Pharmacists feared a backlash from customers when the state enacted tighter regulations on pseudoephedrine five years ago, but the complaints never came.

"There was no outcry," said Arkansas Board of Pharmacy Executive Director John Kirtley. "That tells me a lot of it was being sold for illegal use, and the people who really needed it still got it."

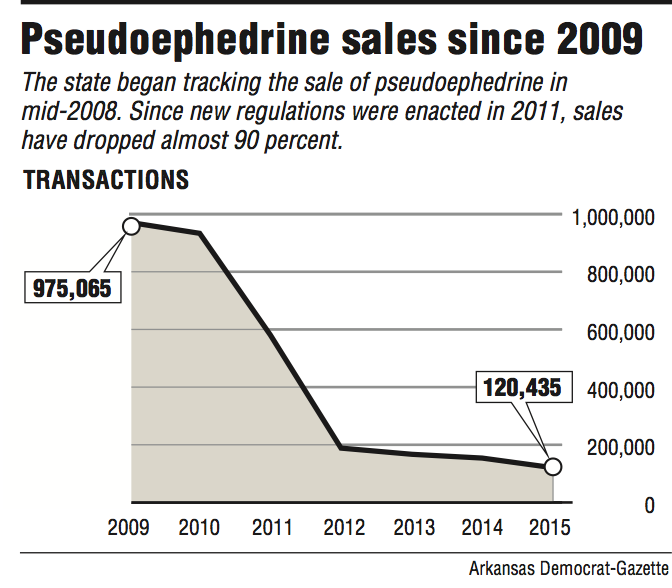

In 2010, there were 936,759 retail pseudoephedrine transactions in Arkansas, according to statistics from the Arkansas Crime Information Center. In 2012 -- one year after the tighter regulations -- retail sales of the drug dropped by 744,833 to 191,926, according to the statistics.

Sales continued to decrease after 2012. There were 120,435 pseudoephedrine transactions last year.

Pseudoephedrine is a cold and allergy decongestant medication. It's also a key ingredient used to produce methamphetamine, an addictive recreational drug.

Production of the illegal drug had surged in Arkansas, so the state Legislature restricted the sale of the key ingredient -- pseudoephedrine.

It was a balancing act between eliminating meth manufacturers' access to the drug, which was traditionally sold over the counter, without making it unavailable to people who legitimately needed it.

The law, Act 588 of 2011, required pharmacists to make "a professional determination" on whether a patient needed pseudoephedrine in the absence of a prescription.

That legislation followed Act 256 of 2005, which mandated that tablet forms of certain cold medications be sold from behind the pharmacy counter, and Act 508 of 2007, which created a law enforcement database to track pseudoephedrine bought at pharmacies.

Five years after the most recent law, methamphetamine labs have nearly disappeared, and pseudoephedrine sales have declined, but methamphetamine use and arrests for its use appear to be unaffected, said Matthew Barden, assistant special agent in charge of the federal Drug Enforcement Administration's Little Rock office.

South American and Mexican methamphetamine made in "super-labs" by drug cartels replaced the state's homemade version, he said. The new illegal drug costs less and is more pure.

Methamphetamine made with pseudoephedrine in Arkansas illegal labs usually is less than 25 percent pure, but the cartel-linked methamphetamine found in Arkansas has almost 100 percent in purity, Barden said. Additionally, cartels don't have to buy large amounts of pseudoephedrine from pharmacies, so their methamphetamine costs less, he said.

"Basically, this meth blows your high sky-high and gets you hooked," he said. "You can take it once, and you're a customer for life."

Even so, pseudoephedrine regulations were the right move for the Legislature to take, the DEA official said. Methamphetamine labs and the problems that accompany them have dissipated -- so much so, that the DEA, which used to receive reports on methamphetamine lab seizures from states, no longer tracks them, according to spokesman Debbie Webber. In contrast, a 2009 DEA report listed 486 lab seizures in Arkansas.

Craighead County Sheriff Marty Boyd said methamphetamine labs in northeast Arkansas were "rampant" during the mid-2000s. He remembers seeing four or five lab seizures every week during that period, when he was a deputy.

"We still see labs occasionally, but it's just not as frequent," he said. Like Barden, Boyd said the bulk of the methamphetamine his department finds now originates in Mexico. A few weeks ago, Craighead County deputies seized 2 pounds of "ice," or pure methamphetamine, from Mexico.

Fewer labs means fewer explosions and dump sites of the flammable and poisonous chemicals involved in making the drug, Barden said. Malfunctioning labs destroyed numerous hotel rooms, homes and rental properties over the years, and national forests became dumping grounds for defunct labs, he said.

Cleaning up the toxic chemicals from such labs can range from $2,500 to $20,000, DEA spokesman Rusty Payne said in 2011.

The reduction in the number of labs also cut down on the number of children admitted to Arkansas Children's Hospital for methamphetamine-related burns. The hospital treated 19 children for methamphetamine-related injuries in 2004. Hospital spokesman Hilary DeMillo said such cases are "rare" now.

"It's done its part," Barden said of Arkansas' laws.

The laws' impact has been more pronounced on the pharmaceutical industry, and pharmacists agree that the regulations accomplished the General Assembly's intent and more.

The 2011 law may have, unintentionally, helped many patients properly medicate, Kirtley said. Increased pharmacist involvement prevents consumers from purchasing the wrong medications for their symptoms.

"A patient may come up and say, 'My nose is runny. I need some Sudafed,'" Kirtley said, referring to the most common form of pseudoephedrine. "Well, if your nose is runny, you don't need Sudafed. You need an antihistamine like Benadryl."

Most methamphetamine "cooks" knew that the end of their business was near when the 2011 law was enacted, officials said. Brandon Cooper, a pharmacist at Soo's Drugstore and Compounding Center in Jonesboro, remembers turning a few people away after the law took effect, but "I think the people who wanted to use it illegally caught on," he said.

Now, Cooper rarely refuses to sell customers medications that contain pseudoephedrine. He sees most patients regularly and knows when they need the decongestant, he said.

For a new patient, it takes a few questions and brief review of medical history to determine a legitimate need, he said.

"If you need it, you can still get it without any problems," Cooper said.

Pseudoephedrine regulations came at a cost to pharmacies. Methamphetamine cooks no longer buy the decongestants in bulk, drastically reducing sales.

"Every piece of pseudoephedrine legislation, including the 2011 law, impacted pharmacists' ability to sell it and make money," said Scott Pace, executive vice president and chief executive officer of the Arkansas Pharmacists Association. "But that's something we're willing to do because it's what's best for the community."

Before the stricter laws, Pace said, some pharmacies were overburdened by "smurfers" -- cohorts of methamphetamine cooks who traveled in groups but entered stores individually to inconspicuously buy the maximum amounts of pseudoephedrine allowable per person under state law. The problem was noticeably out of control in southeast Arkansas, where Mississippi residents crossed the state line to buy "pseudo," a slang term for the drug, he said.

Some people, mainly lobbyists for consumer rights and pharmaceutical groups in Washington D.C., have floated the idea that states should loosen pseudoephedrine restrictions because methamphetamine labs have disappeared. Pace, however, said he hopes the laws remain unchanged.

"It's probably a lot like speed limits," he said. "If you repeal them, people are going to start speeding again, and traffic accidents will go up."

Metro on 02/15/2016