LONDON -- Two Americans and a German won the Nobel Prize in chemistry Wednesday for work that allows optical microscopes to study cells in the tiniest molecular detail, aiding in research of diseases such as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's.

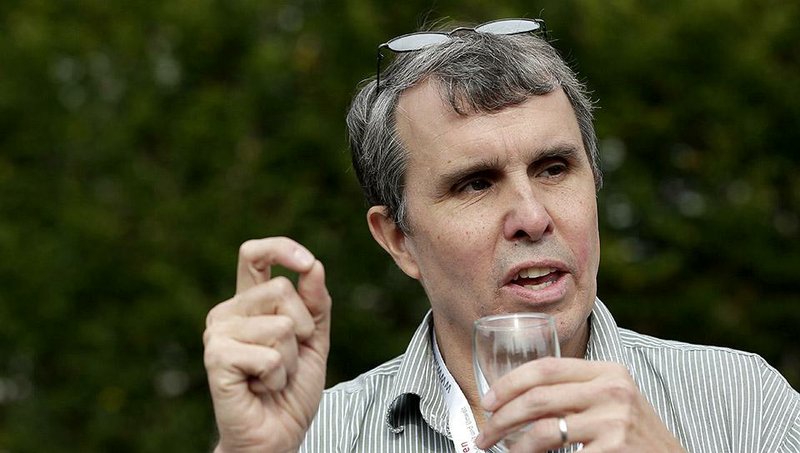

Eric Betzig, 54, of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; Stefan Hell, 51, of the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry; and William Moerner, 61, of Stanford University will share the $1.1 million award for their work on a super-resolved fluorescence microscopy, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said at a news conference Wednesday in Stockholm.

"This prize is about seeing," said Maans Ehrenberg, a professor of molecular biology at Uppsala University in Sweden and a member of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry. "The laureates have expanded what we can see with light microscopy from bacteria down to really small molecules."

Optical microscopes use visible light, which doesn't damage its subject. Electron microscopes, which can examine even smaller objects, require chemical preparation of the subject and can't be used on living organisms.

In fluorescent microscopy, proteins and other cell components are marked with luminescent molecules. It allows scientists to see molecules create synapses between nerve cells in the brain, as well as monitor the progress of proteins involved in diseases as they clump together, the academy said in a statement.

"Due to their achievements, the optical microscope can now peer into the nanoworld," the academy said. "Today, nanoscopy is used worldwide and new knowledge of greatest benefit to mankind is produced on a daily basis."

Hell, who works in Goettingen, Germany, developed a microscopy method in 2000 using two laser beams, one to stimulate fluorescent molecules to glow and another to cancel out all fluorescence except for that in a nanometer-size volume, the academy said. A nanometer is 1-billionth of a meter. Scanning over a sample results in an image with a much better resolution than scientists had thought possible.

Scientists long believed it was impossible to study living cells in microscopic detail, and optical pioneer Ernst Abbe in 1873 said the maximum resolution for traditional microscopes was 200 nanometers, a limit known as the diffraction barrier.

"The scientific community wasn't very receptive to the idea of overcoming the diffraction barrier," Hell said. "The barrier has been around since 1873. I couldn't figure out a serious reason in physics and chemistry why this wouldn't work."

Betzig and Moerner, working separately, produced the groundwork for a second method known as single-molecule microscopy, in which the fluorescence of individual molecules can be turned on and off. Scientists take images of the same area multiple times, letting just a few molecules glow each time. They then superimpose the images, yielding a denser picture at the nanolevel.

Moerner, who in 1989 was the first scientist to measure the light absorption of a single molecule, discovered in 1997 that the fluorescence of a protein isolated from jellyfish could be turned on and off. He then created a gel with the glowing protein spread across it.

In 2006, Betzig, who spent seven years out of academia working for his father's Michigan machine tool company, put Moerner's theory to practice for the first time, using the glowing proteins to illuminate the membrane surrounding the lysosome of a cell. Betzig now works at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's research campus in Ashburn, Va., which he joined in 2005.

Moerner is the 22nd researcher in the sciences or economics from Stanford to win a Nobel, according to the Nobel Foundation's website. The tally that doesn't include university alumni or peace and literature winners. The number trails only the 34 won by Harvard University researchers. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute has won seven.

Annual prizes for achievements in physics, chemistry, medicine, peace and literature were established in the will of Alfred Nobel, the Swedish inventor of dynamite, who died in 1896. The Nobel Foundation was established in 1900, and the prizes were first handed out the next year.

Three Japan-born scientists -- Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura -- won the physics Nobel on Tuesday for inventing energy-saving LED lights.

Information for this article was contributed by Makiko Kitamura of Bloomberg News.

A Section on 10/09/2014