WASHINGTON -- Most Saturday mornings, former U.S. Sen. Bob Dole, R-Kan., greets fellow veterans at the southern entrance of the National World War II Memorial, shaking hands and posing for photos with a steady stream of visitors.

On July 18, between asking the veterans where they're from, where they served and how old they are, the former presidential candidate ("I'm 93," boasted Bill Hovestadt. "I'm going to be 92 on Wednesday," Dole replied), was lobbying for support for the beleaguered National Eisenhower Memorial.

When tour buses carrying veterans from San Antonio and Austin pulled to the curb, volunteers helped the elderly men and women into wheelchairs and pushed them along. As the veterans passed, young uniformed soldiers, tourists pushing strollers and volunteers stood in the rain to cheer and applaud. Many called out, "Thank you for your service."

At the center was Dole, who worked the crowd like a candidate on a campaign trail. He led the effort to raise more than $170 million for the privately funded World War II memorial that opened in 2004. Now his mission is to get a memorial built for Dwight D. Eisenhower. Dole served under Eisenhower in Italy, and he considers Eisenhower, a fellow Kansan, "one of the great Americans." It's a view shared, he believes, by many World War II veterans.

"It's been 16 years. We've got to get it built," he told Harold Shockley, 90, about the stalled memorial to the World War II general and 34th president.

"He was our hero," he said to Delbert Armstrong, 88. He repeated the statement to Norm Riggsby, 90; Smokey Brittingham, 89; and John Gumfory, 88.

The Texas veterans represent a handful of the 855,000 men and women still living of the 16 million who served, Dole said. Almost 180,000 World War II veterans die each year.

"I want to get it built before all of us are gone," Dole told Tino Rodriguez, 95, who signed Dole's petition seeking support for the $142 million project.

It will take all of Dole's political skill to succeed. Authorized by Congress in 1999, the Eisenhower Memorial slogged through the federal regulatory process. Earlier this month, architect Frank Gehry's modified design received final approval from the National Capital Planning Commission, weeks after another federal agency, the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, gave its final approval.

But Eisenhower's family, led by granddaughter Susan Eisenhower, has not embraced the design. As a result, two congressional appropriation committees declined to provide any of the $68 million the Eisenhower Memorial Commission sought for 2016. By law, construction can't begin until full funding is in hand.

"It simply defies logic and decency to design and build a memorial to Dwight Eisenhower without obtaining the approval of the Eisenhower family," U.S. Rep. Ken Calvert, R-Calif., chairman of the appropriations subcommittee with jurisdiction over the project, said in June.

Critics such as the National Civic Art Society and Right by Ike group have accused the commission of having a stubborn desire to create a modern memorial. Supporters say the opposition, while vocal, is only a small group fueled by a desire to defeat Gehry.

Dole isn't interested in blame.

"I don't want to fault anybody. I just want to get it built," he said from his office at the law firm of Alston & Bird, where he is special counsel. "I respect the family, but I also respect the veterans who served under Ike. We ought to have some say in it."

The road to building a memorial in the nation's capital is often long and messy, and the Eisenhower project is no exception. It took 42 years and several design competitions to complete the memorial for Franklin D. Roosevelt, while the World War II memorial needed 11 years to finish.

The Eisenhower commission spent the first six years securing the 4-acre site along Independence Avenue, a block from the National Mall, and three more to select Gehry through the General Services Administration's Design Excellence Program, a choice that continues to plague the commission. Unlike other competitions, such as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the Eisenhower contest sought designers, not specific designs.

The past five years have been consumed by debate over Gehry's vision. Originally, it featured three stainless steel tapestries, bas-relief sculptures and a statue of a young Eisenhower gazing into his future. Although David Eisenhower served on the commission board when the initial design was adopted, he and his sisters later criticized it as too romantic and complained that it did not do justice to their grandfather's global achievements.

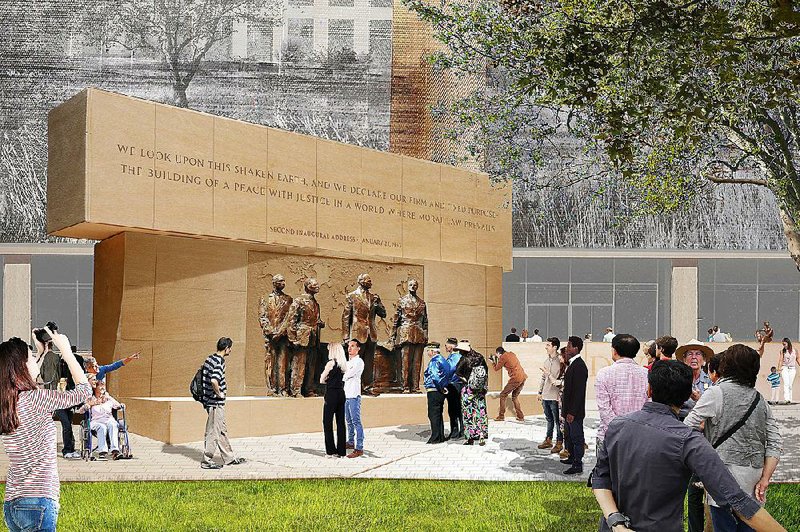

Commission officials said they have listened to the family's concerns. Gehry's original plan has been modified to remove two stainless steel tapestries that helped to frame the park's perimeter. There's still a statue of a youthful Eisenhower, but the memorial core now features one bronze sculpture depicting Eisenhower as the supreme allied commander during the war and another bronze statue showing him as the president.

The family has not made any public statements about the most recent design, although in a letter to the commission in September, they said they favored a "simpler design" or a new design competition.

In an email, Susan Eisenhower said she sympathizes with Dole and other veterans who want to see that the memorial is built.

"My family and countless other people are working very hard to make this happen, and to assure that the memorial reflects the consequential nature of Eisenhower's service to this country -- in war and peace," she said. "It will be the nation's gift to future Americans, just as other presidential memorials have offered inspiration to rising generations."

Although the Eisenhowers and others have lost the design battle, the skirmish continues over funding. The groups that railed against Gehry's design are changing their arguments to focus on the flawed selection process and the commission's inefficient operations. The end game remains the same: prevent the current design from being built.

It seems to be working. The House and Senate appropriations bills provide no construction funds, notes Justin Shubow, president of the National Civic Art Society and a relentless critic.

"The House [budget] language call for a reset and to fire the staff," Shubow said.

The National Civic Art Society has about 100 members and had an operating budget of $59,000 in 2014. Shubow says the organization hosts lectures about civic architecture. The tax filings, however, show that 94 percent of last year's program funding was used to "educate the public and decision-makers on issues related to the process and design" of the memorial.

The largest donation to the National Civic Art Society in 2014 was $33,000 from Richard Driehaus, a Chicago philanthropist who promotes classical art and architecture. Shubow said Driehaus hasn't donated any money to the National Civic Art Society this year, but Driehaus is a member and funder of Right by Ike, the group that pays its spokesman Sam Roche and D.C. lobbying firm ASGK Public Strategies to block the memorial.

Driehaus did not return a message left at his Chicago foundation, but in March, he told an architectural magazine that he is funding the opposition because "architecturally, it doesn't speak to me. We want something more representational."

The memorial commission has ramped up its fundraising. It recently announced that journalist and The Greatest Generation author Tom Brokaw has joined its advisory council, soon after cheering its largest gift to date, a $1 million donation from the government of Taiwan. Total donations are at $1.5 million, officials said. The commission has received $46 million in federal funding. It hasn't disclosed the final cost of the revised design.

But officials have changed their tactics, asking lawmakers for $24 million in the 2016 budget and permission to complete the project in stages. Dole is making calls on their behalf, but he is losing patience. The memorial will take three years to build, he said, and thousands of veterans will die each year.

"If we can't satisfy the family and other naysayers, we should forget about Congress and raise the money privately," he said. "If they get it started this year, I'm planning to be at the dedication, God willing. But I want some other guys with me."

SundayMonday on 07/26/2015