- When he shook it and he rang like silver

- And he shook it and it shined like gold

- And he shook it and he beat that steam drill, baby

- Well bless my soul

- — Gillian Welch, "Elvis Presley Blues"

In her song "Elvis Presley Blues," neo-traditional singer-songwriter Gillian Welch compares the subject of the song with folkloric hero John Henry, the steel drivin' man who allegedly raced against a steam-powered rock drilling machine, driving a steel spike into rocks with his hammer to make a hole in which explosives could be packed.

The legend holds that John Henry won the race but died immediately afterward, his hammer in his hand. The lesson seems clear: The human spirit can prevail in battle but the war against the inevitable is long and lost. Our machines will one day eat us, the biggest hearts will explode, and yet we always side with fragile humanity against the inhuman inevitable.

Welch's song starts with the line: "I was thinking that night about Elvis, the day he died."

I remember that day: Aug. 16, 1977. I was working in a sporting goods store. We ironed up some black T-shirts with Elvis' photo on them and sold a few to the yokels. Elvis was a joke to us then, a sellout whose fans embarrassed us with their hyperbole and earnestness.

My parents told me the first song I ever responded to was his version of "Old Shep," a maudlin song written by Red Foley and Arthur Willis about Hoover, the German shepherd that was Foley's childhood companion.

The story is that a neighbor poisoned Hoover and that — as the lyrics suggest — the dog had to be put down. Foley first recorded the song in 1935 and re-recorded it when he switched record labels in 1941. Hank Williams recorded a cover version in 1942. Foley recorded it for a third time in 1946, by which time it was considered a mawkish country classic.

The 10-year-old Elvis, famously dressed like a cowboy and standing on a chair to reach the microphone, sang the song without accompaniment in a contest at the Mississippi-Alabama Fair and Dairy Show in October 1945. He won fifth place and was presented with a $5 bill and a pass that allowed him to ride all the rides for free. Some of his classmates at Memphis' L.C. Humes High School remember him singing the song at a National Honor Society talent show in 1951.

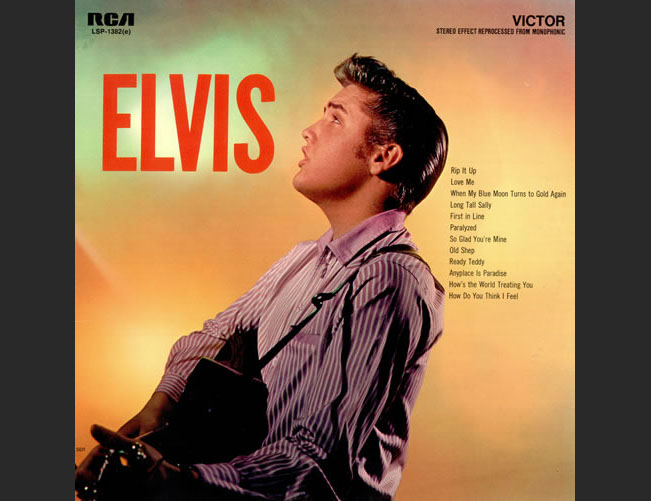

The version I knew as a little kid was recorded Sept. 2, 1956, at Radio Recorders studio in Hollywood and released about six weeks later on "Elvis," the second RCA album. The song is a little out of character for early Elvis in that it's a turgid track that runs for more than four minutes — every other track on the album save one clocks in at under three minutes. It's not hard to imagine that it was included to fill out the album.

The story is that Elvis sat down at the piano and ran through the song a few times, with the fifth take becoming the album version. (In the U.K., the first take was used.) While the RCA archives don't have much information about the session, it sounds like Elvis played the song on piano with bassist Bill Black, electric guitarist Scotty Moore and drummer D.J. Fontana following along.

This makes sense because Elvis was the de facto producer of these sessions — Steve Sholes, the RCA executive who is listed as the album's producer, handled paperwork, but allowed Elvis to choose the songs and work up arrangements with the band.

Elvis was familiar with "Old Shep"; maybe he saw it as a kind of good luck charm. He started playing it, the band fell in behind him, and later the Jordanaires — the vocal quartet that began working with Elvis after he moved from Sun Records to RCA — overdubbed their harmonies.

We can presume there were overdubs, because most sources list Elvis as playing acoustic guitar as well as piano on the song. In 1984, Gordon Stoker, who sang tenor with the Jordanaires, told Dutch Elvis scholar Jan-Erik Kjeseth that he played most of the piano on those sessions, though he wasn't sure whether he played on "Old Shep."

A lot of people would argue "Old Shep" is the weakest song on "Elvis." I think they're right about that.

But the song catches me in a weird place — it's about a dog dying, and dogs do die and that is sad, but it means something else. It is about that tender time before I went to school when I could somehow conflate Elvis Presley with my Uncle Roy — they were both in the U.S. Army and Roy, like Elvis, had a Harley-Davidson motorcycle and a dash of glamour — and believe that Nipper, the RCA trademark who sat listening at the Victrola for "his master's voice," was actually Shep.

HISTORIC ELVIS

I hear "Old Shep" these days and feel tender for the historic Elvis, a kid who was dating Natalie Wood at the time he recorded the song. She was at those sessions; she and her friend and "Rebel Without a Cause" co-star Nick Adams showed up at Radio Recorders the day after Elvis recorded "Old Shep," in violation of the studio's "no visitors" policy.

Sholes and Col. Tom Parker may not have been happy to see them; it took Elvis 27 takes to get through the first song slated for the session, the ballad "First in Line." (While Sholes and Elvis had hoped to get six new songs on tape that day, the struggles with "First in Line" caused them to rethink their strategy. With only a few hours left in the studio — RCA had booked three days for recording, and Elvis was due back on the set of his film debut, "Love Me Tender," the next day anyway — they elected to fill out the new record with covers of Little Richard songs that had been featured in the band's live act.)

The romance between Elvis and Wood might have all been a publicity arrangement, designed to synergize the careers of two of the hottest stars on the planet in late 1956; but there's a real possibility that he was genuinely smitten with her. As an 8-year-old, Wood had starred in "Miracle on 34th Street," a movie that the 10-year-old Elvis watched again and again. Some Elvis authors have written that he wanted to marry her, and that was his intention when he took her to Memphis to meet his parents.

But, the story goes that his mother, Gladys, wrecked things before they really got started. She did not approve of Wood's flimsy nightgowns or her movie-star ways, the barely submerged sexual aggressiveness of the Hollywood trollop.

For her part, Wood was creeped out by the physical closeness of mother and son. Elvis sat on Gladys' lap. Maybe Elvis didn't want to touch Natalie. She arranged to have her mother call her home on some fake family emergency. You can believe all the gossip you want.

NICE SOUTHERN BOY

A lot of it makes Elvis sound like a nice Southern boy with manners and deep-seated insecurities that had to do with his socioeconomic standing and what we'd probably now call imposter syndrome.

Sam Phillips once said that Elvis reminded him of old Black men he knew who'd been beaten down by a racist society. Lots of his classmates at Humes High would later testify that teenage Elvis was shy and diffident, religious, polite but "dirty" — one of the high school's poorest kids, with dirty hair that was always hanging in his eyes.

But not, as the myth goes, a "sissy."

He was on the school's boxing team for a while until the team's coach Walt Doxey matched him up against a welterweight named Sanford "Sambo" Barrom — an accomplished Golden Gloves fighter — and Barrom bloodied his nose. He had to quit the school's football team because it interfered with his after-school work. (Elvis wasn't fast, a teammate remembered; he had those moves — those hips swiveled.)

In his junior and senior year he developed more of a sense of himself and grew his hair and sideburns and started wearing pink jackets and yellow slacks, but the only kid his classmates remembered bullying him was Red West, who'd go on to be part of Elvis' Memphis Mafia as his confidant and bodyguard.

Apparently Red West bullied everyone.

Classmate George Grimes remembers that when Elvis and others who'd taken part in a Humes High talent show made a field trip to the University of Mississippi, some of the students there gave Elvis grief.

"I saw a bunch of students hassling Elvis about his hair and odd clothes and I didn't take up for him," Grimes wrote on an internet message board. "I always felt guilty about that."

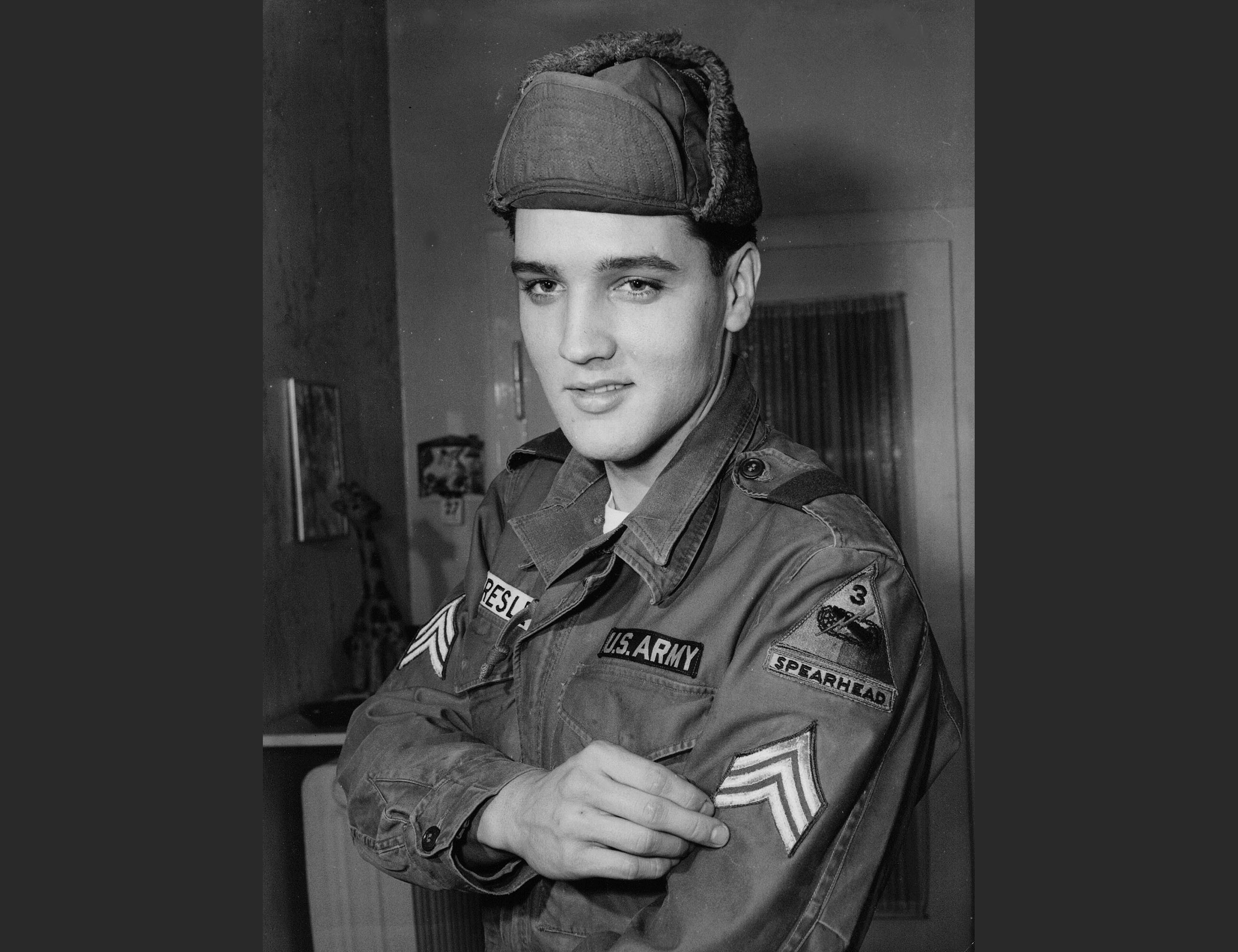

Elvis Presley is seen in this Jan. 21, 1960, file photo taken in Bad Nauheim while serving for the U.S. Army in Germany. (AP Photo) A GOOD SOLDIER

Elvis Presley is seen in this Jan. 21, 1960, file photo taken in Bad Nauheim while serving for the U.S. Army in Germany. (AP Photo) A GOOD SOLDIER

Elvis was a good soldier, well liked by his comrades. He didn't ask for special treatment — Colonel Parker didn't want him performing anyway. He did his job, served his tour. Maybe he thought it was the end of the special life he'd enjoyed for four years; maybe he thought he was going to have to work at something else after he got out.

If you take the tour at Graceland, you can see him on videotape, telling a reporter that he just wants to "hang on to" the house for "as long as I can."

He'd come from nothing with no more than a kid's understanding of the world, but he didn't take his station for granted. He wasn't too good to be Private Elvis.

By the time I understood that Elvis Presley was a real person, somewhere out there in the world, my parents had long ceased to be fans.

I was born while he was in the Army; the only albums of his they ever owned were "Elvis" and "Elvis' Golden Records," the compilation album issued by RCA Victor in March 1958, the month he was inducted into the military. That album is believed to be the first greatest-hits album in rock 'n' roll history, and for the rest of Elvis' life I believed it was the only Elvis album anyone ever needed.

Well, that and "The Sun Sessions," the songs he'd recorded at Memphis' Sun Studios in 1954 and 1955, but they weren't available on a commercially available LP until March 1976.

I probably got an early copy; I was reviewing records then and playing them on a college radio station and the labels were very liberal with review copies. But all the album did was reinforce my feeling that Elvis had betrayed his gift; that he squandered a remarkable voice and feel for main-chance celebrity. When Elvis died, I thought he was a lounge act for bluehairs, a jump-suited clown fooling around on stage. I thought he was artistically bankrupt. I had no empathy for him.

A REAL-LIVE BOY

I don't feel that way anymore, though I can still be harsh in my judgments of the work. But what I understand now is that Elvis was not just the cultural force and the kitschy icon we receive him as, but always and inevitably a real-live boy with inherent limitations and good and bad luck.

He had no roadmap and no pretensions — a performer, not an artist, though he was the creative engine behind some of the most powerful art of the last century. It is not too much to say that Elvis Presley and Sam Phillips, in a little studio in Memphis, started a fire that consumed the world. It is not too much to say that he was the primary conduit through which Black style infiltrated the mainstream.

Elvis was singular; his taste was not immaculate, but it was his own and it was infectious. Whatever else he was, he was original.

That's not to say he wasn't an assimilator and that he didn't appropriate whatever caught his magpie eye; that he didn't cop moves from Jackie Wilson or dye his dirty blond hair black because he thought that would give him a better chance at a sustaining movie career after the rock 'n' roll fad passed.

Had he lived, Elvis Presley would be 88 years old today. Maybe you can imagine he is 88 years old, having lived more years under some alias than he ever did as Elvis. I don't credit those theories, but can't say anything for sure except there was a historic Elvis that will eventually be lost to myth and misremembrance, if that hasn't already happened.

Elvis Presley’s “Elvis” album RIGHT TIME, RIGHT PLACE

Elvis Presley’s “Elvis” album RIGHT TIME, RIGHT PLACE

He came along at the right time in the right place, and it helped that he was pretty. He was there when they started throwing money off the truck. Other people may have had talents just as large, but they weren't there. Billy Bob Thornton says there are people working in factories who can play guitar every bit as well as Jimi Hendrix. But they weren't Jimi Hendrix.

There are people who can sing as well as Elvis — better even. Talent is not scarce, talent abounds. You need more.

John Henry was probably a real person too; there are several places around the country that claim to be the spot where he raced the steam drill. The Big Bend Tunnel in West Virginia, the Lewis Tunnel in Virginia and the Coosa Mountain Tunnel in Alabama have all been put forward as the site.

Historian Scott Reynolds Nelson has asserted that John Henry was a 19-year-old New Jersey man who was convicted of theft in Virginia in 1866. Sentenced to hard labor, he was put to work building the Chesapeake and OhioRailroad.

Nelson says Henry beat the steam drill largely because of the skill of his partner who handled the chisel his hammer struck. The steam drill's chisel often broke and took time to replace. Henry died of silicosis, not from exhaustion.

In "Elvis Presley Blues," Welch sings that Elvis "shook it and he rang like silver/And he shook it and it shined like gold," which is an allusion to several folk songs that describe John Henry's hammer as ringing like silver and gold. Elvis, she notes, was in "long decline," but he still was fighting.

And that he was subject to the same kinds of human worry and wonder that we are all susceptible to, that he wasn't some alien and if he was warped he was warped by forces that were larger and less gentle than himself.

He fought his own steam drill, a fame monster that impinged on his soul and foreclosed his options to such a degree that many of us imagine that he might have wanted to escape from himself.

That he might have wanted more than anything to be ordinary.

Bless our souls, what's wrong with us?

Email: [email protected]