shortly after the enactment of Act 1096, which changed the execution protocol to use of a three-drug cocktail -- including a sedative called midazolam that has been linked to botched executions elsewhere in the country -- and blocked public disclosure of the drugs' source.

Arkansas hasn't executed an inmate since 2005. Prison officials have enough drugs to conduct executions, but one drug is set to expire in June. Prison officials have said they are unable to buy more from the same vendor and have not found an alternative source.

On Thursday, the state's solicitor general, Lee Rudofsky, argued that the many claims filed by the nine death-row inmates were invalid and "not even viable" because the claims failed to pass requirements set by 2015 U.S. Supreme Court case Glossip v. Gross, which allowed the use of the same three-drug cocktail that is proscribed by Arkansas' law.

Rudofsky argued that Glossip required the prisoners to prove that the protocol would result in undue pain and suffering during the execution.

Rudofsky also said the 2015 ruling required the prisoners to demonstrate there were real and available alternatives the state could use for execution, and the inmates failed to demonstrate that.

"The first [alternative] they claim ... is an opioid overdose. No state in the history of the United States ... has ever used an opioid overdose. That is not a known alternative," Rudofsky argued. "They pleaded a firing squad. ... The only things they've pled are that there are a lot of people with guns in Arkansas and they know how to use guns ... Do you have to have an indoor facility so the wind isn't an issue? They don't prove that there's an available alternative that is actually available to [prison officials]."

An attorney for the inmates, John Williams, argued that the state constitution prohibits "cruel or unusual" punishment, a difference from the federal prohibition, which requires both, and that despite the Glossip ruling, there were questions of fact over the midazolam protocol that would need to be heard at the trial level.

He also argued that the state's execution law was void because Article 19, Section 12, of the Arkansas Constitution requires the state to provide an "accurate" and "detailed statement" of publicly spent money, including "to whom and on what account" the money was spent.

Rudofsky said that amendment could compel lawmakers only to decide when and what to disclose.

"There's actually nothing specifically in conflict between what the Legislature did and what the article requires," Rudofsky argued. "The Legislature doesn't say, 'Let's never release this stuff.' ... The article says, 'From time to time,' it doesn't say what 'time to time' is."

Chief Justice Howard Brill pressed Williams on the difference of opinion, pointing out that the Constitution empowers lawmakers to apply the constitutional imperative through legislation, like lawmakers did with Act 1096. Williams said that with Act 1096, lawmakers went too far.

Act 1096 "has not set the terms by which [the constitutional amendment] may be implemented. It has said [the drug records] shall not be published," Williams said. "That contradicts the mandate that it 'shall be published.' "

Justice Rhonda Wood told Williams that there are many laws regulating speech despite the free speech protections in the First Amendment. She asked what effect his reading of the state's public-records policy could have on things currently not disclosed -- for example, the identity of paid, unidentified police informants.

Williams said each case would vary.

"There are ways to narrow the amendment. ... In this case, there is no question there was an expenditure that was made [by the state]," Williams said. "The Legislature may set time, place and manner of regulations and that's what the [Freedom of Information Act] is. And it contains a number of exemptions. ... As far as what they may not do, they may not forbid a category of information to be published."

Metro on 05/20/2016