Recently, Joe Spivey, one of the trustees of Northwest Arkansas Community College, invited me to be a guest at the Noon Rotary Club meeting. The program was about a black slave who eventually became a prominent figure in the development of Rogers and Northwest Arkansas. I had never heard of this man and so was very interested in the story.

"Rock Van Winkle: Black Builder of Northwest Arkansas" was the program presented by Dr. Christopher J. Huggard and Jerry Harris Moore, both professors at the community college. Together they spent two years researching the story of Rock Van Winkle, and it was featured in the spring 2021 Arkansas Historical Quarterly. Here are excerpts of that story:

Aaron "Rock" Van Winkle parallels the rise of Northwest Arkansas from a frontier society to a modern one. Brought to the area as a child in the 1830s, he had been working as a lumberman in the region for more than two decades by the late 1870s. He had become well known and admired across the rugged Ozarks. Clients in towns all over Northwest Arkansas and into Kansas, Indian Territory (Oklahoma), and Missouri regularly welcomed Van Winkle and his massive deliveries of fine lumber, especially during the unprecedented development after the Civil War. Rock was principal agent of Van Winkle Mills, owned by Peter Van Winkle. He distributed immense quantities of oak, pine, walnut, cherry and hickory lumber hewn by saws housed in a three-story mill in a remote part of eastern Benton County (now Hobbs State Park). Partners in a sawmill empire that earned Peter Van Winkle the title of "timber king," the two men provided materials needed to build hundreds of homes and businesses to all of the chief towns of Northwest Arkansas -- Fayetteville, Bentonville, Shiloh (Springdale), Rogers, Huntsville and Elm Springs. Rock Van Winkle helped Peter's thriving industrial enterprises as a skilled engineer, respected supervisor and trusted confidante. Yet he had spent the first half of his life enslaved.

Aaron Van Winkle was born into slavery in 1829 in Lawrence County, Alabama, and christened "Aaron." He was named for his father, Aaron Vincent, and at the time of Rock's birth, he was the property of Hugh Anderson. In September 1835, Anderson had acquired 600 acres in Washington County and a 600-acre farmstead about eight miles south of Bentonville where young Aaron spent most of his formative years. Hugh Anderson died in 1849, and sometime after that, Aaron became the property of Peter Van Winkle.

Peter owned two slaves in 1850, but he had acquired 12 by the start of the Civil War. Peter Van Winkle was an innovator in all that he did, including breaking sod with plows that he invented to being an expert wagon maker. He was religious and believed in perpetual hard work and profit making. "Only a fool wishes for what he wants; a wise man works for it," he was known to have said.

About 1840, Peter Van Winkle married Temperance Miller, who was 15 years old. Soon after, they started a family on their farm near Fayetteville, and eventually had 12 children. Peter moved his family to Benton County in 1850 and gained a reputation as a wagonmaker, mechanic and sodbuster. He started buying up timberland out near War Eagle and eventually owned many thousands of acres.

The Van Winkles were not the first pioneer milling family in the area. Sylvanus Blackburn, father of J.A.C. Blackburn, had operating in the area since the 1830s. Like Van Winkle, Blackburn had begun modestly with his mill on War Eagle Creek. By the time of the Civil War, Blackburn had 10 slaves sustaining his operations. Together, the Van Winkles and Blackburns, rather than becoming timber industry rivals, developed a lasting business partnership and bond culminating in 1868 with the marriage of Ellen Van Winkle to J.A.C. Blackburn.

By the time of the Civil War, Aaron Van Winkle had earned the nickname "Rock" and was a key figure in the sawmill industry of Northwest Arkansas and the wider Ozark region. His acumen in all phases of sawmilling earned him the title of engineer. Even while being a slave, he held an elite position in the War Eagle community. His world was one of work, service to Peter and his family, and association with elite whites and a workforce of free working-class whites and enslaved blacks.

By 1861, when Arkansas seceded from the Union, Rock and the other slaves had played a central role in Peter Van Winkle's rise to wealth and preeminence. They had labored to build the huge mill complex in Van Winkle Hollow, complete with the centrally located plantation-style home, three-story steam-powered sawmill and gristmill, a blacksmith shop, employees' quarters, a mule paddock, terraced gardens, a barn, stables and other facilities. By the beginning of the war, Peter's estate included 1,370 acres of timber and 12 slaves valued at $9,600.

The pro-Confederate Peter Van Winkle received a $21,000 contract to provide the lumber and part of the labor for the Confederates' sprawling Camp Benjamin at Cross Hollows. The camp was completed by February 1862 with tens of thousands of board feet of planks and other materials. Rock probably played a key role in the production and shipment of the building materials. However, just a few days after completion, the entire complex was burned by the Confederates to keep it out of the hands of the Union Army. Peter Van Winkle did not receive a dime for all of the materials and labor.

The defeat of the Confederate forces at Pea Ridge caused Peter Van Winkle and his entire contingent to flee to safety. The Confederates while retreating from the area were burning everything of value that could be used by the Union Army. Peter took his family and slaves, including Rock and Jane (Rock's future wife), and fled to Texas until the war was over. Rock, like many slaves, took the name of his owner, Van Winkle.

By April 1866, Peter and Rock and their families had returned to the area and began efforts to restart operations. Rock, Jane and most of the former slaves decided to remain as employees with Peter and his family. They built new homes in Van Winkle Hollow with Peter building another plantation style mansion where the first one had stood. Rock and Jane exercised their new rights as free people and married in 1867. They built a new dogtrot style home just south of Peter's mansion and eventually raised 10 children. By 1871, with the supervision of Peter and Rock, the entire milling compound had been rebuilt with the newest technology available. Peter ordered from St. Louis a large 150 horsepower steam engine, three 24 foot boilers and a huge 20,000 pound, 24-foot flywheel.

The new mill, with Rock as the foreman, could produce up to 20,000 board feet of lumber a day. By 1880, the mill included planers, a shingle machine, a flour mill, and a sash, door, and blind factory. The complex shipped up to 150 wagonloads of materials a day and employed 50 men. Rock was a principal player in the enterprise and delivered big loads of lumber to Fayetteville to build the new state university (Old Main), the Van Winkle Hotel, and many other buildings. Rock prospered as Peter's trusted agent. White Van Winkle lore claimed that Peter and Rock were inseparable, and Rock was indispensable to Peter. Peter respected Rock and viewed him as a partner as well as family.

By the 1880s, Rock owned as many as nine cattle, 25 hogs, two mules, two horses and two carriages. In 1880, Rock and Jane purchased an 80-acre farmstead for $400, a lot of money at the time.

About 1880, Peter and Temperance Van Winkle moved their family and the black Van Winkles from Van Winkle Hollow into the Van Winkle Hotel in Fayetteville. The newly constructed luxury three-story hotel symbolized their rise to the top of the social structure in Northwest Arkansas. However, Peter died suddenly on Feb. 10, 1882.

After Peter's death, Rock and Jane continued to live in the hollow, and he was an agent for Van Winkle Mills until 1884, when the entire Van Winkle empire was acquired by Peter's son-in-law, J.A.C. Blackburn. Rock bought an 80-acre farm at Osage Mills and farmed, cut timber, and owned a monument (gravestone) company. By 1898, Rock, in his late 60s, bought a 20-acre plot in western Bentonville for $1,000.

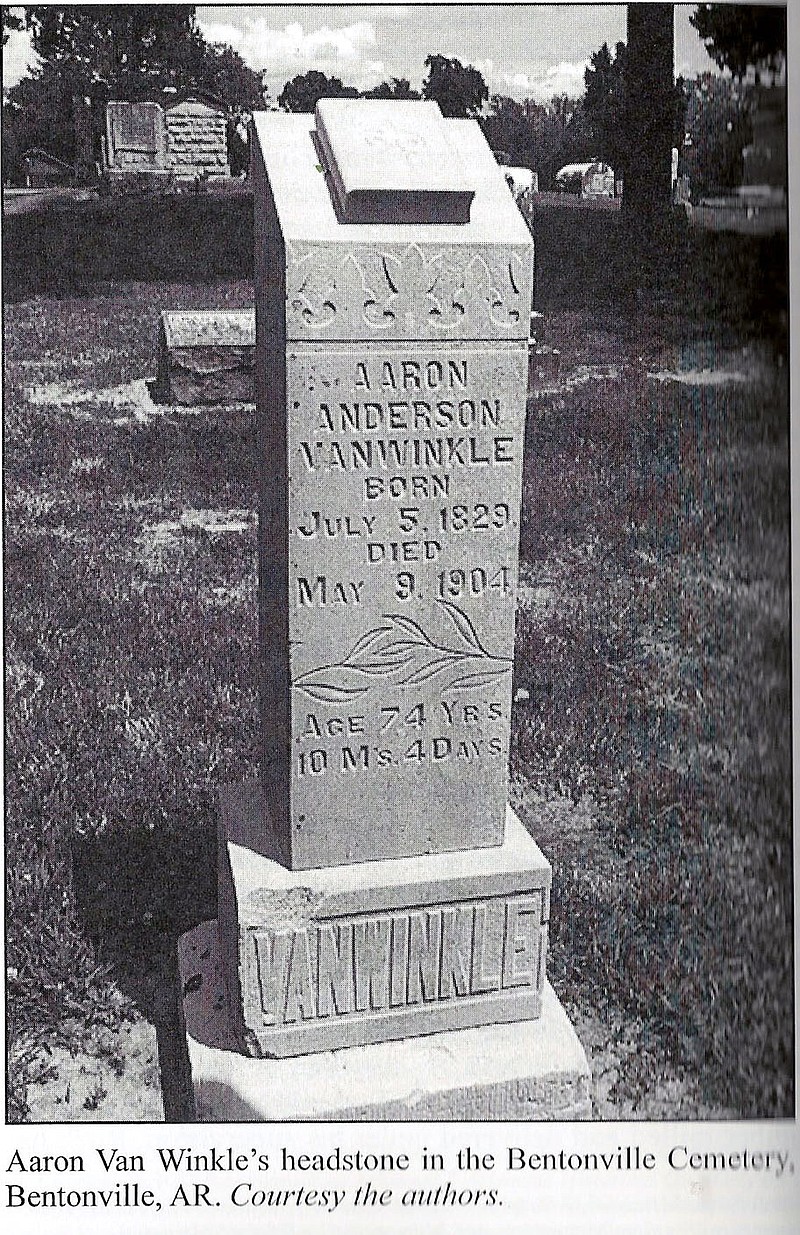

Aaron "Rock" Van Winkle died on May 9, 1904. A large congregation of white and black mourners attended the funeral to pay their respects to this remarkable man. Rock's family invited J.A.C. Blackburn to give the eulogy. "Uncle Rock was known for his honesty, kindness and humbleness. He was one of the best men that I have ever known. If everybody, both black and white, were as honest and trustworthy as Uncle Aaron Van Winkle, this would be a much better world."

Rock Van Winkle was born a slave and never learned to read or write. He was handicapped by living in a racist society that was 96% white, yet he succeeded, earned the respect of all that knew him, and contributed much to the development of Northwest Arkansas.