"Relationships between women don't have solid rules like those between men." — Elena Ferrante to Vogue magazine in 2014

No one knows who Elena Ferrante really is — the author's identity is a secret.

Normally when I hear something like this, my reaction is muted. I understand why a writer might not want to become a celebrity, but also suspect someone is engaged in imagesmithing. You can forge a brand from being reclusive and mysterious; while I suppose artists have the right to market themselves however they see fit — and understand that sometimes the image is the art — I don't feel compelled to care much about these funny games.

But you might remember a few years ago when it was widely rumored that Ferrante, author of the bestsellers "My Brilliant Friend" and "The Lost Daughter," was actually a man who had chosen to write as a woman. This vaguely misogynistic school of thought took a hit in 2016 when an Italian journalist named Claudio Gatti alleged that Ferrante was Anita Raja, a woman who works translating German books into Italian.

Gatti arrived at this conclusion through good old journalistic legwork; an anonymous source provided him with financial documents that showed Raja had received payments from Ferrante's publisher consistent with the performance of Ferrante's novels. He followed the money.

Then in 2018, Ferrante scholars — they apparently exist — alleged that they had, through stylometric analysis, determined that Ferrante's novels were in fact written by prolific Italian novelist Domenico Starnone.

Stylometry is the statistical analysis of a writer's style via quantifiable factors, such as sentence length, vocabulary diversity, frequency of word usage, etc. I read a Massachusetts Institute of Technology paper about the limitations of stylometric analysis and learned that while it can be highly accurate in determining the provenance, most experts consider it inconclusive unless it's supported by other evidence.

If Starnone happened to be married to Raja, then you'd have both the stylometric analysis and circumstantial evidence that Starnone had been indirectly compensated for the novels. Then maybe you could conclude that Starnone was the author of the Ferrante books.

Well, Starnone is married to Raja, who had a freelance relationship with small publishing house Edizioni E/O, which has published Ferrante's books from the beginning. Starnone has also collaborated with E/O on a couple of nonfiction projects, while his fiction was published by the large Italian publishing concern Feltrinelli.

There has been some pushback on the notion that Starnone = Ferrante. Some Ferrante fans can't believe any man could write with such sensitivity about female friendship. Others feel "cheated" that Ferrante has been "exposed" as male. Alternate theories have been offered: Maybe Raja is the writer in the family, and the author of those novels published under Starnone's name.

By way of full disclosure, I'm a bit of a Ferrante skeptic. I've never read "My Brilliant Friend" or its three sequels that make up Ferrante's "Neapolitan Quartet," though I enjoyed the soapy HBO series that was made from it. I did read "The Lost Daughter." I think Maggie Gyllenhaal did a remarkable job of adapting the book to the screen and that her movie is better — more subtle, more evocative — than the book, which was just OK. But I was reading the English translation of the novel, not the original Italian.

The most persuasive piece I've seen on the question was Elisa Sotgiu's essay "Have Italian Scholars Figured Out the Identity of Elena Ferrante?" published on the Lit Hub website in 2021. The TLDR (too long; didn't read) gist of the story is that while Sotgiu admits she doesn't want Starnone to have written the Ferrante books ("my first impulse was to push that information aside, not talk about it, and not think about it too much, either," she writes), she concludes that it's highly probable that Starnone wrote the books, possibly in collaboration with Raja.

And that she was OK with it — because "Elena Ferrante is still a pleasure to read."

■ ■ ■

A writer ought to be able to write in any voice they can imagine. Is anyone seriously going to argue that Tolstoy and Flaubert couldn't write credible female characters?

But just because you have permission to try something doesn't mean you're going to do it well. In her essay, Sotgiu perceptively notes that Starnone's style and preoccupations don't change depending on whether he's writing as Ferrante or under his own name — his female characters are pretty much the same as his male characters. Maybe that's the trick. Just explore human occupations and obsessions and switch the pronouns around as necessary.

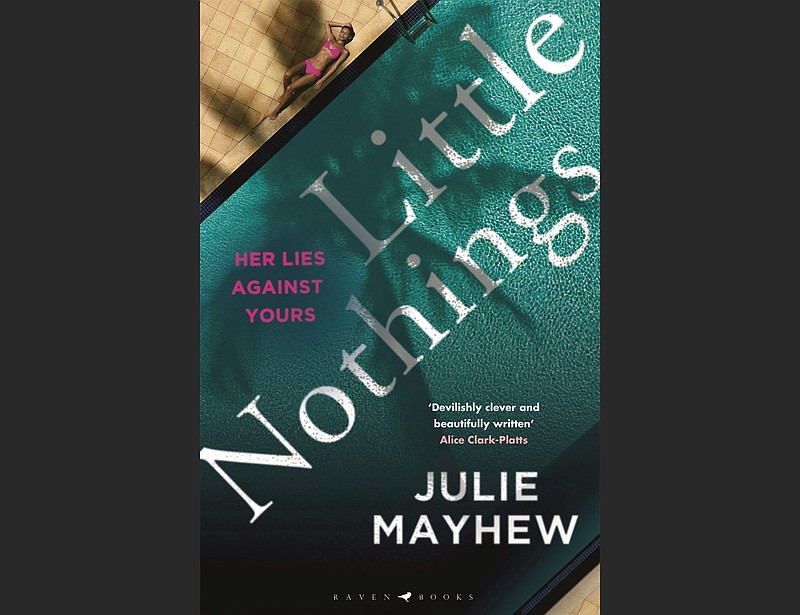

I thought about this while reading Julie Mayhew's page-turner of a novel about toxic female friendship, "Little Nothings" (Bloomsbury, $26). It is very much a sleek and summer read sort of book, more a dark comedy than full-on horror show about an insecure young wife and mother, Liv, who bonds with two other similarly situated young moms, Beth and Binnie.

Soon they're joined by wealthy, ambitious Ange, who takes over as the group's captain, leading them on adventures alcoholic and consumeristic, pushing the limits of Liv's economic bandwidth.

When Ange suggests the four couples and their kids head to an exclusive resort in Corfu for three weeks, Liv is unable to decline the invitation, despite the financial strain and the petty passive-aggressive needling of Ange (who has obviously scented Liv's deep-seated social insecurity).

Mayhew, who has acted, directed and worked in radio, provides the book with a palpable tension that reminds me of the lavish HBO series (based on Liane Moriarty's bestseller "Big Little Lies") and Mary McCarthy's 1963 novel "The Group," which chronicled the post-graduate lives of a clique of Vassar girls through the 1930s. She writes relatable, credible characters, rarely defaults to cliche, and has interesting thoughts about class structures and socioeconomic realities along with her clear-eyed critique of the complex and dynamics that exist between, well, human beings.

It's a highly enjoyable novel that ought not be ghetto-ized as a beach book — and certainly not as chick lit.

Email: [email protected]