Amid Victorian-era houses sporting touches of Spanish Revival and mansard roofs, beside a slate sidewalk and across the street from a new playhouse -- and across another from a motor lodge cum apartments -- is Eddie Walker Jr.'s office.

The Walker, Shock and Harp law firm, a low-slung ranch-style assemblage, won't earn a listing on any historic register -- and maybe that's a good thing. In 1996, a powerful tornado destroyed as many as 80 commercial properties in the area, ripping the roofs off several 19th-century brick and stone structures downtown. As one resident told a reporter, the "lightning was green. The sky was pink. The wind was blowing and the lights went out."

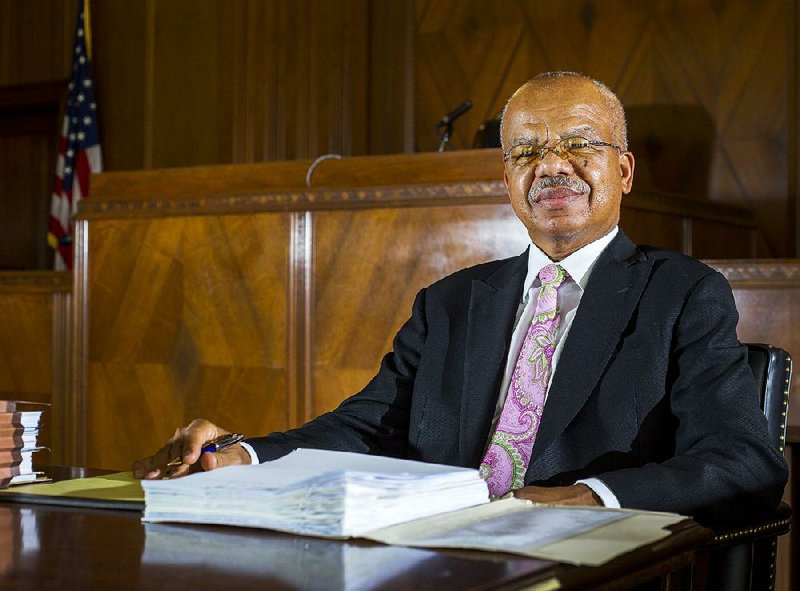

Eddie Haywood Walker Jr.

Date and place of birth: Sept. 13, 1950, Wabbaseka

Family: wife, Gwen; son, Jammie, 25; daughters, Johannah, 22, and Janelle, 20

My fitness routine is to push myself away from the table at the appropriate time.

The tricky part of fatherhood as a lawyer is sometimes, because of the analytical approach most lawyers take, it can cause you not to be as compassionate [as you could]. What I sometimes say — it’s not always enough just to be right. You can be technically right but the situation is such that you need to make an emotional accommodation, if you will.

The law school professor I’d like to have a drink with today: Al Witte, whom I had for contracts as a first year. … He’s just a colorful guy. He’s a good professor, but he has got a colorful personality.

I’m reading Outthink the Competition: How a New Generation of Strategists Sees Options Others Ignore, by Kaihan Krippendorff

People say I sound like Lou Rawls.

A smell that makes me nostalgic: That summer rain; reminds me of growing up on the farm.

My last meal? I’m a steak man, so filet mignon and whatever sides the chef thought were appropriate complements.

If I were marooned on a desert island, I’d be busy trying to figure out a way to get off that island.

Three people at my fantasy dinner party: Jesus, Job, and Warren Buffett or Bill Gates

If I’ve learned one thing in life, it is your future is often filled with unimaginable opportunities.

My favorite vacation spot is Hawaii

A word to sum me up: Reasonable

The damage the Shock and Harp firm sustained precipitated the addition of a couple of upstairs offices and a new named partner. For nearly 20 years now, it has been Walker, Shock and Harp PLLC.

The senior lawyer's practice is largely workers' compensation cases, and he's a claimant's attorney (in this area of the law, it's claimants and respondents). Across the aisle from him are often defense attorneys representing insurance companies -- men like Scott Zuerker, an understudy of Walker's before he went corporate.

"Eddie is certainly one of the most knowledgeable and well-read claimant's attorneys that I encounter," Zuerker says, and so, fairly intractable in the face of any shifty lawyering. And "Eddie is, above all else, a very reasonable person. You've no doubt heard the legal standard 'the reasonably prudent person?' ... Several of us joke that if you were to look up 'reasonably prudent person' in Black's Law Dictionary, you'd find Eddie's picture."

"Eddie had a chance to become a federal judge once, and I think every insurance company called and put in a good word for him -- to get him out of the business," says his partner, David Harp. "You go around and ask any of the judges, any of the top defense attorneys in Little Rock who do workers' compensation, they'll tell you -- Eddie Walker's probably the best."

All right, that may or may not hold up under cross-examination, but here's a statement that's indisputable. On Friday, Walker will be sworn in as the 118th, and first black, president of the Arkansas Bar Association. He'll be administered the oath by Justice Paul Danielson of the Arkansas Supreme Court before a lunch crowd of roughly 600 lawyers and supporters inside the Hot Springs Convention Center.

The first order of business: the successful transfer of leadership responsibilities. Then, new priorities! Well, a fresh crack at well-visited priorities, anyway.

"As bar president, you realize things that you started your year are not going to get finished," says current president Brian Ratcliff, of the PPGMR law firm in El Dorado, "and you're going to finish other people's projects ... and take credit for it!"

So, this kind of presidency is about continuity. Right. But it's also about progress, and for that, "it couldn't be a better person."

This is the culmination of a kind of dream in Walker's head that stretches to 1979, to his first bar association meeting in Hot Springs, where he "saw people walking around with a lot of ribbons" -- identifying them as judges and association officers -- "and I wanted to someday wear some of those ribbons."

He was born near Pine Bluff in the tiny town of Wabbaseka but lived in the tinier town of Gethsemane. Asked about growing up in a place named for the garden of Jesus' anguish, he says, "That's probably why I'm such a nice guy."

One of Walker's earliest childhood memories is falling outside and gouging his hand on a broken soda bottle. The thick shard severed some tendons and ligaments. It precipitated more than one surgery, and the early prognosis was that he would lose quite a bit of motor function. That he rehabilitated it completely is a credit to "the persistence of my mother."

In fact, Jammie Walker was persistent about a great many things. Walker was raised by his mother (and, in loco parentis, his two older sisters). Consider the allure of sports for a young boy. Despite his 6-foot, 2-inch frame, Eddie Walker has not been hampered by the athletic distractions of youth. "I was more of an egghead." Oh, he wouldn't have minded being more athletic, he supposes, but "I figured being smart was a surer ticket" out of the garden "than being an athlete."

Anyway, "that was the general sentiment of my mother, and I pretty much did what she told me to do."

Despite being a self-described "exceptional student," the one instruction he wishes he'd taken more seriously is typing. "When I was in high school they offered typing. I thought, 'Why would I need to type?'" If all went according to plan, after all, his secretary would do his typing. "Consequently, now, I hunt and peck."

WHITE AND BLACK

Gethsemane then was a farming place with modest lives and prospects. Kids began picking and chopping cotton in primary school.

Being on a farm meant cultivating 10 acres, maybe 20, and by hand. Slowly the men, and then the women, began commuting to Pine Bluff for commercial and industrial work; some went farther still, into Little Rock.

All three Walker kids went to college. For the baby, the land-grant Arkansas AM&N (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff) would have stood out as the most predictable choice, geographically and demographically: the school in Pine Bluff is one of the nation's historically black colleges and universities, and in as familiar a place as any. Walker instead chose the other land-grant school, the big one, in Fayetteville.

When he got to campus he found there were no black scholarship athletes -- the next year Jon Richardson and Jerry Jennings broke the color barrier and integrated the football program -- and some days he didn't see another black person on campus until he returned to Hotz Hall.

About the time that Walker was set to walk over to the law school, in 1971, a story in the Arkansas Gazette pointed to a Department of Health, Education and Welfare report that estimated the number of black undergraduates at 1.7 percent of a student body pushing 10,000. (At about 5 percent, it continues to underrepresent the state's black population, which the U.S. Census in 2014 estimated as 15.6 percent.)

But the splendor of the spectrum of students in Fayetteville delighted him. His satisfaction and happiness must have been contagious, because as a sophomore he beat out a white candidate to win election to the Student Senate.

"When I went to college, I felt like there were things I'd not been exposed to, having come from a small, country, segregated high school. ... There were no white students [in high school]. There were only 23 in my entire graduating class."

Not long after Walker won a seat on the student Senate, another black student came along and broke the ultimate barrier. Gene McKissic of Pine Bluff was elected president of the student government in 1972. Both men then attended the law school, where they knew each other only casually.

This is how McKissic reflects on his achievement today: "It's something that's important as far as a statement: The UA was ahead of its time and exemplified leadership for the state. On the other hand, reality forces you to acknowledge that you were not the first black person who was capable of serving as student body president -- you were just the first person who had a realistic opportunity."

Today, "I do think in many ways we have grown past excluding people on the basis of race and gender." In the case of the bar association, as with other meritocratic orders, "you have to pay your dues."

"A black lawyer could have served as [bar] president prior to now. The question is, 'Do you get in, do you work, do you serve, and do you handle your business ... in such a way that you have the respect of your colleagues?'"

Walker did, and Friday, McKissic will be there to shake his hand, but "on being president of the bar, not necessarily on being the first black president."

Will he make a good one? President, that is.

"I think Eddie Walker will make an excellent president," says Ratcliff. "He's well-spoken, and one thing about Eddie, he will listen before he talks -- and that's not always easy to do."

"He has a great sense of humor," says his partner Harp, "and when you hear that laugh, you know it's Eddie."

Nearly everyone who speaks of Walker mentions his laugh. It leaves his body like a harlequin handkerchief from a wool suit pocket.

LIKABILITY

Although he has tried cases before the state Supreme Court and even served as a special associate justice of the court, there's no one case that has defined his career. "I've never thought of one as being a case I would put a plaque on the wall about."

He abjures the common fiction that lawyers are cutthroats or pugilists. In fact, he loses his strong sense of decorum in the face of such stereotypes.

"A lot of times, disputes can be resolved in such a way you don't have to crush another side. We're not Roman gladiators out to kill each other. ... You can be a zealous advocate without being a jackass."

And that's a function of the bar association. Civility, and ethics. Walker has served on the state Supreme Court's Committee on Professional Conduct, even chaired it, and he has served on the bar association's committee of the same name. (Today he's chairman of the association's Law School Committee.)

Zuerker, the courtroom "adversary," is also an adjunct professor at the law school in Fayetteville, where he has in the past conducted a bar association seminar called "Bridging the Gap." His lecture uses as its study a workers' compensation case he and Walker argued, and he invites Walker in for the lecture. The case was decided at the trial level, reversed by the Workers' Compensation Commission, and moved to the state Court of Appeals before it ultimately settled out of court. It illuminates a real-world principle of lawyering that feels counterintuitive: Opposing counsel, at the height of their powers, will muster the full breadth of the law's direction on a particular subject. They'll dispense with stagecraft. They'll nearly work in tandem.

"One thing that surprises people -- for example, when I'm writing a brief, I'm essentially arguing why I should win. Now, in the process, if there's a case out there that I know of that is bad for my client, or the law is in conflict with what I'm asking the court to do, I'm ethically obligated to point that out to the judge. That's the framework we work in," and within that framework, Eddie Walker "is one of the most ethical lawyers I've been around; one of the most ethical people I've ever been around," Zuerker says.

Ethical, but likable, to be sure. Several voting members say what wins the day with them is servant leadership, and likability.

"When I was a student senator ... I think that the fact that I was taught the importance of treating people courteously, kind, treating folks with dignity, the value of 'Please,' 'Thank you,' 'Excuse me.' I think all of those things contributed to my ability to function in a setting where many would be uncomfortable. And it ended up making me a likable guy!

"That may be egotistical, but the truth is I consider myself a likable guy."

NAN Profiles on 06/07/2015