More than half a century has passed, but the memories remain vivid of stops at Caddo Gap with my father.

If it were spring, summer or early fall, he would stop the car as he made his rounds (he sold athletic supplies to high schools, and there was nothing I would rather do than travel with him) and let me wade in the clear waters of the Caddo River. We also would pay a visit to the statue of a Caddo Indian, located a couple of blocks off Arkansas 8 in this small community in the Ouachita Mountains of Montgomery County.

Despite having been dammed near its mouth to form DeGray Lake, the Caddo River is in many ways for the southern half of the state what the Buffalo River is for the northern half. It has never received the publicity of the Buffalo--which some here consider a good thing--but resembles the Buffalo with its spring-fed water and abundant smallmouth bass population.

"Many generations have settled, explored and enjoyed this stream," Brian Westfall writes for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in a short history of the river. "The spring-fed Ouachita Mountain stream offers something for everyone. Visitors to the Caddo can experience diverse recreational opportunities in a safe, easily accessible, natural setting.

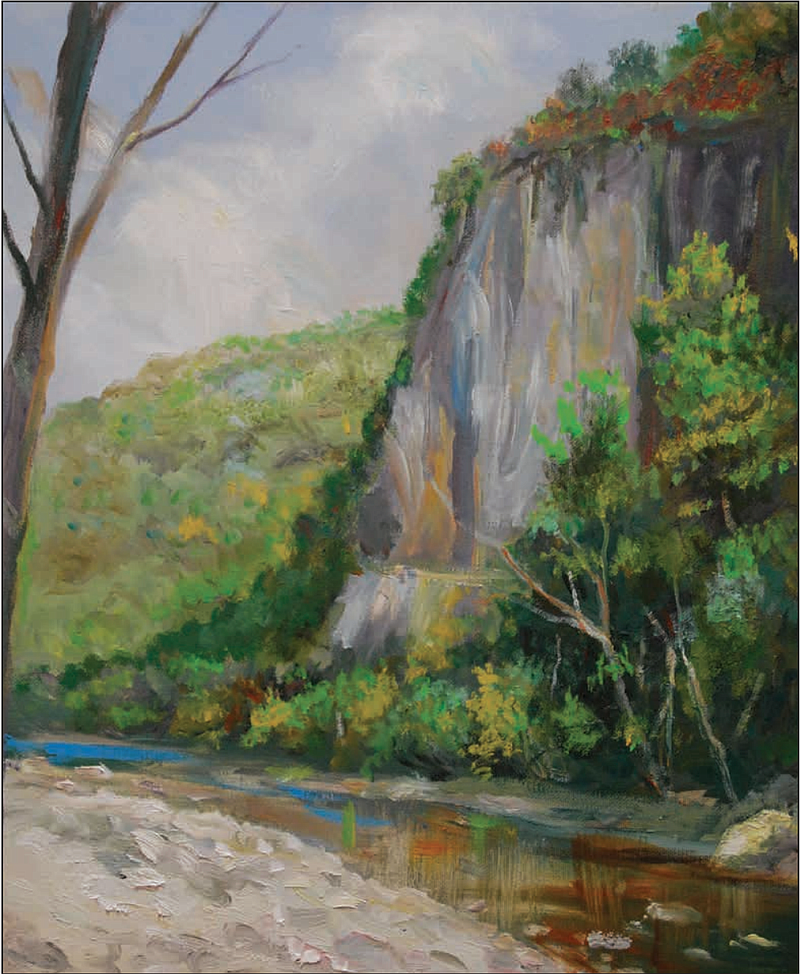

"For centuries, this unique waterway has carved its way through sedimentary rock formations, creating a broad, shallow river valley and leaving miles of gravel along its path. In some places, the nearly vertical beds of sandstone and novaculite create rapids and water gaps."

Much of the land near the river is part of the Ouachita National Forest, which originally was known as Arkansas National Forest. The forest was created by an executive order issued by President Theodore Roosevelt in December 1907. Gifford Pinchot, who headed the U.S. Forest Service at the time, noted that it was the only major shortleaf pine forest under federal government protection.

In 1908, an article in Forestry & Irrigation Magazine praised the people of west Arkansas for their spirit of cooperation and told of benefits gained from the conservation of timber. The 1911 Weeks Law, which authorized federal purchase of forests in the eastern part of the country, was used to enlarge the national forest. During the Great Depression, the federal government bought thousands of acres that had been harvested and never replanted during the period of Arkansas history known as the Big Cut.

Lasting from the 1880s through the 1920s, the Big Cut saw Northern-owned timber companies come to Arkansas and remove virgin timber. It was the cut-out-and-get-out period when only stumps were left behind. Soil erosion followed.

In April 1926, President Calvin Coolidge changed the name to Ouachita National Forest. In December 1930, President Herbert Hoover extended the national forest into eastern Oklahoma. The forest now consists of almost 1.8 million acres in 12 Arkansas counties and two Oklahoma counties.

According to the U.S. Forest Service: "It's the largest and oldest national forest in the South. The forest includes 60 developed recreation areas, six wilderness areas, two national wild and scenic rivers, 700 miles of trails, several scenic byways, special interest (botanical and scenic) areas, historic and prehistoric resources, and habitat for 11 federally listed--and hundreds of other-- plant and animal species.

"It also provides timber and other forest products to the nation, offers hunting and fishing opportunities, and is the source of high-quality drinking water for hundreds of thousands of people in Arkansas and Oklahoma."

During a recent visit to Hochatown, an unincorporated community adjacent to the Ouachita National Forest in southeastern Oklahoma, I saw dozens of homes being built for the thousands of Dallas-Fort Worth area residents who flock there each weekend. A summer weekend can draw as many as 30,000 visitors.

I asked myself what part of Arkansas might be a draw for the DFW crowd and decided on the area along the Caddo River between Norman and Glenwood. It's far more beautiful than Hochatown and still close to Texas. While not wanting the traffic congestion of Hochatown, a smaller infusion of wealthy Texans would bring needed tax dollars to Montgomery County and revitalize places like Norman and Caddo Gap.

"This area has long been popular with wade and float fishermen because it's an ideal smallmouth bass habitat," Westfall writes. "Numerous creeks enter the river along this section. Limestone rock limbs and gravel shoals produce eddies that hold large numbers of smallmouth. ... For the most part, the river corridor is still natural in appearance. Towering sycamore, gum, cottonwood, ash, water and willow oak, and river birch line the banks.

"Even an old logging railroad tram parallels the river and gives it an added flavor. During the summer, cardinal flower, composites and other wildflowers give the river a colorful look. Deer, beaver, river otter, wild turkey, osprey and bald eagles are present."

The most popular section of the river for canoeists is from Caddo Gap to Glenwood in Pike County. This section can be paddled for most of the year.

"The main attraction here is the Caddo Gap, a narrow, boulder-strewn gorge," Westfall writes. "The ancient Caddo River created the gap as it slowly eroded the Arkansas novaculite. Naturally occurring thermal springs rise from the riverbed about 200 yards northwest of the old low-water bridge. The hot springs average 95 degrees and can be felt as the thermal waters rise from the depths into the river.

"For centuries, the Caddo and other tribes were attracted to the springs for religious and medicinal purposes. According to legend, Indians rolled enormous novaculite boulders off the mountan pass onto the Hernando de Soto expedition in the 1540s. According to certain accounts, the de Soto expedition traveled down the Caddo while departing the Ouachita Mountains."

The pedestal of the Indian statue at Caddo Gap claims that de Soto "reached his most westward point in the United States" near here. Historic markers surround the monument.

One reads: "This region was once the home of the Caddo Indians, whose settlements and towns were scattered over what is now southwestern Arkansas, northeastern Texas and northwestern Louisiana. The Caddo River, which flows near this point, and Caddo Gap itself were named for this intelligent and gifted native American people."

Another reads: "In this area in 1541, a Spanish expedition from Florida commanded by Hernando de Soto encountered fierce resistance from the Indians, which they described as the best fighting men they had met. De Soto then turned to the southeast and descended the Caddo and Ouachita rivers into what is now Louisiana, where he died."

The marker was put up by the Arkansas History Commission (now the Arkansas State Archives) in 1936. Modern historians no longer believe that de Soto's expedition fought Native Americans in this area.

Yet another marker reads: "About a mile south of this point is the natural gap, or narrows, of the Caddo River, famed in history and legend. A pioneer road through the gap connected Fort Smith with Old Washington and other points, with a toll bridge spanning the river. The original gap has been widened for a railroad and highway."

A fourth marker reads: "Settled before 1850, the first village of Caddo Gap was located near the natural gap of the Caddo River. The coming of the Gurdon & Fort Smith Railroad in 1907 led to the construction of the present town on what was formerly the Jim Vaught plantation. For several years, Caddo Gap was a popular health resort."

A bronze restoration of the Caddo statue was dedicated by Gov. Bill Clinton in 1980. It replaced the concrete-and-copper original that was brought to Caddo Gap by attorney Osro Cobb. The original statue--the one I would visit with my father--had fallen into disrepair.

Cobb is among the many interesting figures who grew up in this part of Arkansas. He was one of the rare Republicans in the state during the first half of the 20th century, was U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas during the 1957 Little Rock Central High School desegregation crisis and was appointed to the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1966 by Gov. Orval Faubus. Cobb became the first Republican to serve on the court since 1874.

"Cobb was born near Hatton in Polk County in May 1904 to Philander Cobb, a businessman in the timber industry, and Ida Sublette Cobb, a writer, poet, playwright and songwriter," Aaron Rogers writes for the Central Arkansas Library System's Encyclopedia of Arkansas. "He had two brothers. Cobb's family relocated frequently due to his father's business dealings, moving to Womble (now called Norman) and later Caddo Gap, where Cobb and his brothers grew up.

"Cobb often followed his father to work as a child and took an interest in the family business. In the fall of 1920, he entered what's now Henderson State University at Arkadelphia. While in college, Cobb arrived at a conviction that increased political competition from a strong Republican Party would earn Arkansas more attention from presidential candidates during elections and thus improve the state's economic and political fortunes."

Cobb graduated from college in 1925 and ran for the Legislature as a Republican in 1926. He served two terms, representing Montgomery County. Cobb also attended law school in Little Rock and began practicing law in 1929. He ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1936 against Democrat Carl Bailey.

Cobb married oil heiress Audrey Umsted in 1938. He never forgot where he was raised and often came back to Montgomery County.

Montgomery County reached its peak population when Cobb was a boy. There were 12,455 residents in the 1910 census. That dropped to 11,112 by the 1920 census as timber was depleted and sawmills began to shut down.

During the Great Depression, thousands of Montgomery County residents left to find work. That trend continued through the 1940s and 1950s. By the 1960 census, there were just 5,370 residents. Montgomery County had a population of 8,484 in the 2020 census.

"By 1920, Womble (renamed Norman in 1925) had surpassed Mount Ida in population, 420 to 298," Mary Lysobey writes for the Montgomery County Historical Society. "In 1918, the Caddo River Lumber Co. began a survey for building a railroad out of Womble, but it took four years for the 15-mile main line to be completed to the Mauldin logging camp, the county's logging center.

"In 1936, a commissary and post office served incorporated Mauldin's 300 people. In 1937, Mauldin was dismantled and carried off by rail. The lumber company, picking up its tracks as it left, had depleted the virgin timber. This, together with the Great Depression, had a devastating economic impact on the county."

Ultimately, almost 65 percent of the county became part of the Ouachita National Forest as bankrupt farmers and lumber companies gave up their land. That helped protect natural resources, but the lack of private property meant far fewer property taxes to fund schools and government operations. That's why an influx of wealthy Texans--both visitors and retirees--could help the county.

Betting on Montgomery County in a big way are developer Rick Williams and commercial real estate executive Brian Gehrki. They've renovated three historic cabins near Caddo Gap and are renting them to visitors. What are known as the Bean Creek Cabins sit on 495 acres Williams purchased in 2014. Williams is now considering how to further develop and promote the property.

After touring the cabins with Williams and Gehrki, I drive through Caddo Gap, a place that doesn't seem to have changed all that much since those visits with my father five decades ago. The waters of the Caddo River beckon me, just as they did when I was a boy.