Gina Phillips might be called a painter: Her work begins with acrylics on canvas.

She might be called a quilter: She uses a long-arm quilting machine to attach fabric to that canvas.

FAQ

‘Gina Phillips: A Thirsty

Switch Still Quivers for Me’

WHEN — For the next five years

WHERE — 21c Museum Hotel in Bentonville

COST — Free

INFO — 21cmuseumhotels.com or ginaphillips.org

She might be called a sculptor: Her finished work is three-dimensional -- minimally, in a physical sense, but much more deeply in an aesthetic sense.

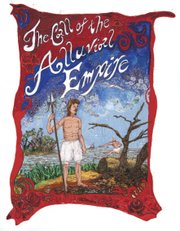

Phillips, who lives in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans, uses words like "hybrid" and "narrative" and "installation" to describe "A Thirsty Switch Still Quivers for Me," the exhibit currently on show at the 21c Museum Hotel in Bentonville. It brings together several bodies of work, she says, "but of course, I can see the thread between it all." No pun intended.

"Most of the work in the show is made out of fabric and thread," Phillips says, "but I almost always start out with an underpainting. I've always worked in two-dimensional and three-dimensional media, and this work kind of bridges those two worlds. It's rooted in painting but like really flat sculptures.

"People are always surprised when they get up close," she adds. "They think it might be a painting, but it's made out of all these appliques, materials, fabrics ... If it's possible to put it through a sewing machine, I probably have!"

It makes sense. Phillips' artistic roots are buried in rural Kentucky, where she grew up sharing a home with her grandparents and her single mother, who was one of seven children. "So I felt like No. 8 in the bunch," Phillips says. Her grandmother was a folk artist -- the title of the exhibit is based on lyrics of a song that Phillips wrote about her grandmother using a dowsing rod to find water -- and her grandfather was an auto mechanic who had his own junk yard on the property. Phillips and her cousins "built our own worlds" in the yard, she remembers.

"We were pretty poor, but it was a great environment to become an artist."

As she grew up, Phillips "put a little bit of pressure on myself, thinking I wanted to find a career that was lucrative." She settled, somehow, on becoming an architect -- but she didn't know she should have been taking art classes instead of drafting classes. Enrolling in one at the University of Kentucky, "I very quickly realized that was my true calling."

A decade after settling in New Orleans to seek an MFA at Tulane University's Newcomb College, Phillips bought a house and spent a year renovating it. And then Hurricane Katrina hit. She was out of town on vacation.

"It was a completely life-changing event for me," she says. "My neighborhood was kind of ground zero. I knew as of that morning, after watching the news footage, every house in my neighborhood was under water 10 feet high."

Phillips spent almost a year in Richmond, Va., before she could go home, another year and a half before she had recovered her house.

"One of the things that did come out of the storm was I started using a longarm quilting machine," she says. "I didn't know there was such a thing as a longarm quilting machine!"

It wasn't the only change that Katrina wrought.

"Some of the first work I made [after the hurricane] were these kind of weird pieces based on my flood-damaged photographs," she says. "This kind of crazy distortion happened on the surface when the chemicals were eaten away."

The "acid yellows and deep magentas and the weird, saturated, acidy colors stayed in my palette," Phillips muses. "Especially with the portrait series. My color choices became more bold and the surfaces more painterly. Now everything is becoming more painterly."

Also enhanced was Phillips' commitment to her city.

"One of the things that came out in my work was the sense of place," she says. "How unique this spot is -- how unique my neighborhood is, right next to the river. I realized how Eurocentric my understanding of history was, and I started to think about the Native Americans who would have been drawn to this spot on the earth. And the Mardi Gras Indians, who have this clear sense of continuity. And how the river will do what it wants to do: Nature will overcome human folly."

Even with that perspective, Phillips has bought in to the Lower Ninth Ward -- literally. She chose a house abandoned since Katrina to renovate as a studio.

"I think the imagery in ['A Thirsty Switch Still Quivers for Me'] really bridges my early life and the life I've had here in New Orleans for 20 years now," she says.

NAN What's Up on 11/13/2015