By many accounts, county jails across Arkansas have become more violent and tense as the number of state convicts and parole violators awaiting transfers to prisons flow in, crowding out many of the misdemeanor offenders and pretrial detainees that the jails were designed to hold.

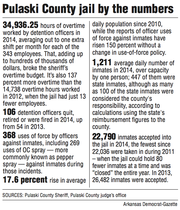

At the Pulaski County jail -- the state's largest county lockup -- physical confrontations between officers and prisoners rose, and employee turnover doubled last year, with nearly a third of employees leaving.

Elsewhere around the state, some inmates are sleeping on floor mats because not enough beds are available. Cells are crowded. Officers are overseeing more prisoners.

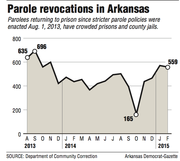

In August 2013, the state instituted stricter parole policies after the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette highlighted the case of parole absconder Darrell Dennis, who -- until the killing of Forrest Abrams -- had remained free despite 14 arrests and 10 felony charges.

The stricter policies resulted in a flood of parole revocations that, coupled with an increase in offenders sentenced to prison instead of probation, surpassed capacity at the Arkansas Department of Correction by thousands of prisoners and shifted the burden of holding the overflow prisoners to county jails.

That shift has created problems in communities across Arkansas. Chief among them: There's no room in county jails to detain people who have been arrested and are awaiting hearings and trials.

In late February, Gov. Asa Hutchinson outlined a three-pronged plan for overhauling the correction system and for providing relief to county jails.

Two of his proposals were for long-term investments to reduce prison populations and recidivism -- when people re-offend and return to prison -- and eventually, the prisoner backlog in county jails.

The third proposal called for the addition of at least 590 beds for state inmates by the end of this year. It's similar to moves last year by Gov. Mike Beebe and the Arkansas Legislature that did not ultimately provide much relief to jails.

Senate Bill 472, which would implement Hutchinson's overall plan, was passed in the House and Senate and was signed into law Thursday.

High turnover

An Arkansas Democrat-Gazette review of hundreds of Pulaski County jail documents and statistics shows that since state inmates became about a third of the jail's population in late 2013, jail employees have left at a higher rate. In 2014, 106 officers left, compared with 54 in 2013.

Records also show that increasing the number of inmates in the jail has coincided with more frequent reports of use of force against inmates.

Also, more inmates have fought one another, refused to comply with officers' orders and assaulted officers, according to the reports. In some cases, officers have responded by pushing inmates to the floor, pepper-spraying them and restraining them.

"We're running a penitentiary instead of a jail," Chief Deputy Mike Lowery of the Pulaski County sheriff's office said.

A few inmates have punched officers. A couple of inmates have gotten their heads cut open after being pushed to the floor by officers. In one instance, an inmate ripped a braid out of an officer's head during a confrontation that sent her bleeding to the hospital.

Officer and inmate injuries related to uses of force spiked in 2013, when state inmates increased to about a third of the jail's population. And, reports on uses of force didn't drastically decrease in 2014, when crowding was controlled by "closing" the jail to most nonviolent, nonfelony offenders.

Since late last summer when the state, through a contract with Pulaski County, opened 175 prison beds in a formerly empty satellite building of the jail, the lockup has closed to nonviolent offenders only once and has been open since Oct. 6. The daily jail population now hovers close to capacity -- 1,210 inmates. Reports on use of force from Oct. 6-Dec. 31 did not decrease in frequency.

Beyond uses of force, several prisoners have written to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, complaining about insufficient food, supplies, medical care and officers available to respond to inmates' needs. Some said they hesitate to file grievances with the jail for fear of how detention officers will react.

"There are times when inmates kick, yell and beat the door for a deputy to no avail," wrote Steven Bonds, now in the state Department of Correction for fraudulent use of a credit card. "What if a medical emergency occurs? Left for dead!"

As an example, one prisoner severely beat another last year, leaving him in a pool of blood.

"When I walked outside, there were a lot of inmates smoking casually like nothing had took place," Deputy Nicholas Kersey wrote in the incident report on the beating. "Nobody even moved when I walked toward [the victim]."

Sgt. Scott Hazel, who has worked in the jail for three years, said the crowding has created a volatile environment.

"There's a direct correlation between when it comes to overcrowding detention and use of force because tempers are rising, people are getting frustrated, getting frustrated and irritated with one another, having to live in those conditions."

Hazel said many new officers leave because the job is more stressful than they thought it would be.

Lt. Matthew Briggs said the intake area -- where prisoners enter the building and are booked and processed into the jail -- also had more violent incidents in 2014 because of a backup in the cells there.

"Those are really powder-keg-type environments down there," said Briggs, a supervisor who has worked at the jail for 12 years.

In addition to high turnover, staffing at the jail has been stretched thin by employee medical leaves, vacations and hospital supervision of inmates. Roving officers -- who are not assigned to specific units and are available in case of emergencies -- can be in short supply, which leaves officers with some difficult choices.

"It pulls us to where we now have to decide order of importance," Hazel said.

And the situation inside the jail can affect what happens outside it. For example, for 105 days last year, the Pulaski County jail was so full that it "closed," meaning it refused to accept most nonviolent, nonfelony offenders.

"We have to be selective about who we keep, and that's not a good situation," Sheriff Doc Holladay said.

In 2014, the jail accepted 22,790 inmates, nearly 4,000 fewer than in 2013 and the lowest number since 2011, when the jail was closed to most nonviolent, nonfelony offenders for the entire year.

Not jailing everyone the courts send for detention, "is not respectful of the courts. It's not meeting the needs of the law enforcement in this county," Holladay said. "But it's the situation we're in because I can't just hold the doors open to everybody and continue to let the population go unchecked, because the next thing you know federal court will be here saying, 'Let us run this for you.' I don't want that, and nobody else does."

ACROSS THE STATE

Arkansas' jail standards are written as minimum standards and are not strict targets for jails, according to J. Sterling Penix, coordinator of the Criminal Detention Facilities Review Committees, and Ronnie Baldwin, Arkansas Sheriffs' Association executive director. That's because the sizes of counties, their jails and their budgets vary too widely to have a uniform standard, Baldwin said.

State jail standards don't specifically prohibit inmates from sleeping on floors or require certain staffing levels for certain inmate populations. And housing state inmates is nothing new to county jails, although sheriffs say the current state prisoner levels are unusual.

"We've got sheriffs that will tell you those state inmates cause the majority of their problems," Baldwin said, adding, "Those that are awaiting a trial will be pretty much on their best behavior, usually."

"It puts our personnel in a very, very dangerous place ... to have to supervise more people," Baldwin said.

Penix agreed that more prisoners can make operations more difficult in a jail.

"Why is the amount of students limited to one teacher? Manageability," Baldwin said. "We don't have that luxury. ... It's a risk factor for our jail staff. I mean it's a dangerous situation."

Sheriff's office officials have said that some state prisoners act up specifically to get sent to prison, where they can get more services and privileges.

Department of Correction spokesman Cathy Frye said the department tries to prioritize which state prisoners it moves first out of jails. Ones with medical conditions that jails can't handle move first, for example. After that, the state tries to take prisoners who are considered troublesome.

Frye said the differences between state prisons and county jails are mainly in what the facilities are designed to do and who they are designed to detain.

"It's a completely different environment," she said of the two types of lockups.

"We just have a little bit more flexibility when it comes to our [prison] systems," she said, noting that the state has maximum- and minimum-security lockups. Frye also said the prison system has numerous buildings and so is better able to separate inmates who don't get along. Jails don't normally have the facilities to do that.

A jail typically consists of just one building with a few pods for separating inmates.

"If that pod is full, where are you going to put them? Get bed mats and sleep on the floor," said Baxter County Sheriff John Montgomery, who is first vice president of the sheriffs' association and will be president later this year.

Sebastian County Sheriff Bill Hollenbeck said assaults on detention officers have increased in his county's jail, as well.

"Whenever you put a large number of people in a small environment, we all know that becomes dangerous," Hollenbeck said.

The Sebastian County jail is built to hold up to 356 inmates, but Hollenbeck said it frequently has more than 400.

In Washington County, jail administrator Maj. Randall Denzer said his jail also has seen more fights among prisoners. "It's a safety and security issue for everybody there," Denzer said. He added that crowding has meant that prisoners in that lockup sleep on the floor sometimes.

And, he said, in addition to the crowding and stress for inmates and officers, holding the state's prisoners has caused the county financial difficulties. This winter the state was behind by as much as $1 million in reimbursing the county for holding those prisoners.

Moving forward

Denzer, Holladay and Montgomery are among officials who are optimistic about Hutchinson's efforts to curb prison recidivism, which in the long-run could reduce the number of state prisoners in county jails.

Officials noted that the governor's plan takes a long view, however, and would take a while to have a serious impact on jails.

"I'm extremely excited that the governor has taken [the] initiative to roll out his plan," Hollenbeck said, adding, "I do know that that result is going to take time."

The Arkansas Sheriffs' Association is "ecstatic" about the legislation, Baldwin said.

"We don't know if it's going to work," he said. "At least we are taking some steps forward."

Association of Arkansas Counties Communications Director Scott Perkins said that organization's leaders are also "cautiously optimistic" about the impact on county jails and are glad to see change in the criminal justice system.

One part of Hutchinson's prison plan offered short-term relief to jails by opening 590 additional beds by the end of this year and possibly 200 more if county jails enter into agreements with the state to expand their jails specifically to house certain state inmates. Lawrence County officials have already expressed interest in that idea.

State Sen. Jeremy Hutchinson, R-Little Rock, who is the governor's nephew, sponsored the legislation that would implement the governor's overall plan.

He said as many as 1,000 beds -- not including those that could come from jail expansions -- could open in the correctional system within months of the plan's implementation. He was including beds that would be freed up by sending offenders to rehabilitation facilities.

"I think it will be a major impact on jail overcrowding in the short term," Jeremy Hutchinson said. "Long-term, I think it'll be even more significant."

Last summer, Beebe urged the Legislature to appropriate $6.2 million to open 604 beds in different facilities across the state to alleviate a backlog of about 2,500 state inmates in county jails. Before that, the Legislature approved $3.1 million during its fiscal session for 350 prison beds.

The Correction Department actually opened 1,014 beds with those funds. The backlog eased briefly but later increased.

In recent weeks, more than 2,500 Correction Department prisoners have been listed as waiting for space to open in state lockups. However, at the end of March nearly 300 inmates were moved to a lockup in Bowie County, Texas, as part of Gov. Hutchinson's plan. That helped decrease the number of state prisoners in county jails to 2,229 as of Friday.

Gov. Hutchinson said measures taken last year to reduce the county-jail backlog weren't as effective as hoped because the "bubble" in parole revocations continued. He said he believes the number of parole revocations will decrease in the future.

However, Department of Community Correction statistics show that parole revocations have remained steady -- averaging 439 each month -- since December 2013.

But, during the latter part of 2013, that average rose to 622 parolees for a period four months.

"We're not seeing what we were from that summer through that December of 2013, but it's still much higher than it used to be," Frye said of the increase in parole revocations.

She said the Correction Department expects continued growth in the population it supervises, with young offenders getting longer sentences, adding that department officials sympathize with county officials.

"They're frustrated, and we completely understand," Frye said.

SundayMonday on 04/05/2015