WASHINGTON — On a fall day in 1893, an itinerant photographer began rooting through a huge collection of dust-covered glass negatives that had been stashed under the stairs of an old house on Pennsylvania Avenue.

From dingy boxes he pulled portraits of Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant and George McClellan; stark pictures of the hanging of the Lincoln assassination conspirators; and shots of the Civil War battlefield at Antietam.

It was an astonishing find.

Thirty years after the war, on the cusp of the 20th century, he had rediscovered lost work of one of the conflict’s most important and forgotten figures: Washington photographer Alexander Gardner.

Although often overshadowed by his former employer, Mathew B. Brady, Gardner was the one who actually took many of the war’s most famous, and unsettling, pictures.

It was Gardner who took the portraits of a gaunt and exhausted Lincoln weeks before his assassination.

It was Gardner who shot the ghastly photos of the dead at Antietam, history’s first photographs, experts say, of slain Americans on a battlefield.

And it was Gardner who captured the execution in July 1865 of the four bound and hooded conspirators in the assassination of Lincoln in Washington in 1865.

Although Brady is known as the father of Civil War photography, it was Gardner who took so many of the pictures that have defined the event for posterity.

Gardner “took more photos than anybody else,” said Bob Zeller, president and co-founder of the Center for Civil War Photography. “Gardner’s collection is, in terms of outdoor photographs ... the most extensive collection of Civil War photography that exists.”

When the shocking Antietam photos went on exhibit in Brady’s gallery in New York in 1862, The New York Times wrote: “Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards ... he has done something very like it.”

But Gardner had taken the pictures.

With the sesquicentennial of the Civil War, the National Portrait Gallery is preparing a major exhibit on Gardner’s work.

Scheduled for 2014, it is the capstone of the gallery’s commemoration of the war’s 150th anniversary, said Frank Goodyear, associate curator of photographs.

Gardner “is little understood,” he said. “There still is a lot of new information to be learned about who ... [he] was and the pictures that he was taking.”

Gardner died and was buried in Washington in December 1882, his career in photography past, his war over and his historic pictures of little interest to the government. His gallery at Seventh and D streets had been closed for almost a decade. And many of his negatives were scattered, sold or lost.

But Watson Porter, who had worked for Gardner years before, remembered them. In 1893, he tracked down hundreds in the house on Pennsylvania Avenue and showed them to a newspaper reporter.

“That this collection could have been for so many years hidden and neglected in the heart of a city like Washington is remarkable,” the reporter wrote in The Washington Post. “But the collection tells its own story.”

Thirty years earlier, when Gardner and assistants Timothy O’Sullivan and James Gibson reached Gettysburg shortly after the terrible battle there, most of the dead soldiers were either buried or decomposing.

So when photographers spotted the intact corpse of a young Confederate near a part of the battlefield called the Devil’s Den, they took full advantage. After shooting photos of the soldier where he had fallen, they appear to have put his body on a blanket and lugged it to a more photogenic location, according to historian William Frassanito.

The photographers placed the soldier against the backdrop of a stone fortification, probably turned his head toward the camera, and leaned a rifle beside him.

The resulting picture, one of the war’s most memorable, was largely accepted at face value until Frassanito, in his groundbreaking 1975 book Gettysburg: A Journey in Time, unearthed what probably happened.

Today such “staging” of photographs is considered unethical, but Zeller, of the photography center, said 19thcentury sensibilities were different.

Gardner “thought of himself ... as an artist,” he said. “When photography was invented, it was thought that it was going to replace art.”

Thus, a photograph could be composed, just like a painting.

Besides, Gardner already knew, from his work at Antietam, that images of the dead had impact.

The year before, Gardner had been following the Union’s Army of the Potomac when it fought the Confederates at Antietam Creek on Sept. 17, 1862, one of the deadliest battles in U.S. history.

The scene, outside Sharpsburg, Md., was horrific. The landscape was littered with dead soldiers. Along the Hagerstown turnpike, Gardner photographed clots of dead Confederates behind a wooden fence where they had been killed.

Near the tiny whitewashed Dunker Church, around which the battle had roared, he captured a tableau of dead soldiers and horses.

And in a place that has come to be called “Bloody Lane,” he photographed a sunken road filled with slain soldiers.

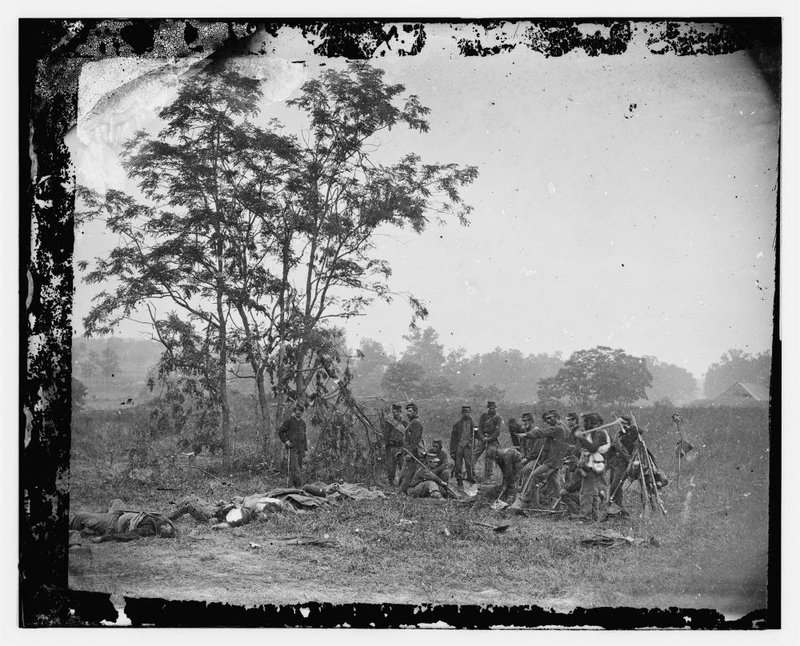

Elsewhere, he shot haunting images of a grim-looking Union burial party: 17 weather-beaten Yankees, armed with picks and shovels, pause before a line of bodies whose graves they are digging. To one side, one young soldier stares at the camera.

Such pictures, all of which were probably in Brady’s New York exhibit, had never been seen by most of the American public.

“Of all objects of horror, one would think the battlefield would stand pre-eminent,” the Times wrote. “But ... there is a terrible fascination about it that draws one near these pictures ... chained by the strange spell that dwells in dead men’s eyes.”

Gardner was 40 that September, only a few years removed from his 1856 immigration from Scotland. There he had been a jeweler, newspaper publisher and fledgling photographer, according to historian D. Mark Katz.

Gardner had gone to work for Brady, who opened an elegant Washington gallery on Pennsylvania Avenue in 1858.

By 1861, with the start of the war, Gardner had wangled an additional appointment as chief photographer on the staff of the commanding Union general, McClellan, according to Katz’s 1991 study of Gardner and his work.

Sometime after Antietam, Gardner and Brady parted ways, and Gardner opened his own Washington gallery.

In 1865, with the close of hostilities, Gardner produced a compendium of his best pictures, Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War, which remains one of the finest photo records of the conflict.

It was pricey for its time: $150. But it contained shots ofthe stone bridge at Bull Run and the Dunker Church at Antietam. There were pictures of the dead at Gettysburg and the young rebel whose body was moved.

“As mementos of the fearful struggle through which the country has just passed,” Gardner wrote in the preface, “it is confidently hoped that ... [these photos] will possess an enduring interest.”

In 1869, Gardner asked Congress to buy his photographs, describing them as national treasures, according to Katz’s history. Congress was not interested.

When Gardner died 13 years later, his estate apparently had no photographic material.

Some of his priceless negatives may have been sold as scrap glass, according to Katz’s study. Many were acquired by collectors, and in 1884 again offered for sale to the government, which remained uninterested.

When the 1893 cache was discovered, a Post reporter visited Gardner’s son, Lawrence, who said the old negatives were probably his father’s.

After that, their fate is uncertain.

In 1942, the Library of Congress acquired a trove of Gardner negatives that had been bought by a Connecticut collector and stored in a vault for a quarter-century.

But it’s unclear whether the library acquisition included the 1893 discovery.

“I am completely stumped as to where this collection of negatives fits in the picture,” said Zeller, the photo expert.

The Smithsonian said it has a few photos, apparently Gardner’s, for which there is no provenance. William Stapp, former curator of photographs at the National Portrait Gallery, said some Gardner negatives have “just vanished.”

Meanwhile, as Gardner hoped, the nation has rediscovered an “enduring interest” in his work.

The Library of Congress has digitized many of his Civil War photographs. They can be viewed online in “magical” clarity, said Helena Zinkham, head of the library’s prints and photographs division.

Zeller said a single Gardner photo of Washington, taken from the roof of the photographer’s gallery looking toward the Capitol, went up for auction last year.

It sold for $35,000.

Online: Search www.loc.gov/pictures for Alexander Gardner

Style, Pages 45 on 06/24/2012