SELF PORTRAIT

Date and place of birth: April 10, 1966, Houston What’s in my CD player: The Best of Marvin Gaye My favorite book: I have several but the two that come to mind are Denmark Vesey by David Robertson and Arc of Justice by Kevin Boyle. If I had to choose another profession it would be that of a civil rights or family law attorney.

If I could change anything about myself it would be my penchant for always looking to do the next thing. I need to do a better job of enjoying the moment.

I feel lost without e-mail. One day I will write another novel.

The dish that makes me happiest is my mother’s gravy steak, rice, cabbage and corn bread.

If I won $10 million, I would establish a large endowment for our African and African-American Studies Program and other diversity programs.

If I had the opportunity to live anywhere else in the world, it would be in the Far East.

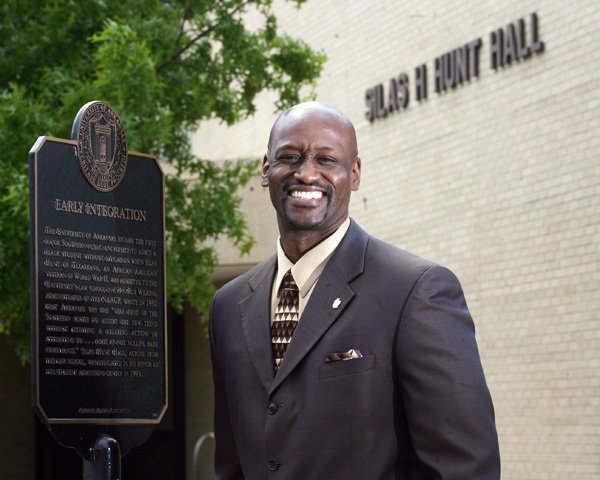

A couple of words that sum me up: persistent and compassionateFAYETTEVILLE - Charles Robinson has a unique skill set. He has mastered the art of wielding a sledgehammertype topic softly.

Robinson, who became vice provost for diversity at the University of Arkansas in July, is intent on starting and maintaining a dialogue about prejudices and divisions between races.

“You’re never going to fix the racial issues we have in this country until you dialogue and think on it critically,” Robinson says as his eyes light up and he guides his conversation to his life’s passion.

Robinson, 44, stands 6 feet 4 inches and seems to get taller with every word, as if he’s trying to physically match the immensity of the topic - fostering a pluralistic community, country and society.

As Robinson delves deeper into the conversation, his persona changes. His eyes widen, his gestures become more pronounced and his voice deepens.

“The story of Celia the slave is the perfect example,” he says, transformed into an eloquent orator.

“She was a 14-year-old female slave who had had enough of being sexually abused by her master ...”

Robinson weaves the tale of a frustrated slave who lashes out at her master, kills him, and then the repercussions. The point of the story is to elicit a reaction from his audience. It provides an opportunity to explore the differences in perspective and ultimately find a common ground for discussion.

It has taken some time to hone his craft, but Robinson is now skillful in turning people’s attention away from himself and focusing it on his mission.

“This work helps me create those opportunities,” Robinson says. “I have the chance to let students see those great African-American characters.

“Now we have to build critical masses, especially at the University of Arkansas. Growing numbers and understanding.”

Robinson’s efforts began with helping to spearhead a $1 million fundraising campaign for the diversity department. The goal was greeted with more than a few raised eyebrows, but that’s nothing new to him.

“A lot of people thought we were aiming too high,” he says. “But I believe people, even in a recession, see a need here and they’re willing to help. We just have to let them know how they can.”

Although the campaign goal isn’t yet met, Robinson recently helped secure one of the largest donations to the program so far. A perfect combination of timing and information led Fayetteville philanthropist Richard Greene to pledge $400,000 to the program over the next five years.

“Charles is an extremely capable and passionate person,” Greene says. “But he’s not sopassionate to the point that he scares you off or is overbearing. He is steady and locked on to his mission and truly believes in what he’s doing.”

Robinson’s effect on Greene is perhaps best demonstrated as the 59-year-old, 1976 UA graduate echoes Robinson’s primary message.

“Prejudices have been perpetuated in the state for a long time,” Greene says. “It oftentimes has a lot more to do with economic circumstances than race.

“Unfortunately in this state, a lot of black people are stuck in low economic situations.We can start to raise that level if we can help people take advantage of these educational opportunities. That’s where it all begins.”

OPENING DOORS

A 1984 graduate of Dulles High School in Missouri City, Texas, a suburb of Houston, Robinson says his upbringing didn’t particularly place him in the cross hairs of cultural debate. In his words, he grew up in a privileged middleclass family. His father, also named Charles, was an insurance agent for Allstate, providing the family a comfortable living.

As a teenager, Robinson worked several jobs. Chickfil-A, not his favorite job, provided him with a valuable lesson that “persistence pays off.” After two years working at the fast-food chain, he earned a $1,000 scholarship for college.

“In those days, that was a lot of money,” he says. “My mother and father kept me grounded and always stressed the importance in working for what you want.”

So that’s what he has done throughout his life and it’s what he wants for those around him.

“I believe in working hard. That’s what this diversity department is all about,” he says. “It’s not about free handouts. It’s about finding those people who really want to work but haven’t been taught how to take advantage of the opportunity to come to a school like this.”

After spending his undergraduate days at the University of Houston, where he had numerous black friends and there was black faculty, Robinson found himself alone at the graduate level at the private Rice University, also in Houston.

“It was really tough for me to adjust at Rice,” he says. “There wasn’t a good network for people of color on the graduate level. In fact, I was the only one there.

“I really wanted to quit.”

His father helped him see the value of staying at Rice.

“If you get that Rice degree, that’ll really open some doors for you,” the father told his son.

His father was right.

A STRATEGIC MOVE

Robinson’s office is tucked away in a nondescript building on the UA campus - fitting for a man adept at dodging the spotlight.

“I remember when I first came here from Houston,” he says. “I didn’t have a clue what I was getting into.”

That was 1999, and Robinson was one of UA’s “strategic hires” as officials tried to recruit a more diverse faculty.

An assistant professor, Robinson was the second black faculty member in the UA history department, following the late Nudie Williams, who joined the university in 1976 and spent 27 years there.

Robinson had taught for nine years at Houston Community College after he earned a bachelor’s degree in history at the University of Houston, a master’s degree in history at Rice and a doctorate in history back at the University of Houston.

He loves teaching. During his tenure as an associate professor of history and director of the African-American Studies program, Robinson has been awarded the Fulbright College Master Teacher Award, the Arkansas Alumni Distinguished Teacher Award and the StudentAlumni Board Teacher of the Year Award. He has also been cited for excellence and inducted into the university’s Teaching Academy. In 2006, the Black Student Association honored him with the Lonnie R. Williams Bridging Excellence Award and in January 2008, he was given the Martin Luther King Jr. Lifetime Achievement Award by the Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Planning Committee in Fayetteville.

The classroom is where Robinson saw firsthand the racial divisions he believes need to be addressed in this country.

A few days into teaching at Houston Community College, he realized something about his classroom. All the blacks sat on one side of the room and the whites on the other. A mixed-race student and a Hispanic student sat in the middle row.

“I was stunned by that,” Robinson says. “I hadn’t even noticed. But when I did, I was like, ‘Wait a minute. Let’s talk about this and figure out why we separate ourselves this way.’”

When he got to Arkansas, Robinson knew his mission was much bigger than a classroom’s seating chart. It took him a long time to adjust and get settled at the UA.

“It’s a place I always felt lacked sufficient diversity for me. But you never change the game sitting on the sidelines. If you want to change it, you have to get in it and get dirty with it.”

And get in the game he did.

In 2004, after five years at the university, Robinson accepted the chance to become director of the African-American Studies program “because it gave me a real pulpit to start talking about diversity outside of the classroom.”

PLAYING ROLE MODEL

While Robinson’s storytelling abilities have proven useful in the classroom, his ability to be straightforward has served him just as well.

Deshon Wilson, 22, a UAsenior majoring in biochemistry and biology, credits Robinson with shaping his college experience the most.

“I never had a father or a positive male role model growing up,” Wilson says.

He met Robinson at a Student African American Brotherhood event, where, he says, Robinson offered to be “a role model, mentor or whatever you need to help you get the most out of your time at the university.”

Wilson, who is also enlisted in the U.S. Army and scheduled to be deployed to Kuwait, leaned on Robinson.

“I talked to him almost every week,” he says. “He has taught me how to be a man and what it means to take responsibility for myself and my actions.”

Wilson recalls a time when Robinson had to take a stern approach.

“I remember the first test I took in his class,” he says. “I think I made a C or something like that and he told me, ‘You can do better than this. Don’t settle for being mediocre.’”

Wilson writes poetry and says Robinson has read most everything he’s written. Robinson told him he needed to apply the passion he put into poetry into everything he did.

“I tried to do that and my grades improved immediately,” he says.

John Jones, 23, who is graduating from the UA this spring with a degree in mechanical engineering, decided to pursue a master’s in higher education, in part because of Robinson’s encouragement.

When Jones’ father died in 2007, Robinson helped him deal with his emotions yet stay focused on school.

“When we talked, he would always say, ‘I’m here for you and I understand how tough this is.’ But at the same time he kept me focused on how much potential I had as a student and a leader.”

In the classroom, Robinson taught Jones a lesson that resonates through his life today.

“He made a point to spotlight people we don’t normally hear about in history classes,” Jones says. “One I remember in particular is Bayard Rustin, who worked closely with Martin Luther King Jr.

“The reason this story was so powerful for me was because I’m really interested in Dr. King’s life and I always thought he was just this selfpropelled man that did these great things on his own. But he didn’t. He had people like Rustin, who advised him but stayed behind the scenes.

“To this day, when I have to make a major decision I make sure I have a group of people to help me, Dr. Robinson being the first a lot of times,” Jones says.

EYES WIDE OPEN

Robinson has leaned heavily on his pen in his fight. Among his books are Dangerous Liaisons: Sex and Love in the Segregated South (2003) with the University of Arkansas Press and Forsaking All Others: Interracial Sex and Revenge in the 1880s South, pending publication with the University of Tennessee Press. In addition to his scholarly pursuits, Robinson has self-published a historical fiction novel, Engaging Missouri: An Epic Drama of Love, Honor and Redemption Across the Color Line (2007).

Interracial relationships are a theme in his work and one such relationship early in his life drew his attention to the country’s racial divide.

“There was this girl that I really liked in high school,” he says. “And back then I thought I had it going on pretty good. I thought I was pretty attractive, dressed OK, and I worked.

“But for some reason I could just never get this girl to commit to being my girlfriend.”

Although Robinson sensed her rebuffs had something to do with race - she was of German and Iranian descent - he didn’t fully understand the personal rejection.

The magnitude of the sociological issues finally hit him in an academic setting,in his classes in the African-American Studies program at Houston.

“Those classes really helped me see things in a social context. I finally understood that it had nothing to do with me, but socially it just wasn’t acceptable, especially to her parents,” he says.

“We talked years later and she admitted to me that that’s what it was. She didn’t want to upset her family. Her father had some very strong viewpoints on race relations and she didn’t want to have to deal with that,” he says.

Just because he understands the issue now doesn’t mean Robinson accepts it.

“That’s why we have to continue to dialogue,” he says. “We have to just keep working on these issues until we tear down these walls and they just don’t exist anymore.”

Although Robinson has spent many years examining the intricacies of interracial relationships in the South, his previous marriage was to a black woman and he is engaged to a black woman.

“My experiences as a young man did spark the desire to look into interracial relationships, especially the laws about them,” Robinson says. “But I personally always tried to make decisions based on who I connected with the best.”

He’s engaged to marry Reynelda Augustine of Fayetteville, a member of the UA administrative staff.

Robinson, who has two sons, Charles Robinson III, 16, and Jalen Robinson, 7, says he is determined to keep trying to change the world so that race won’t matter as much in their lives as it has in his.

“I tell my sons and anybody, for that matter, ‘If you’re going into that type of relationship, go into it with eyes wide open,’” Robinson says. “You’re going to have an added pressure because people will take notice of your relationship. That’s just the society we live in. But you have to follow your heart and do what you believe will make you happy.”

Northwest Profile, Pages 41 on 05/02/2010