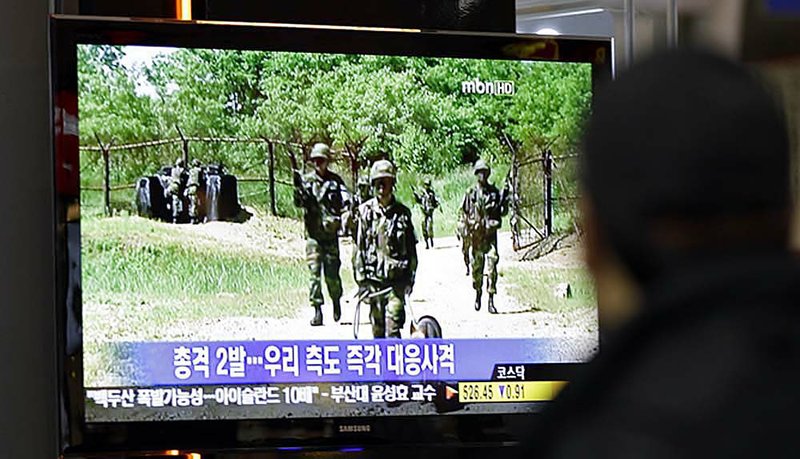

SEOUL, South Korea — North Korean troops fired two machine-gun bursts at a South Korean guard post across their heavily militarized border Friday night, and soldiers from the South returned fire with three rifle shots, a Defense Ministry official said in Seoul.

The official, Kiyheon Kwon, said the gunfire from the North was unprovoked and that a United Nations investigation team was being sent to the scene. The exchange took place in Hwacheon, a mountainous area about 70 miles northeast of Seoul.

South Korean troops along the border were placed on the highest state of alert, Kwon said, adding that “ nothing more happened” after the initial volleys. The North Korean gunfire came from a guard post about 1,400 yards away, he said.

Defense officials said they had no immediate explanation for the North Korean gunfire, which they said was the first such incident since August 2007. They said the shots had come from a 14.5mm machine gun, typically used against aircraft and light armor. The North Korean military is known to use the gun, which has an effective range of 2,000 yards.

South Korean soldiers suffered no injuries, according to an official with the Joint Chief of Staff in Seoul, who asked not to be identified because he was not autho-rized to speak to the media. There was no word from the North on either the gunfire or injuries.

North Korea was angered by Seoul’s recent refusal to engage in additional rounds of open-ended military talks, according to analysts in Seoul. Earlier Friday, the North’s official news agency, KCNA, called the rejection of the talks “an act of treachery” that would have “a catastrophic impact.”

“There was this verbal attack by the North Koreans,” said Paik Hak-soon, director of the Center for North Korean Studies at the Sejong Institute near Seoul. “The North said South Korea would get a very serious lesson from this noncooperation.

“It’s too soon to know, and maybe it’s just accidental firing, but if this proves to be intentional firing, North Korea could be trying to send a signal that they are living up to their words.”

According to South Korea’s Yonhap news agency, a team from the United Nations Command, which oversees the Korean armistice agreement, in place since 1953, will investigate Friday’s gunfire to determine whether North Korea’s military violated terms of the agreement.

The gunfire came on the eve of a highly anticipated reunion of families separated by the Korean War. More than 430 South Koreans crossed into North Korea today to reunite with relatives.

The South Koreans, mostly in their 80s, were to meet with the North Koreans in the North Korean resort of Diamond Mountain for three days before returning home, according to South Korea’s Red Cross.

The reunions are emotional for Koreans, as most participants are elderly and are eager to see loved ones before they die. More than 20,800 family members have had brief reunions in face-to-face meetings or by video since a landmark inter-Korean summit in 2000. There are no mail, telephone or e-mail exchanges between ordinary citizens across the heavily fortified border.

Earlier this week, attempts to expand the reunion program foundered after Pyongyang demanded 500,000 tons of rice and 300,000 tons of fertilizer in exchange for regular gatherings. The South’s Red Cross representatives didn’t agree to the terms, and talks broke down.

South Korea also is preparing to host a summit of leaders from the Group of 20 economic powers on Nov. 11-12 in Seoul. The group includes the United States, China, Russia and the European Union.

Tensions have been strained between the two Koreas since the sinking of a South Korean warship in March, which the South has blamed on a North Korean torpedo attack. TheNorth has denied involvement in the sinking, which killed 46 sailors.

But in recent weeks the North has made diplomatic overtures that Paik characterized as “a peace offensive.”

“So intentional firing by North Korea, across the DMZ, it doesn’t make sense,” he said.

North Korea shuffled its senior leadership hierarchy last month, with the youngest son of the leader, Kim Jong Il, receiving significant political posts in the Workers’ Party.

“The most urgent thing for North Korea right now is their political stability,” Paik said. “They want a smooth power succession, a smooth transition. That’s their top priority, and anything that would have a negative impact on that would be avoided.”

In Seoul, a Defense Ministry official said the military talks proposed last week by the North did not take place because the two Koreas remain at odds over the sinking of the Cheonan. He spoke on condition of anonymity, citing internal policy.

Pyongyang had warned during military talks in late September that it could fire artillery at sites in the South where civilian activists set off helium balloons filled with leaflets condemning North Korea’s leader, pushing them across the border.

The North views the leaflets - which activists hope will persuade North Koreans to rise up against Kim - as part of psychological warfare aimed at toppling its regime. Seoul says it cannot ban its citizens from expressing their opinions.

Though a major global economy and a political leader in Asia with one of the highest standards of living in the world, the South is still technically at war with the North because their conflict ended in a truce, not a peace treaty. Tens of thousands of troops stand guard on both sides of the border dividing the Koreas.

Communist North Korea has a track record of provocations against South Korea at times of internal change, external pressure or when world attention is focused on Seoul.

“The North wants to show the world that military tension grips the Korean peninsula,” said Kim Yong-hyun, an expert on North Korean affairs at Seoul’s Dongguk University.

In 1987, a year before Seoul hosted the Summer Olympics, North Korean agents planted a bomb on a South Korean plane, killing all 115 people on board. In 2002, when South Korea was jointly hosting soccer’s World Cup along with Japan, a North Korean naval boat sank a South Korean patrol vessel near their disputed western sea border.

Analyst Lee Sang-hyun of the Sejong Institute, a private security think tank outside Seoul, agreed that the North was probably hoping to humiliate South Korean President Lee Myung-bak on the eve of the G-20. But he remained cautious about whether the firing was an isolated incident or could signal further provocations against the South.

“It’s hard to say what caused this,” Dan Pinkston, a Seoul-based expert at the International Crisis Group, said of Friday’s gunfire. “It could be a premeditated thing after the South turned down the offer for [military talks]. It could just be, you’re out there along the DMZ, there’s obscene gestures, there’s taunting. You’re isolated. So, OK, let’s squeeze off a couple rounds.” Information for this article was contributed by Mark McDonald of The New York Times, by Chico Harlan of The Washington Post and by Kwang-tae Kim of The Associated Press.

Front Section, Pages 1 on 10/30/2010