Pat Conroy died. The author had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in February and his demise came quickly, savagely. With that last breath, his vast vocabulary, storytelling wit, and gentle soul left us. But his books stay behind. Through those wonderful books Conroy's legacy remains in the boys of Catholic High.

Last July I was sitting on my porch enjoying a late summer evening with my middle son. He was reading The Great Santini and put the book down long enough to entertain a conversation with his dad. With the fan swirling lazily above our heads and the music of bugs in the background, he asked me what I knew about Pat Conroy. I took a sip of my drink and told him all that I knew.

Pat Conroy is Catholic High's favorite writer. Years ago, Fr. George Tribou began a handwritten correspondence with the rising author, and they formed a relationship of words borne by mail routes and enhanced by the stories they told one another. The correspondence included praise for Conroy's lyrical prose and criticism for the amount of profanity sprinkled within that beautiful prose. Though Conroy and Fr. Tribou never met face to face, they enjoyed a friendship of words.

I had the perfect combination of English teachers in high school. Mr. Steve Wells, still teaching at Catholic High, taught me my junior year and so lauded good writing that I found myself putting in extra hours to find new ways to please him, to receive his praise. Fr. Tribou taught me senior year. He was more methodical but insisted on strong vocabulary and weaving good stories. Both teachers came from the era before it became a mortal sin to have a boy put himself out there by reading his work aloud in class. They both insisted on us memorizing literature and reciting before the class works such as John Donne's "Meditation 17," the death scene from Cyrano de Bergerac, and bite-sized poems like:

"Two men peered from prison bars.

One saw mud,

One saw stars."

We were called on at random to stand and read our Monday essays. Early in the year, poor Ben stood in Fr. Tribou's class and started reading, "I got a new job yesterday. I really like my new job. My new job makes me work with people ..." Fr. Tribou skewered him. "That is the most mundane paragraph I've ever heard," he said. "I feel like I'm hearing someone recite numbers from the phone book. You must be more descriptive than that. If you must say things that everyone else is saying, you must say them in a different way, with different words, with different descriptors. Allow yourself to be poetic. Make yourself think of adjectives. No cliches, no worn-out euphemisms, no boring monosyllabic descriptions."

I looked around at the rest of the room and, collectively, we started erasing and re-writing our essays lest Fr. Tribou call on one of us to read the drivel we wrote late Sunday night. Current parents at Catholic High will tell you that when I send them emails, they are never short missives that get to the point quickly. I usually stitch a story through the pertinent facts and make what could be said in fewer than five sentences last two full pages. In fact, several parents have complained that I should be more brief, less descriptive, and just get the important information across. I just can't do that. I can't do it because somewhere in the back of my mind, I'm still that boy waiting for Mr. Wells or Fr. Tribou to call on me to read my work aloud.

And that was Pat Conroy. The man was the master of description and the greatest of storytellers. I read The Lords of Discipline as a high school kid and fell in love with words for the first time. I read The Great Santini on a trip to the beach after high school and acted out scenes to the embarrassment of my friends. I was handed a copy of The Water is Wide by Fr. Tribou right before I entered my first class to teach. Beach Music and The Prince of Tides swept through my early adult years. My Losing Season became a textbook for building character. As principal, I found South of Broad entertaining and The Death of Santini a road map for boys wanting to put their lives back together. I even bought Pat Conroy's cookbook and his mini-memoir, My Reading Life, in which he describes his favorite books. Conroy's books remain the anthem of my library, and I turn to their worn pages often.

In December 2000 Fr. Tribou became gravely ill, and his hold on life was weakening. I attended a Civil War artifacts conference in Charleston, S.C., that same month and struck up a conversation with a guy who was commenting on a glass case filled with artifacts from the Citadel. I mentioned that the guy must be a graduate and he remarked that he was a proud member of the class of '67. I perked up. That was the year Pat Conroy graduated from the Citadel, right?

"Did you know Pat Conroy?" "Know him? We were roommates for four years," was the response. I told the gentleman, Mike DeVito, about Fr. Tribou and his illness and asked that he let Conroy know. Mr. DeVito returned later and handed me his business card, with Conroy's private phone number on back. "You tell him," he said. "He'll want to hear it from someone who knows the father." I did not call. I simply couldn't be that starstruck fan who interrupted a great author.

Two months later Fr. Tribou died and I finally called the number on the back of that card. Hearing a mechanical answering machine voice, I left a message about Fr. Tribou's death that I knew wouldn't be returned. My wife and I gathered our coats and started to leave the house when the phone rang. We looked at each other and I walked slowly to the phone and answered. "Steve, this is Pat Conroy! I am so sorry to hear of Fr. Tribou's death ..."

Pat Conroy penned a handwritten eulogy of Fr. Tribou and faxed it to the school. In it, all of Conroy's characters in all of Conroy's books paid homage to the priest. A couple of lines stood out: I would have given a year of my life to have you as my English teacher. All the characters in all the cities I have created broke down and wept when I told them of your death. They thank you for teaching them so well. I thank you and love you for it. A copy of that eulogy hangs beside my desk.

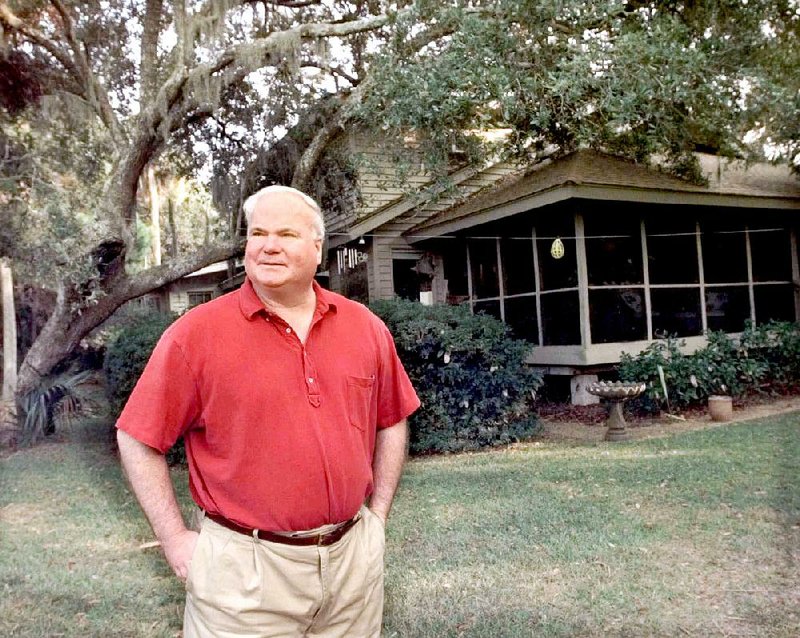

Conroy promised to visit the boys of Catholic High one day and pay homage to the priest who chastised him about his prolific profanity. After several months of jockeying schedules, we were about to give up on the author ever visiting. Then our librarian, Carrey Reynolds, and I stole a play from Fr. Tribou and cut up a yearbook. We cut out every photo of every boy pictured and stuffed all 700 images into a FedEx envelope with a note that read, "These are the boys you will disappoint if you don't visit Catholic High." A couple of months later Pat Conroy walked into our gymnasium to the standing ovation of teenage boys. He was welcomed as a hero, and, to us, that's exactly what he was.

Pat Conroy emailed me to check in on the school and the boys every once in a while. There was still a bit of that Catholic school boy within him and he couldn't help but revel in being the subject of an English teacher's lesson. I remember reading some critics who described his verbiage as over the top and the worst kind of purple prose. To me, it was storytelling poetry. It was a symphony without the music.

My son accepted my description of Pat Conroy with a nod of his head. Without another sound, he opened the book and began reading again. I watched the swirling ice that floated at the top of my drink and took a deep breath from the cool breeze blowing from the fan. I picked up my phone and wrote an email to Pat Conroy with the subject line: Fr. Tribou, Santini, Conroy, and a son.

Hello Mr. Conroy,

It's been a long time since we last visited at LR Catholic High, home of Fr. Tribou. This is just a quick note to let you know I am currently sitting on the front porch of my home built in 1928. The ceiling fan is blowing and the humidity is being kept at bay. My 14-year-old son, Sam, is sitting in a wicker chair next to me reading The Great Santini. He loves it. Just as I did when I was about his age.

Thank you for your words. Thank you for visiting Catholic High all those years ago. Thank you for loving Fr. Tribou from afar. He is alive today in your books and in the teenage boys who still enjoy them.

The teachers and boys of Catholic High prayed for Pat Conroy's soul the Monday after his death. And I, sitting at Fr. Tribou's old desk, whispered thanks that my English teacher and my favorite author would finally get to meet face-to-face.

Steve Straessle is the principal of Catholic High School for Boys and a proud member of the Class of 1988.

Editorial on 03/13/2016