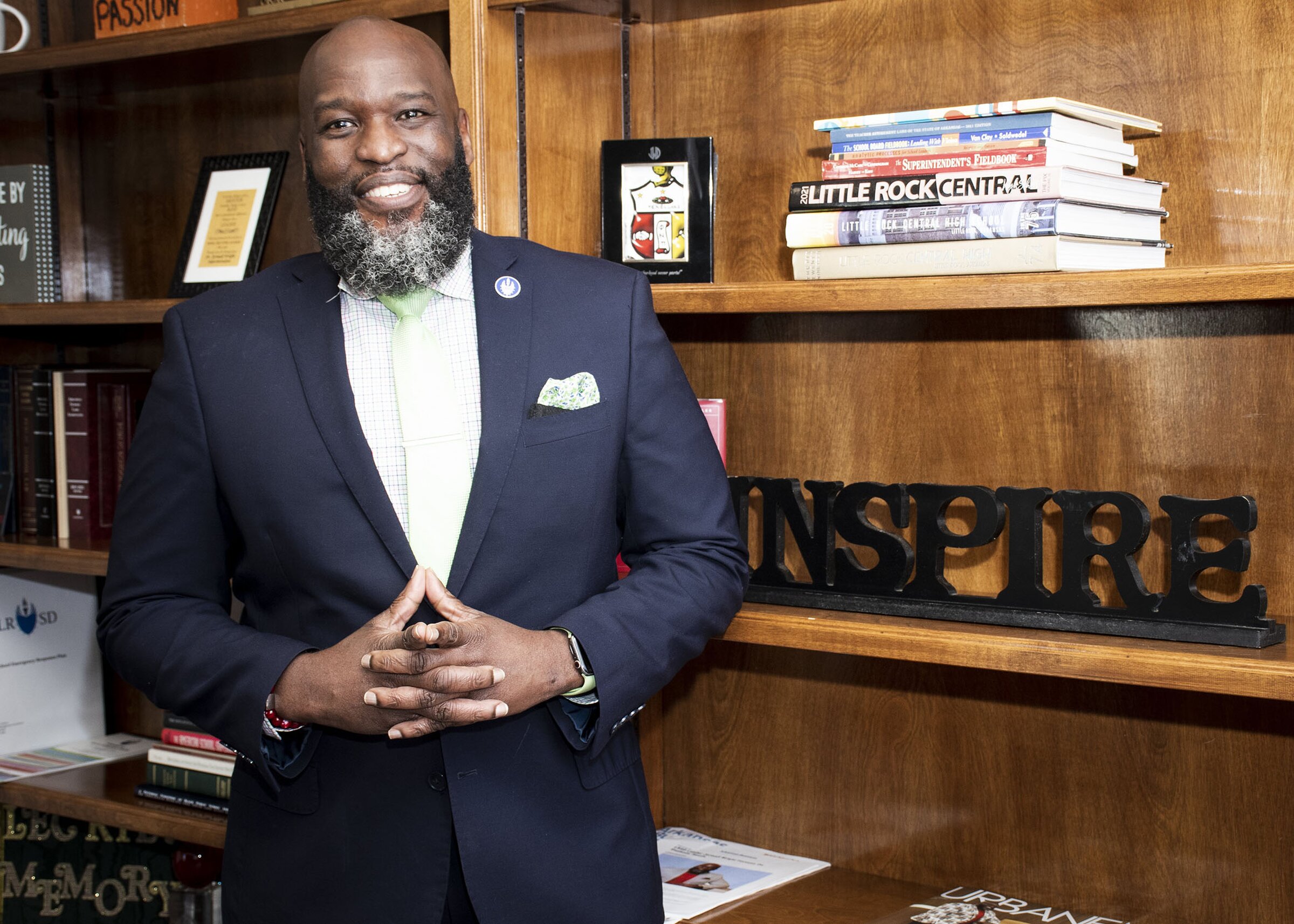

Jermall Wright might not have expected to reach celebrity status as an educator, but he has a hard time going anywhere in Little Rock without being recognized as the Little Rock School District's superintendent.

"It's becoming harder and harder to be anonymous," says Wright, easily recognizable with his well-groomed, full beard and, usually, a pair of Converse, which he owns in seven or eight styles and colors. "It comes with the territory."

Wright, who officially took the helm of the 22,000-student Little Rock School District on July 1, is not entirely at ease with the visibility of the position, preferring that all eyes stay on the work at hand -- improving academic achievement, raising graduation rates, making sure students are safe in their classrooms and the like. But he knows that everyone has an opinion about how those things should be done.

"I chose to come here," says Wright, 47. "I really want to make a difference in a system that may not have been living up to its full potential, and so I am sacrificing a lot, personally, to be here, because I want to see our families and I want to see our community do well."

Wright came to Little Rock by way of the Mississippi Achievement District, made up of schools in Yazoo City and Humphries County and run by the Mississippi State Board of Education since 2019. The Achievement District was slated to be created in 2018, but the board had been unable to hire anyone to lead it until Wright, then chief academic and accountability officer in Birmingham City Schools in Birmingham, Ala., accepted the job of superintendent there in 2019.

The problems facing the Mississippi district were similar to those facing the Little Rock School District, which was taken over by the state in 2015. The state Board of Education gave partial control of the Little Rock district to a newly elected school board in 2019, but did not fully release it from state control until 2021.

The takeovers in both states were linked to test scores, but Wright points out those don't tell the full story.

"I think everybody understands and realizes that you have to have accountability. You have to have ways in which you know how students and schools and districts are performing," he says. "Unfortunately, what came out of the accountability movement was a lot of finger-pointing at teachers, finger-pointing at educators, finger-pointing at parents, and at students, but we didn't dig down deep enough to really identify the fact that there are so many inequities that exist within our society and that play out in different ways."

Factors beyond students' control, including socioeconomic status, race, family makeup and poverty, have been shown to affect their academic performance and deserve far more attention, he explains.

"I hate the finger-pointing, I hate the blame and I hate the fact that we don't take the time to focus on those systemic issues that really drive patterns of socioeconomics in our country and that again play out in things like test scores," he says.

Little Rock Mayor Frank Scott appreciates Wright's continued support of the community schools model, created through a partnership between the city and the district to identify and meet the needs of the most vulnerable students.

"We want to continue to work together to find new opportunities, not only to strengthen that model but to bring forth new works together," says Scott, adding that he and Wright discovered after Wright was hired that they have mutual friends from outside Arkansas. "The main thing is the great relationship that I think is going to push toward more positivity."

Scott anticipates widespread benefits from community schools.

"As we know, many of the [homicide victims] that we've experienced in the last few years are between the ages of 15 and 25, so they're our youth," he says. "That's the reason why the community schools model is critical. As we focus on our youth in those particular schools to ensure that they have appropriate wraparound services needed to achieve in school, it helps us to save a generation and ensure that they're not only being saved but they're thriving."

Wright wants to offer choices for all students.

"I want to provide a path for students to be able to break out of the cycles of poverty or the cycles of whatever generational issues have [affected] them, and the way to do that is by finding adults who believe that kids can learn and kids can achieve at high levels and that kids can be and do whatever they want to do," he says, "and then stack as many of those adults in schools as possible, to be able to provide that ecosystem or that culture within the building to where, no matter what the financial or the socioeconomic status of your family, you can still be great and you can still accomplish great things."

MAKE-BELIEVE TEACHER

Wright does not remember wanting to be anything other than an educator. As a child growing up in Jacksonville, Fla., he used whatever was at hand to create lessons for children in his neighborhood.

"From our church, I would take some of the older supplies and bring them home, and then my mom had a lot of educational-related things in our house as well," he says. "I would use those things to pretend that I was a teacher."

Around seventh grade, his focus turned to student government.

"I just had a great time in high school -- I know this sounds crazy -- working alongside my high school principal a lot, advocating for things for [the] student body, leading a lot of initiatives and programs and activities," he says. "I had a great time as a student putting on programs and activities and so that's kind of what burst my love not just for education, but for really making school an enjoyable place for children."

Wright is the youngest of five siblings, and there are 10 years' difference between him and the sister closest to him in age. His mother was in her 40s when he was born, and he wonders if some people might have mistaken his oldest brother and sister-in-law for his parents.

"I tell people the first superintendent that I knew was my mom. She was the superintendent of Sunday School in our denomination, the Missionary Baptist denomination," says Wright, whose father was a pastor. "I grew up in a home where the majority of my time was actually spent in church or doing church-related activities, and so although my parents were not formal educators, they were educators in terms of church and community."

One of Wright's sisters, Denise Walton, is a specialist in the Duval County Public Schools in Jacksonville. Walton remembers him as an inquisitive child, a sometimes mischievous -- but resourceful -- little brother who borrowed her belongings in hopes of trading them for something he might like more.

"He has a passion for education," she says of him all grown up. "He strives to gather the most information he can to make the best decision as possible for students, for faculty, anyone who's under his care. He wants to bring out the best in those persons. He always has a curiosity, and he's always exploring his environment, I guess looking around to see what he can use to do that."

Wright is a divorced father of three children -- Jaydon Jermall Wright, 21; Trinity Ja'el Wright, 19; and Joshuwa Jermall Wright, 17, all of Jacksonville. Jaydon is a senior at Florida State University, completing his degree online while working full time at Merrill-Lynch, where he completed an internship during his sophomore year. Trinity is completing a cosmetology license during a gap year before college and Joshuwa is a junior in high school.

"He's making more money as a senior in college than I did after 20 years as a teacher," Wright says of his eldest son.

Wright's first education position was as a teacher at the Potter's House Christian Academy in Jacksonville.

"I started out as a fifth-grade teacher, so I was teaching all content areas, although my content knowledge in some areas probably wasn't what it needed to be so I had to learn over time," he says. "I think my classroom was one that every kid in the school wanted to be a part of because it was that noisy classroom where the kids [were] always having fun. I was a fun teacher, but I was also extremely strict."

He embraces that style as an administrator, too.

"It is kind of ironic that when I look at how I am today as a leader, I'm the exact same way. I am very jovial, very friendly and I joke a lot," he says. "But in a split second I will revert back to, 'This work is serious.' I love to have fun, but I also take my role very seriously."

STRUGGLING SCHOOLS, STRUGGLING STUDENTS

Wright later became a principal in Florida's Duval County Public Schools and later in District of Columbia Public Schools. From there, he was hired as instructional superintendent in Denver Public Schools and then assistant superintendent in Philadelphia.

"I would say that I've spent probably 80% of my entire career working either in schools or school districts or in positions that were focused on students or schools that were not making adequate progress," he says. "I've always worked supporting struggling schools or struggling students or struggling systems, per se."

Clara Canty was his supervisor in Washington.

"I would consider him a servant leader," says Canty, who was instructional superintendent while Wright was a principal. She is now retired and working part time as a consultant. "He supported his staff. He had a great relationship with the community, with the parents and the students. He's humorous. He's a funny guy. But he was very data driven. Achievement was first."

Canty also describes Wright as a collaborator.

"I think he's got the Little Rock school system; he's going to do his very best. I think he realizes there are some challenges ahead, but I think he has established partnerships and knows that he cannot do it alone," she says. "He takes interest in what stakeholders want and need and then develops a plan from there."

Retired superintendent Mike Poore worked with Wright as he transitioned to taking over the Little Rock district last summer.

"I'm excited to know that somebody of Jermall's caliber is my [successor]," Poore says. "I think he's got the right heart and the head for this, and I think he's had a pretty good six months. Of course there have been some challenges, but it's not an easy job. I feel like he's coming in and doing the right work."

Their goals are similar but their personalities are opposite -- Poore is an extrovert, Wright a self-proclaimed introvert.

"I really like to remain low-key, which is hard to do in this role," Wright admits. "That is my least favorite thing to do -- the public speaking stuff."

Poore says Wright appears poised to continue work toward career education programs in the district as well as toward improving literacy rates.

"Both of these two topics, interestingly enough, aligned very well with what Gov. [Sarah Huckabee] Sanders is being a proponent of," he says. "The challenge is going to be that a lot of things that go down in the legislative group will [affect] Little Rock in different ways than they will in other parts of the community, so it will be interesting to see how the spring goes for him. That's going to be a place where I think he's going to have to use his voice wisely."

Poore applauds Wright's implementation of various school security measures, including the assignment of student identification badges and the installation of metal detectors at middle and high schools throughout the district this year.

Wright anticipates praise and criticism for most of his decisions, including his plan to create tiered levels of support for schools in need of academic improvement, his intention to reorganize the district administration, his design of a leadership pool from which candidates can be pulled for open positions and his proposal for international recruiting to fill teaching jobs.

He sometimes struggles with how to process all the input.

"I think it would be different if I didn't feel supported by the community at large," he says.

CYBERATTACK

In November, district officials discovered a cyberattack targeting Little Rock schools' staff and students. Wright was driving somewhere around Birmingham on his way to visit family in Florida the Monday before Thanksgiving when he got a phone call letting him know the "threat actors" had named an initial ransom request -- and they wanted an answer before Thanksgiving.

"I think it was probably the loneliest I've ever felt in a position," he says. "I couldn't make any decisions like this on my own, and my board was aware of the issue, but they weren't aware of all the intricate details about everything that happened, and so I can't go to them and say, 'Hey, these folks are asking for this ... .' It was crazy. Thanksgiving was nuts, and I worked every single day, up until Thanksgiving, with our consultants and forensics folks that we hired. People would just not understand how that week was for me."

The district paid the ransom, but the investigation into what information the hackers accessed is still ongoing.

Wright, acknowledging the stress that comes with his job, makes a conscious effort to take an hour each day for a jog or walk, or a trip to the gym.

"And I've got friends and family all over the country, so a couple of times since I got here I've taken a weekend trip, either to Boston to hang out with some old college friends or to D.C. to hang out with some of my folks, so I do find time to get away," he says. "It's just that sometimes I get away and I'm still working."

He constantly assesses and reassesses, not just the work to be done, but also what it takes for him to do it.

"Oftentimes people look at a salary that's attached to a job like this and think that it's about money. And I can tell you there are so many ... easier ways to make what I make here doing something that's less taxing and mentally draining," Wright says. "I just want people to understand and know that I chose to come here because I'm deeply committed to making sure that kids like me are provided access to opportunities that they may not get otherwise."

SELF PORTRAIT

Jermall Wright

• IF I HAD TO EAT THE SAME THING EVERY DAY: I would choose blue crabs.

• THE BEST ADVICE I EVER GOT: Don't ever compromise your core values for anything or anyone, and always treat individuals with dignity and respect.

• IF I HAD TO CHOOSE A DIFFERENT JOB: I probably would have been a professor/administrator in higher education or a historically Black college or a university band director.

• MY KIDS WOULD SAY: I'm cool and young, but they call me lame and old.

• MY MOST PRECIOUS CHILDHOOD MEMORY: Is of my dad taking me and my cousins on various trips throughout Florida. Visiting the Alligator Farm in St. Augustine, Fla., is probably my fondest childhood memory.

• FIVE PEOPLE I WOULD INVITE TO A FANTASY DINNER PARTY: Pope John Paul, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Oprah Winfrey and Gloria Ladson-Billings.

• THE BEST TIME OF DAY FOR ME IS: 4:30 a.m. This is my reflection time, when all is quiet and still.

• I WISH I HAD MORE TIME TO: Spend with and invest in my own children.

• SOMETHING FEW PEOPLE KNOW ABOUT ME: I am an introvert and if I could avoid talking and speaking in front of any kind of audience, I would!

• ONE WORD TO SUM ME UP: Driven