LITTLE ROCK — Yem Prades knew he might never see his family again if he climbed aboard the boat that would take him out of Cuba, but he didn’t have much of a choice.

If he wanted a better life, he had to be on that boat.

After spending eight days in remote shacks hidden deep in the Cuban jungle, Prades wasn’t about to miss his opportunity to flee Cuba and chase his dream of playing professional baseball in the United States.

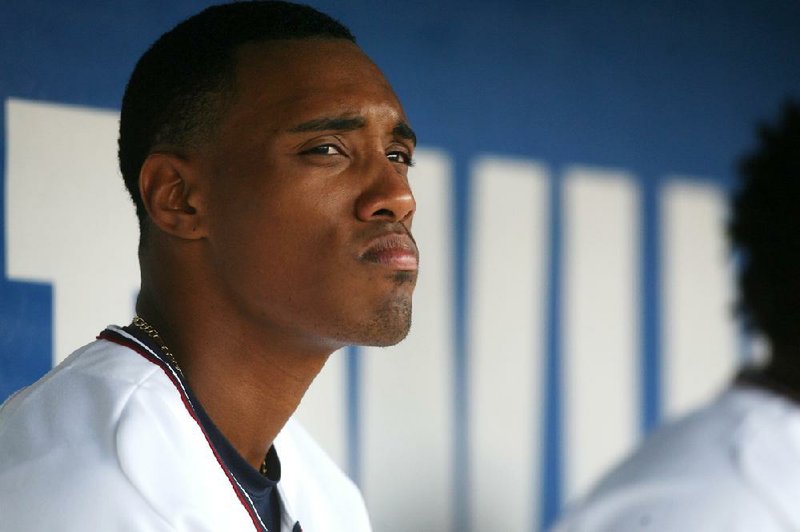

“The boat came in, and the people were just going crazy in desperation to get out,” said Prades, a 24-year-old center fielder for the Northwest Arkansas Naturals who defected four years ago. “The people were jumping in the water, trying to jump in the boat and then falling back into the water. I even jumped in the boat and fell out.

“The boat wasn’t going to wait.”

It was the beginning of a long, difficult journey that Prades hopes will one day lead to the major leagues. But all he and the 50 or so others were worried about at that moment was getting out of Cuba.

“We were just so happy,” Prades said through an interpreter during a recent interview at Arvest Ballpark in Springdale. “Everybody on the boat was just hugging each other and crying.”

Prades was aware of the dangers he faced if he were caught trying to defect, including prosecution, but the lure of a better life was too much to resist.

“Sometimes the house wasn’t holding up,” said Prades, who left his mother, father, two brothers and two sisters behind in Cuba. “It wasn’t how a person should be living their life. One day I’d have a really nice meal, but then I didn’t know about tomorrow.”

Baseball offered an opportunity for something more.

Prades had been drawn to the sport by his cousin, Miguel Caldes, a former Olympic baseball player who had helped Cuba win a silver medal in 2000. Caldes’ success had inspired Prades, but Prades was shaken later that year when Caldes died in an automobile accident at 30.

“He was the guy that really got me into baseball,” Prades said.

Prades spent three years playing in the Cuban industrial league — essentially a semipro league — where his baseball skills started to draw attention. One day a family friend approached Prades about trying to get out of the country and playing professional baseball.

Prades wasn’t sure at first.

“I wanted to get out and have a better life, but the only way to get out of Cuba was tough,” he said.

Prades continued playing in the industrial league and going about business as usual, but he had made up his mind by the time he was contacted again about fleeing Cuba.

Two men, who Prades said he’d never met, showed up at his house one day with one of his teammates. They took the players to a meeting far away from Prades’ home, where another man told them he was familiar with their baseball skills and was interested in helping them get out of the country.

Prades told the man he was interested, but that the man would have to guarantee Prades he would get out of the country. Prades knew if he were caught, his baseball career in Cuba would be jeopardized.

The men assured Prades he would be fine, and after the meeting Prades returned to his home and went back to his normal life. He received another call about a month later.

“They told us they were going to meet us in a certain location,” Prades said. “They told us to go to that spot and don’t tell anybody, not even your family. I had to tell my mom, but I didn’t say anything to my brothers or anyone else. So I met them at the place, and they took me to this house in the middle of the jungle. It was just like a room made out of wood.”

Prades and his teammate waited there for six days before anyone showed up.

“I started thinking, ‘This is not happening. It’s all lies,’ ” Prades said. “They finally came back, but they said they weren’t going to be able to do it now because there was another player who was supposed to go out with us and he got caught. So after all that, I had to go back to my family.

“After that, I just lost all hope.”

It wasn’t long before the men showed up again and convinced Prades to give it another try. He and five other players were taken to a different city this time, then were relocated with about 50 others to another shack in the jungle, this one close to the ocean.

“We were there for two days without eating or drinking or anything, just sitting there,” Prades said. “Then, about 2 a.m., they told us that the boat was coming.”

When it arrived, Prades and the rest of the group rushed on board and made the taxing two-day trip to Mexico.

“Every time I woke up, I threw up, so I just had to lay down,” Prades said. “I just laid down until I got to Mexico. We had food and water on the boat, but there were some pregnant ladies on there and some kids, so we didn’t really get to eat anything. We just left it for them.”

The difficulties didn’t end once they arrived in Mexico.

“They put me in a house with all these people that came from other places illegally,” Prades said. “It wasn’t good. In 15 days, I maybe ate three or four times.”

Prades said they were told they would be put in a van and driven to the U.S. border. The group endured a 13-hour ride in the van, but Prades said they never reached the U.S. border. Instead, they were dropped off and abandoned at a “meeting spot.” Realizing they were on their own, the group started walking and eventually everyone went their own way.

Prades and another baseball player made their way to the Gulf Coast city of Tampico, where Prades reached out to a baseball contact in the Dominican Republic. The contact, whom Prades wouldn’t name, put the players up in a hotel for two days and arranged a flight to the Dominican Republic.

The contact helped Prades get established in the Dominican Republic, where Prades spent more than three years honing his craft before catching the eye of Rene Francisco, the Kansas City Royals’ special assistant to the general manager for international operations.

The Royals gave Prades a tryout and liked what they saw, an athletic outfielder who could run and throw and showed some power at the plate. Kansas City signed Prades in March 2011 for $285,0000, a bargain price for a player of his caliber.

“The kid wanted to go and play,” Francisco said. “He didn’t want to wait around. What happens to a lot of the Cuban players is they wait and wait and wait, and sometimes it’s two or three years.”

Prades began his minor league career in May 2011 with the Royals’ advanced Class A team in Wilmington, Del., where he batted .289. But the transition off the field was tougher.

“It was hard, but I was with a host family and they helped me a little bit,” Prades said. “I understand [English] better now than I did then, but that was why it was so hard, learning the language.”

Prades said things are much easier now in his second season.

“I live in an apartment with a roommate,” he said. “I’ve got a car and can go anywhere I want.”

Prades played well enough in Wilmington to earn a promotion to Class AA Northwest Arkansas, and he has made a relatively smooth transition this season to Class AA baseball. Prades was batting .265 with 4 home runs and 19 RBI with 9 stolen bases going into Saturday night’s game against the Arkansas Travelers, and he was among six Naturals players who were named recently to the Texas League North Division All-Star team.

“Prades is pretty good now, but I’m sure he’ll have to make adjustments when he sees teams for the second and third time,” Francisco said. “He just has to get better every day and just compete. Sometimes it’s good for people to struggle, so they can go through that, because when they get to the major leagues they’re going to need that.”

The Royals have done their best to make the transition easier, which has included teaming Prades with fellow Cuban Noel Arguelles in each of his first two seasons. The two had met in the Dominican Republic, and Prades said they hit it off immediately.

Arguelles, a 22-year-old left-handed starting pitcher, defected at the World Junior Championships in Edmonton, Alberta, while competing for Cuba’s 18-and-under national team in 2008, the same year Prades fled Cuba.

Being on the same team has allowed both players to lean on each other while adjusting to living in the United States. Neither has seen his parents or siblings since leaving Cuba, and their only contact with family members in Cuba has been by telephone.

Both have become fathers within the past two years as well. Each has a wife and son in the Dominican Republic who they don’t expect to see again until after the season.

The similarities they share have helped the players bond.

“Every time you have to leave your family, it’s hard,” Arguelles said. “You’re going into a new world. You’re going to a new place you’ve never been to before that’s totally different from home.”

Arguelles said he had a hard time adjusting during his first season in the United States. Several times he felt lonely and depressed, Arguelles said, particularly when he was sidelined with a shoulder injury.

“It was hard,” Arguelles said. “It was tough for me to deal with that alone, and it all snowballed on me.”

Naturals Manager Brian Poldberg has coached several Latin American players in his five years with the club, but Prades and Arguelles are the first from Cuba. A third Cuban player in the Royals’ farm system, outfielder Roman Hernandez, is playing at Wilmington this year and could join the Naturals sometime in the next two years.

Poldberg said he understands that Cuban players face challenges others don’t when they come to the United States and how it can affect the way they perform on the field, especially young players.

“Cuba is a different culture from Venezuela and the Dominican Republic as far as coming over,” Poldberg said. “Even though they speak the same language, it’s not always that easy just to blend right in. You’re away from your family, and you might never get back to see some of them. That’s a tough thing for a young kid.”

It’s still tough for Prades, even though it’s been four years since he made it out of Cuba. He is working his way through the minor leagues quickly, and there is a chance he could achieve his dream and end up in the majors within the next two or three years.

If that day comes, he said he would love to share that moment with the family he left behind in Cuba, but he realizes that may never happen with his family still in Cuba.

“They’ve been there so long, and they know that culture,” Prades said. “They want to be here for me, they want to see me. I think if they could come here and just watch me play once, that would be enough.”

Prades glance

NAME Yem Prades TEAM Northwest Arkansas Naturals POSITION Center fielder AGE 24 (born March 8, 1988) BIRTHPLACE La Habana, Cuba HEIGHT/WEIGHT 6-2, 194 pounds BATS Right THROWS Right STATISTICS .265 batting average, 4 home runs, 19 RBI, 9 stolen bases NOTEWORTHY Defected from Cuba in 2008. ... Received a $285,000 bonus when he signed with the Kansas City Royals in March 2011. ... Hit .289 with 4 home runs, 24 RBI and 11 stolen bases with advanced Class A Wilmington last year.

Sports, Pages 21 on 06/24/2012