DETROIT - It wasn’t easy making Detroit the largest U.S. city to file for bankruptcy protection, but it was the right decision, Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder said Sunday as he, the city’s mayor and its emergency manager made the television talk show rounds.

Snyder, a Republican, gave his blessing to emergency manager Kevyn Orr’s decision to file for bankruptcy for Detroit on Thursday.

“We looked through every other viable option,” Snyder said on CBS’ Face the Nation.

Snyder said that the bondholders of the city of Detroit should expect to be “part of the process” of the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history.

“Realistically, if you step back, if you were lending to the city of Detroit in the last few years, didn’t you understand there were major issues and problems?” Snyder asked on the program. “Look at the yields they’re obtaining compared to other bonds. They were getting a premium.”

Detroit filed for bankruptcy July 18 after decades of decline left it too poor to pay billions of dollars owed to bondholders, retired police officers and current city workers.

The city faces about $18 billion of debt it must now restructure. The bankruptcy came after too few creditors would accept a plan offered by Orr to pay off $11.5 billion in unsecured debt with $2 billion in borrowed money - an offer that would have provided as little as 10 cents on the dollar owed. It also would have cost pensioners some benefits.

“The debt question needs to be addressed. But even more important is the accountability to the citizens of Detroit,” said Snyder. “They are not getting the services they deserve and they haven’t for a very long time. So this can has been getting kicked down the road for decades. Enough is enough and now’s the time to turn it around.”

On NBC’s Meet the Press, Snyder said if Detroit’s restructuring proves successful, the city could roar back stronger than before.

“We’re moving now on improving Detroit,” he added.

The state hired Orr in March to fix Detroit’s ballooning debt and more than $300 million budget deficit. He is a turnaround specialist and represented automaker Chrysler LLC during its successful restructuring.

Orr laid out his plans in a June meeting with debt holders, in which his team warned there was a 50-50 chance of a bankruptcy filing. The city then stopped paying $2.5 billion in unsecured debt to “conserve cash” for police, fire and other services.

Orr has said Detroit’s long term debt burden could be as much as $20 billion.

Over the past six decades, Detroit’s population has shrunk from 1.8 million to about 700,000. The city has about 10,000 active public workers and 18,000 retired ones who are still owed pension and health benefits.

The costs of health care and pension contributions over the years have outpaced the revenue Detroit was bringing in from property and business taxes and other sources. The city has been unable to make those contributions and pay current payroll and other bills.

Funds that cover retiree health coverage are underfunded by about $5.7 billion.Ones that cover pension obligations are underfunded by about $3.5 billion.

“We’re going to have a dialogue with the pension funds about what we can do,” Orr said on Fox News Sunday.

“And all we’re talking about in this restructuring is the unfunded component of those pension funds,” he said. “There have to be concessions.”

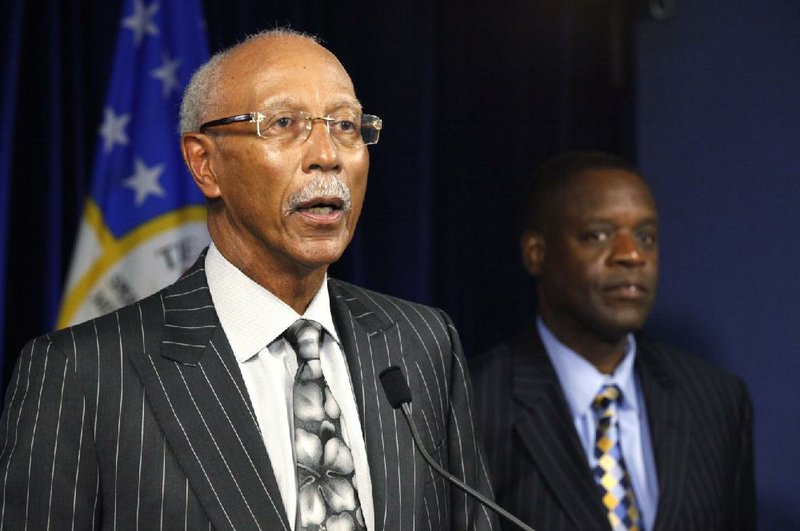

Mayor Dave Bing, a first term mayor who announced earlier this year he would not seek re-election in the fall, has been opposed to state oversight and bankruptcy. On Sunday, he told ABC’s This Week that he hopes the filing can be a new start for the city, but that he isn’t asking for a federal bailout.

“I think it’s very difficult right now to ask directly for support,” Bing said.

“Detroiters are very, very resilient people,” said Bing, a professional basketball Hall-of-Famer who spent most of his career with the NBA’s Detroit Pistons. “Detroit is a very iconic city, worldwide. Its people will fight for this and we will come back.”

But he doesn’t expect much, if any, help in the way of bailout money from the federal government.

“Now that the [bankruptcy] filing is done, we need to step back and see what’s next,” Bing said. “The president has a lot on his plate.More than 100 major urban cities are struggling and going through this. We may be the first and one of largest, but we won’t be the last.”

Orr and Snyder last week said Detroit’s crisis - 60 years in the making - would take time to resolve. Orr said the decision to enter bankruptcy came after a long build-up of resistance to his plans and what he called an olive-branch approach to creditors.

“What did we get for that?” Orr asked. “We’re getting sued, consistently.”

Detroit residents should see improvements in services within 60 days as he shores up funding, Orr said. He said he has no plans to sell assets such as the city-owned collection at the Detroit Institute of Arts.

Information for this article was contributed by Carter Dougherty and Jim Snyder of Bloomberg News and by staff members of The Associated Press.

Front Section, Pages 3 on 07/22/2013