Photography is a mysterious art that, because of its mechanical nature, some tend to dismiss. It is not exactly science and it is certainly not objective. Cameras lie all the time and moments cannot be definitively arrested. Anyone can press a shutter, yet there are still masters who see images that elude the rest of us.

It was 33 years ago the great portrait photographer Andrew Kilgore took my picture.

I don't remember why I wanted my picture taken; I'm not someone who particularly likes being photographed. It had something to do with Kilgore's reputation. I admired his work and understood he was a fine artist. For some reason it was affordable. So Andrew Kilgore took my photograph.

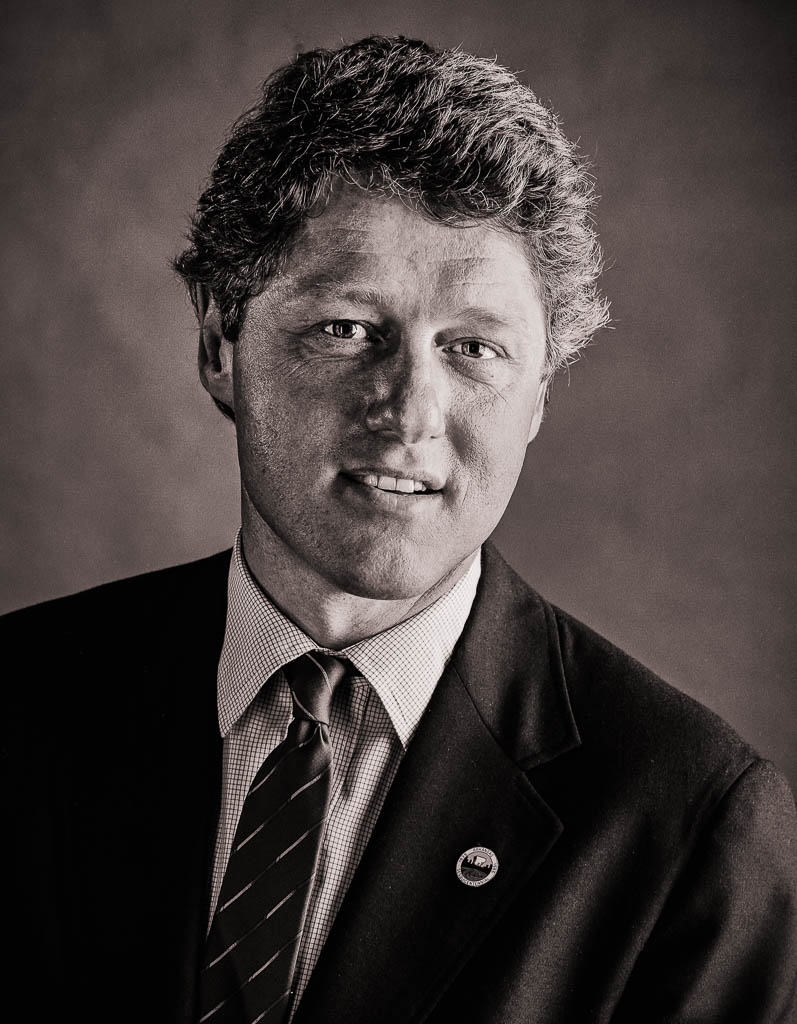

It was a brief session; he'd set up his gear and scheduled a half-dozen or more appointments for the day. I sat on a stool. A strobe light flashed a few times as we chatted a bit, and it was over. A couple of weeks later I got a proof sheet with a dozen or so images, plus Kilgore's favorite of the bunch blown up as an 8 x 10.

I hated that photograph. It hurt me to look at it.

I look somehow wayward; my eyes are lifted, my mouth is agape, and my hands are extended in what seems a gesture of supplication. I look wonderstruck and simple. The photograph did not appeal to my vanity.

I asked for a more conventional frame to be printed in which I am smiling like an anchorman, leaning forward confidently, my fingertips pressed together. I'm wearing a Boston Red Sox cap, which seems silly now but was part of my everyday armor back then. It's a strong portrait of the poseur as a young man, and hangs in the hallway outside my office, next to a spectacular photograph Kilgore took of Karen and our dog Coal some years later.

At the time, I didn't understand how the photographer could have preferred his image over the one I--the always-right customer--eventually chose.

All these years later, I think his choice was truer, and there was cowardice in my decision. I got a good photograph for sure, one that makes the young man it depicts seem self-possessed and handsome in a bland television-personality sort of way. But I could have had a work of art that revealed more about its subject than the subject was comfortable revealing.

My first job in journalism was conditional on being able to shoot competently, develop film and print photos. The only journalism classes I ever took were in photography, and there were a couple of years when the most expensive objects I owned were a brace of Nikon F2s.

I still shoot intentionally, though most of the time I keep my good cameras in their bags and rely on my phone and iPad, which are perfectly serviceable for the work I do. (And capable, in their own way, of serving a particular kind of artistic impulse.)

Most people think they are pretty good photographers, in the same way that most people think they are pretty good drivers. Technology makes it easy to point and shoot, to steer and brake. The movies taught us how to frame shots; most people probably acquire a sense of composition by being exposed to the way professional camerapeople frame the world. There are lots of nice images popping up in Facebook feeds.

But Kilgore does not take nice photos. His work can be beautiful, and is always respectful of his subjects' humanity. It's also insistently interrogatory, black-and-white studies of often stigmatized and unseen souls.

What conveys in an Andrew Kilgore photograph is not so much the way light can drape and dazzle, but how human beings might connect. His camera looks deep and hard, and his people--Kilgore's beloved--gaze back into our surrogate eye with trust and longing. Technical expertise aside, it's Kilgore's empathy that makes his work so rewarding.

When I heard that 100 of Kilgore's portraits are being shown at the Walton Arts Center (through March 19), I determined to go. I haven't made it yet because life is busy, but I will, because Kilgore is in the first rank of American--not just Arkansan--artists, and his portraits are singular in their gentle and convincing power.

. . .

It is less likely that I'll make it to Hoover, Ala., to see an exhibition of Art Meripol's concert photos. Meripol was a staff photographer for the Arkansas Gazette in the '80s and covered hundreds of concerts across the mid-South.

He's a friend and former colleague of Karen's. I follow his Facebook feed and have seen a lot of his concert photos. They are terrific. He's taken some of the best action shots of Bruce Springsteen and B.B. King I've ever seen. (Karen has a stash of Meripol's photos, one of the perks of working with artists at newspapers. We also have John Deering paintings and images by other shooters we've worked with.)

Though I've covered and attended hundreds of concerts in the same time period as Meripol (we were at a lot of the same shows), I've never shot one, though it's not dissimilar to shooting a sporting event. (Anticipation is key; by the time you see the shot, it's too late.)

The job is compounded by the brief window that's allowed photographers covering concerts; at big venues, being allowed to shoot during the first three songs is generous.

Meripol's show, at Aldridge Gardens in Hoover through March 5, consists of some 38 mounted images, with about 50 more prints visitors can rifle through. (Admission to the show is free, and photos are for sale.)

Were this the '80s, I'd be on the road to Hoover to see this exhibition this weekend. Since it's not, I encourage one of our local galleries to connect with Meripol in order to bring the exhibit to Little Rock, where many of the photos were taken.