ORLANDO, Fla. -- Accusations of spying have put a new twist on the battle between SeaWorld Entertainment and animal-welfare activists, which experts say could cause more trouble for the theme-park company.

Orlando-based SeaWorld has opened an investigation and placed an employee on paid leave after People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals accused the employee of attending protests posing as an activist.

The employee's actions have not been confirmed, and it's not known whether SeaWorld management had any involvement in what PETA contends was a mission to spy and encourage other animal advocates to misbehave.

SeaWorld declined to comment beyond two statements it has already issued, including one from new Chief Executive Officer Joel Manby that called the accusations "very concerning" and said an outside law firm will investigate. "These allegations, if true, are not consistent with the values of the SeaWorld organization and will not be tolerated," he said.

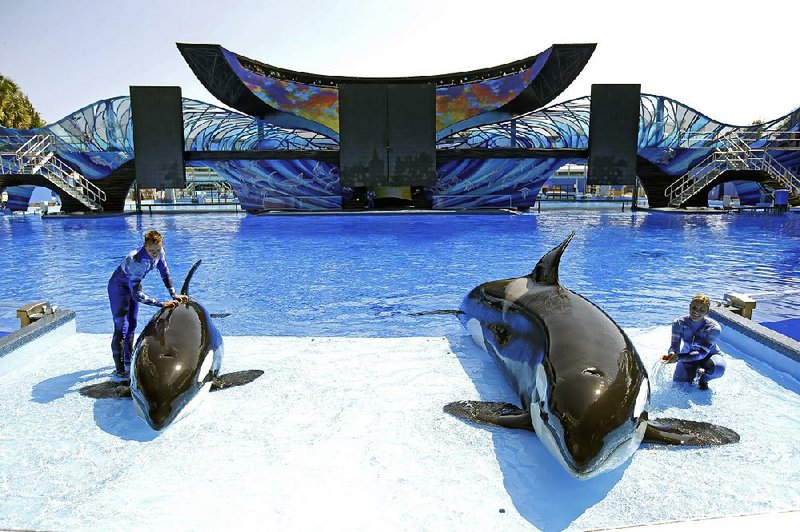

The accusations are particularly troublesome for Orlando-based SeaWorld because of the questions it has faced over keeping whales in captivity, some say.

"From a public-relations standpoint, it's a mess," said Mark Johnston, a professor of marketing and ethics at Rollins College's Crummer Graduate School of Business. "What they've managed to do here is make PETA a bit of a victim."

PETA's accusations were first reported by Bloomberg News last month.

SeaWorld did not name the worker involved. PETA has identified him as Paul McComb, a human resources employee at SeaWorld's San Diego location, and says he used the alias of Thomas Jones. A Thomas Jones on Twitter has made inflammatory social-media posts. One invited people to help him drain SeaWorld's new orca tanks. Another suggested a protester might burn SeaWorld "to the ground."

McComb could not be reached for comment. PETA says it has identified three more people who have protested SeaWorld but could actually be affiliated with the company.

It's not unheard of for both corporations and nonprofits to gather intelligence on critics or competitors, said Kirk O. Hanson, executive director of Santa Clara University's Markkula Center for Applied Ethics.

"To me, the line is crossed when one presents oneself deceptively and certainly is crossed when one tries to incite violent action," Hanson said.

Typically companies that snoop on critics hire outside firms to put some distance between them and the surveillance, said Gary Ruskin, who authored a 2013 report on corporate espionage for a nonprofit citizen-activism organization, Essential Information.

If management encouraged its own employee to spy, Ruskin said, "it's espionage incompetence on the part of SeaWorld."

Corporate sleuthing of adversaries and competitors goes back decades. In the 1960s, General Motors hired a detective to dig up dirt on consumer advocate Ralph Nader.

In 2008 Burger King was caught hiring an unlicensed private investigator who tried to work with student activists who wanted to subsidize higher wages to tomato pickers. About the same time, online posts criticizing the farmworker activists were traced back to a Burger King vice president who posted under his daughter's screen name. He and another executive were fired and two months later, Burger King gave in to the activists' demands.

Undercover work is also conducted by activists, including an anti-abortion group that recently released surreptitiously recorded video of Planned Parenthood employees discussing how they provide aborted fetal organs for research.

SeaWorld pointed out that PETA conducts espionage of its own. It cited a job post seeking an undercover investigator whose duties could include obtaining work in "industries that use animals."

PETA says its investigators generally respond to whistleblower complaints and seek to uncover illegal activity. They don't use fake names, senior vice president Kathy Guillermo said. "It's a night-and-day difference," she said.

PETA said the man known as Thomas Jones first joined its activist network in 2012. He raised the group's suspicions after the arrests of more than 15 protesters at the Rose Parade in Pasadena, Calif., last year. Jones was among those arrested but, unlike others, was released without charges. PETA traced the tag of Jones' car back to McComb, according to Bloomberg. The group also discovered that one of two addresses he'd provided when signing up for its "action team" didn't exist. The second was registered to a SeaWorld security director in San Diego, PETA said.

PETA has filed suit against the city of Pasadena seeking public records from the Rose Parade arrests.

For Manby, the controversy will be a big challenge, said Scott Smith, an assistant hospitality professor at the University of South Carolina.

"Joel Manby has to realize this is one of his first tests of character ... how he's going to be perceived and can he be trusted," Smith said.

SundayMonday Business on 08/09/2015