Dawn had yet to lighten the sky May 21 when investigators believe a woman and at least one man came to Brock Atkins' rural Tontitown home near the northeast edge of the Ozark National Forest. The woman, Leann Frazier, was dead by sunrise.

Atkins, a slight 19-year-old charged with capital murder, told investigators he was falsely accused of stealing methamphetamine and was ordered by another man to kill Frazier or be killed himself, according to court documents.

At a Glance

Methamphetamine Effects

Short-term:

• Dopamine, a neurotransmitter related to pleasure and reward, surges in the brain.

• The high can last several hours, bringing increased focus and energy.

• Addiction can take as few as one or two uses.

Long-term:

• Health deteriorates as self-care and other priorities become secondary to the high. Weight loss, skin sores and “meth mouth” can result.

• The brain’s ability to process pleasure without the drug diminishes.

• Delusions, paranoia and violent behavior become more likely.

Source: Staff Report

Detectives believe Lewis Anthony Hedges Jr. suspected the woman was a "snitch" to police and encouraged Atkins to kill her. Hedges pleaded not guilty Wednesday to being an accomplice to capital murder.

The common motive: meth, a highly addictive stimulant that brings several hours of an all-consuming high and still has a foothold in Northwest Arkansas.

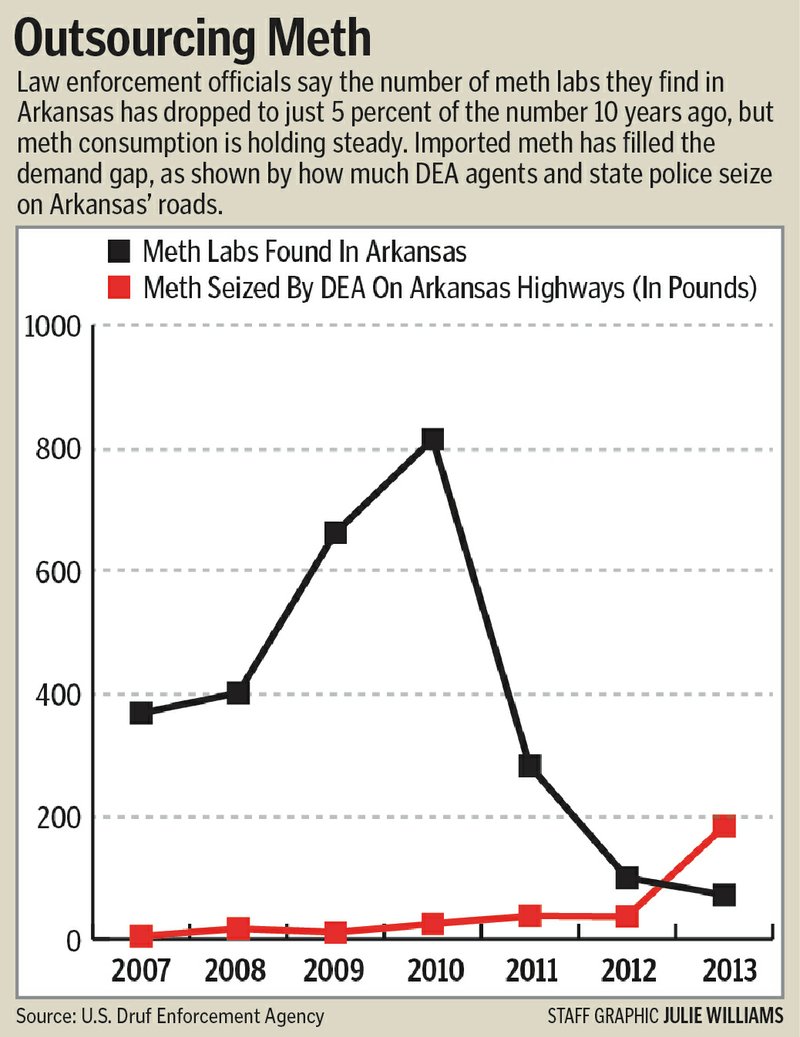

Ozarks meth production today is a small fraction of its heyday in 2004, when Arkansas law enforcement found more than 1,300 labs. Last year, 72 labs were reported by the Drug Enforcement Agency, often big enough for personal use only.

Despite this, law enforcement officials and others across the area say use of the drug is as high as ever. Related killings, accidents and trafficking rings found each year back them up.

"I don't really feel like it's on the decline at all," said Sgt. Jason French, operations coordinator with the 4th Judicial District Drug Task Force, which includes officers from most Washington County towns. "We see it in large quantities here in Northwest Arkansas."

The task force has seized about a pound of the drug so far this year -- enough for more than a thousand hits and comparable to 2004 levels. Benton County doesn't have its own task force, but Sheriff's Office deputies have seized almost as much, a spokeswoman said.

A Long Battle

Chemists first synthesized meth a century ago, but its production exploded in the 1990s and 2000s after cooks found ways to make it in smaller labs with household ingredients.

These methods transform the decongestant pseudoephedrine into meth by removing a single atom from each molecule of the medicine.

Labs spread like fire after this development, especially in the forested hills of the Ozarks and the Appalachians. They peaked in 2004, when the DEA recorded almost 25,000 labs nationwide.

Addicts often began caring more about the next high than their children or physical health. Long-term use can cause delusions, paranoia and aggression. The labs were dangerous, costly and time-consuming to clean up.

"You stop eating, you stop sleeping," said Circuit Judge Cristi Beaumont, drug court judge for the 4th District, which includes Madison County. "It starts eating away at yourself."

In 2005, the federal government followed the lead of several states and sent pseudoephedrine behind pharmacy counters, its purchases limited and tracked. Labs nationwide fell by three-fourths in two years.

It wasn't long before they crept back. Cooks embraced the new "one-pot" or "shake and bake" method, allowing production in minutes in soda bottles, according to a 2013 report from the Government Accountability Office. Labs again surged, doubling in Arkansas from a low of 368 in 2007 to more than 800 in 2010.

In 2011, Arkansas passed its own law saying anyone who wanted to buy pseudoephedrine needed a prescription or a state driver's license. Walmart went further, stopping all nonprescription sales in the state. The number of labs plummeted to fewer than one per county on average.

That means less time and money spent cleaning and less danger to neighbors and officers, officials agreed.

"We're to a point now where I can't tell you the last time I prosecuted an anhydrous ammonia or red phosphorous lab," said David Reading, deputy prosecutor for Benton County, referring to the larger labs. "As far as possession of meth and sale of meth, those cases have stayed pretty constant. I haven't seen those cases dip down since 2006."

Outsourcing Production

Traffickers now import hundreds of pounds of meth from Mexico, the Southwest and elsewhere, officials said.

For example, the state DEA and Arkansas State Police in 2007 seized about 5 pounds of meth during highway stops, DEA Special Agent Mike Davis said. By 2013, that number swelled to 184, enough for hundreds of thousands of hits.

"With us having the two main interstates like 40 and 30, and of course Highway 59, we're getting a lot of meth coming through Arkansas, destined for Arkansas and passing through," Davis said, referring to roadways that connect Arkansas to San Diego, Dallas and Tennessee, another meth-heavy state.

The increase isn't because of more officers, he added. Meth is on the move.

"It's still the No. 1 abused drug in Arkansas," Davis said, adding the state's center and northern corners are hotspots. "It's our main threat."

French, with the drug task force, said about 1 percent of the meth detectives have found this year has been in homemade powder form. The rest has been "ice" or "crystal" from much larger Mexican labs.

The varieties' relative potency depends on the cook, French added, but imported meth has the advantage of lower costs and risk.

The number of users is unclear. Hundreds of inmates are being held in Benton and Washington county jails on possession charges, but how many arrests are related to meth specifically is unclear because the charges don't specify which drug. At least half of the 350 people in the counties' drug courts were arrested in connection with meth, their judges said.

Nationwide, more than a million people use meth per year, according to 2012 estimates from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Proportionately, Arkansas is home to at least 10,000 of them.

Users have left their mark, violent and otherwise. From summer 2012 to summer 2013, about 100 babies in Arkansas were born to -- and taken from -- mothers who tested positive for meth, according to the Department of Human Services.

Besides the Tontitown stabbing, at least three other people have been killed in Washington County in connection with the drug in the past decade. They include Ronnie Lee Bradley, who was beaten to death two years ago by a man who'd been taking meth for several days, and Kevin Benish, who was shot to death in Greenland by his meth-making partner in 2004.

In Benton County, meanwhile, more than a dozen dealers have been arrested in the past year, including 11 in a Mexico-based operation in Siloam Springs and three others in Bella Vista with 200 one-pot labs.

"We still have a problem with methamphetamine here," said Scott Vanatta, a Bella Vista patrol officer. Most of the meth found there was imported from Missouri instead of Mexico, he said.

Cleaning Up

Courts often impose decades-long prison sentences for drug manufacturing and violence, which some officials said feed a cycle of drug use and crime. Drug court and private counselors in Benton and Washington counties instead work with dozens of users, using detox, behavioral therapy and, if necessary, jail time to help people get clean and stay clean.

The process is tough, said Michelle Barrett with the Benton County drug court, an austere brick building in Bentonville with large windows and high fences. Barrett is one of the court's three substance abuse counselors.

Many users begin meth thinking they'll use it sparingly for the energy or weight loss, she said, and find themselves addicted. Meth withdrawal, on the other hand, brings depression and lethargy.

"You don't want to live like that, either, and you know what will fix it: just a little bit of meth," Barrett said. "It does take a good year -- a year to 18 months -- for your body to get balanced out, so to speak."

Anyone can become a user, French said, despite stereotypes of backwoods poverty. He pointed to Justine McDuffie, 44, who worked as a substitute teacher in Fayetteville before being arrested in March in connection with possession and intent to deliver meth. Her trial is set to begin July 8.

"You have people from unfortunately all walks of life that seem to get into it -- all races, all age groups," French said.

The majority of drug court graduates don't get re-arrested, Barrett said, a sign of the program's success. Beaumont said court counselors have proved successful nationwide and more of them may help the persistent problem. She's working on adding a fourth counselor or psychiatrist to her court.

"I think drug courts are the way to stop it," Beaumont said. "If you stop the need, the dealers don't have anyone to sell to."

NW News on 06/15/2014