An overlooked and even forgotten chapter of American history played out in Arkansas during World War II. The American government established two Japanese relocation centers in southeast Arkansas.

Shelle Stormoe of the Arkansas Historic Preservation Program shared the story of the camps with students Monday at Lakeside Junior High School in Springdale. Lakeside media specialist Brian Johnson planned this and many programs throughout the year during the students' lunch times.

Web Watch

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

World War II Japanese American Internment Museum

To Read

Camp Nine

Author: Vivienne Schiffer

Publisher: University of Arkansas Press

Year: 2011

Questions of Loyalty

Japanese internees were asked the following questions as they entered relocation camps in southeast Arkansas. Some refused to denounce their allegiance to Japan because they were American citizens, not loyal to the country of their ancestors. Refusal to sign sent them to an more intense detainment camp in Tule Lake, Calif.

Question 27: Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

Question 28: Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese Emperor or any other foreign government power or organization?

SOURCE: World War II Japanese American Internment Museum

"It's the role of the library to bring the world to the students," he said. The topics of the war and the camps also fall under the eighth-grade U.S. history standards, he added.

Following the Japanese empire's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, "it felt very much like it felt after 9/11," Stormoe told the students, who were born in 2000 or 2001. "People were very angry and upset. It was a very emotional time. Thirty-six hundred soldiers had been killed or wounded."

President Franklin Roosevelt signed a declaration of war against Japan the next day. Anti-Japanese sentiment -- which had been building since the first Asian immigrants arrived in 1860s -- rose to hysterical levels throughout the United States, Stormoe said.

"(Threats against the Japanese residents) weren't based on anything other than racism," she noted. "After Pearl Harbor, everyone was convinced the Japanese were trying to spy on us. And California wasn't very far from Japan -- within a day ... for an airplane or ship. The government was worried they would attack the homeland."

Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, making the West Coast a military zone, giving military officials authority to exclude anyone from this part of the United States. "But only the Japanese were excluded," Stormoe said.

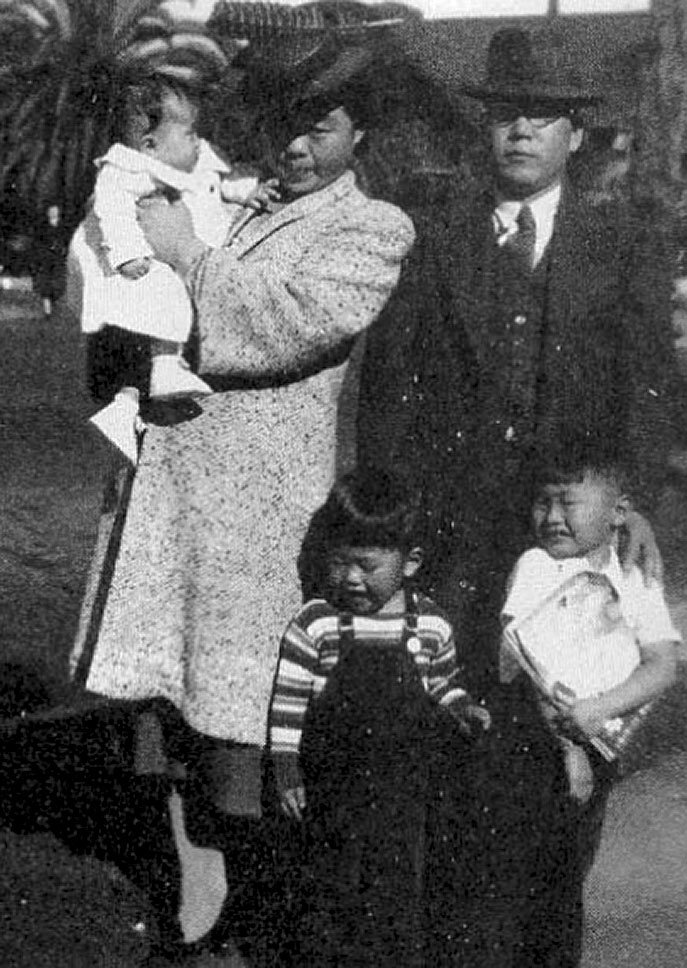

Many of the Japanese living along the West Coast were Nisei -- second- or third-generation Japanese born in the United States -- and were citizens. Among the 110,000 Japanese who surrendered to the government, 70 percent were American citizens and 40 percent were children, according to information from the World War II Japanese American Internment Museum in McGhee. Throughout the war, 16,000 Japanese were transported by train to Arkansas.

"Their grandfathers or great-grandfathers were among those early settlers," Stormoe said. "Most Nisei spoke English; they didn't even know the Japanese language. They were American citizens and worked as doctors, lawyers, teachers, shopkeepers and farmers."

First, Japanese -- U.S. citizens or not -- were required to take their radios and other electronics to local police stations for inspection that they were not equipment used in spying.

"In fact, there was very little evidence of spying," Stormoe said.

Then, postings showed up in Japanese neighborhoods, telling all persons of Japanese ancestry they had two weeks to gather two bags of their belongings and report to the train station.

"They had no idea where they were going or how long they would be gone," Stormoe said. "They didn't think it would last long. They thought, 'I haven't done anything wrong.' But they were terrified. They were loaded onto the trains at gunpoint."

In the Arkansas Delta

The two camps in Arkansas -- at the small towns of Rohwer and Jerome, about 30 miles apart in Desha County near McGhee -- were the farthest east of all camps, located on land owned by the federal government. Stormoe said all camps were in isolated areas but on railroad lines to easily transport the Japanese.

"Now, if you were Japanese, and escaped from the camp, wouldn't you stand out in towns along the Arkansas Delta?" she asked the students. Students agreed.

Rohwer and Jerome became some of the largest towns in Arkansas almost overnight.

Barracks were hastily built to house the Japanese. Each of the 60 barracks at the Rohwer camp encompassed about 2,400 square feet -- "about the size of an average American home," Stormoe told the students. "But six families had to live in that space. Each family got about 400 square feet. That's about the size of your living room."

Community laundry, shower and latrine buildings and a mess hall served several barracks.

"There were no private bathrooms," Stormoe pointed out. "Everything was public. They were humiliated."

Students attended school in the camps, taught by white teachers from the surrounding community. And many adults took classes related to hobbies or had jobs in the camps as graphic artists, storehouse labor, secretaries for the administration or farmers. The camp also included a garage, a sawmill, a post office and electrical and plumbing shops.

These jobs provided the residents with their own money, but they were paid half or less than they were paid in their outside jobs, Stormoe said.

Interestingly, Japanese farmers were able to tame the overgrown swamps by draining and clearing the land using traditional Japanese methods -- something the white farmers hadn't been able to do. Fruit -- especially watermelons -- were successful crops, as was a hog-growing operation.

The relocation camps became self-sufficient, growing their own food. In fact, residents of the Arkansas Delta resented those in the camps, who had better food, homes, schools, medical care and pay than many of those outside. "Those living poor in the Delta thought the Japanese were getting special treatment," Stormoe related.

Many of the conditions sound similar to those of the concentration camps operated by the Nazis during the war, Stormoe said. "The conditions were better, and the people obviously were treated better," she said. "But they couldn't leave. They had no privacy. They had to abandon all their things and show up with only what they could carry. They had to raise their children behind a razor-wire fence." Their mail was translated and censored, categorized as "detached alien enemy mail."

"To escape meant death," she added. "There were guard towers, and they had guns pointed at them at all times.

"Lookswise, the two places seemed similar. But don't confuse the internment camps with concentration camps," Stormoe insisted. "As terrible, horrible a thing as this was, it was not as bad as what happened in Germany. Those were death camps. People were held until they were killed."

Pledge of Allegiance

Another part of the process for the Japanese was signing an oath as they entered the camps. Questions No. 27 and No. 28 proved problematic. The internees were asked if they would fight for the United States in the war and to renounce their allegiance to the Japanese emperor.

Many Japanese refused to sign the oath because, by renouncing their allegiance, they were admitting to an allegiance to Japan -- which simply wasn't true. "They were so angry, they refused to fight for the U.S.," Stormoe said.

Those who refused to sign were labeled as traitors and taken to a more intense camp in Tule Lake, Calif.

The family of George Takei -- the actor who played Mr. Sulu in the original "Star Trek" series -- was one of these. When he was 4 years old, the family was forced from California.

However, 300 of the young Nisei interned in Arkansas did agree to fight for the U.S. The 442nd regiment combat team was mustered at Camp Shelby near Memphis, Tenn., according to the internment museum. Ten thousand men fought some hard battles in this Japanese unit.

"This was the only country we knew. This was home," a soldier says in a video presentation at the museum.

The Japanese surrendered after the United States dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When the war ended, the Japanese detainees were allowed to return home, but they found their homes and businesses destroyed. "Anything they owned had been looted and vandalized," Stormoe said. "They had no money, no jobs, and there were many other injustices.

"People who knew about in the removal in advance tried to sell their property," she said. "The Takei farm sold for $5. But the Japanese were not required to turn over any property or belongings to the government."

Stormoe pointed out that Takei's father put his books in storage before he left for the camp, and he paid his bill every month throughout the war. But when he got back to California, all Takei's books were gone and no one had any idea where they were.

In 1988, Congress awarded restitution payments of $20,000 to each survivor of the camps. "But this was in no way enough to make up for what they lost in their lives," Stormoe said.

Gone and forgotten

Today, little evidence remains of the southeast Arkansas camps. Jerome has been completely wiped out by time and a bean field, and Rohwer is little more than a cotton field, Stormoe said, but a few structures remain.

A cemetery established by the Japanese -- holding 24 graves of both old and young -- survives as the only site identified as being part of the internment center. The inmates created the headstones and memorial markers seen today.

Unrest in the Jerome camp, where the residents were much more challenging to authority, might have aided in its disappearance, Stormoe speculated. That Japanese community did not band together for projects such as the cemetery.

After the war, the Army sold the buildings of the camps as surplus, and many Delta residents incorporated part of the barracks into their own homes, perhaps as additions.

"But, mostly, the camps were wiped out like they did not exist," Stormoe said. "Many people ignored the fact they were there."

The private land owner has provided an easement for access to the site of the former Rohwer camp, which is cared for by the heritage studies department of Arkansas State University, Stormoe said. A reproduction guard shack stands at the entrance to the field with an audio presentation about the history of the camp, and the smokestack of the hospital incinerator stands in the distance, a testimony to the enormity of the camp.

The Rohwer site is listed as a National Historic Landmark, which is more important than simply being listed on the National Register for Historic Places, Stormoe told the students. "It's important because it's national history not just local history."

Takei, other now-adult children from the camp and their descendents spearheaded the efforts to preserve the camp and give a different perspective, she said.

"It's messed up," said Lakeside student Johnny Miranda said of the historical events surrounding the camps. His friend Sebastian Ortega admitted he was afraid such a situation would happen again -- to people of his ancestry.

"Hopefully, we learned some things during World War II," Stormoe said.

"It's not as messed up as the concentration camps," concluded student Caleb Arrington. "But it's still messed up. Why couldn't they go home if they wanted to? They should have let them leave."

Laurinda Joenks can be reached by email at [email protected].

NAN Profiles on 03/22/2015